Dr Jane Goodall is on a mission – the same one that has propelled her around the globe for the best part of six decades. But she has a renewed sense of urgency, because not only is the planet's time running out, so too, is hers.

She is, after all, "jolly nearly 86". But it's not death that scares Goodall: she says dying is her "next big adventure", and she'd rather people ask about death than about slowing down, which she has long refused to do. It's inaction that scares her. And apathy. And the knowledge that "the most intellectual creature that ever walked the planet is destroying its only home".

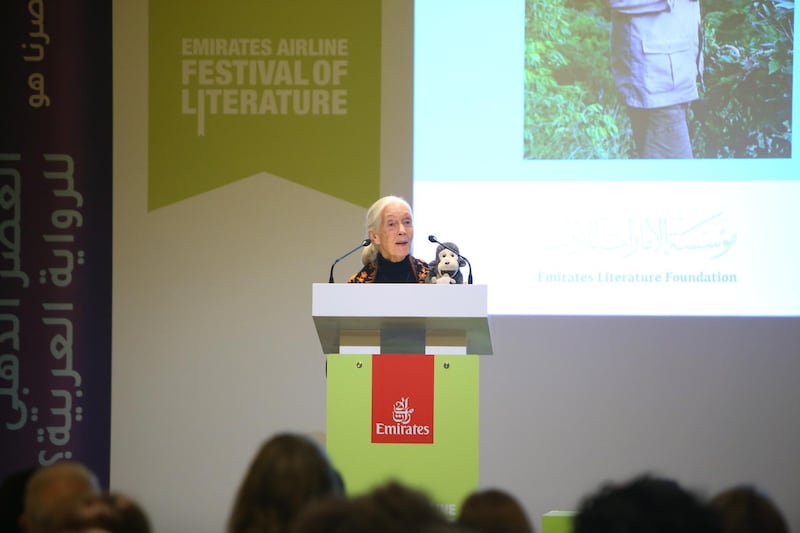

That isn't to say she doesn't care about her message, though. She does, deeply, but how many other ways are there to articulate something she has been repeating for 30 years? Speaking to Goodall ahead of her curtain-raising address at the Emirates Airline Festival of Literature, was almost the same as watching her on stage. She commands attention with the same reserved, yet powerful aura whether she's in a room with one or 100 people. And as I later discover, her responses to interview questions are often word-for-word lifted from the speech she is about to give.

Goodall doesn't necessarily want to be doing interviews after arriving into Dubai at 3am in the morning. But she does, for the same reason she always has: the more people who hear her message, the more there are to share it, even long after she has gone. We are simply her vessels.

“When I was 10, everybody laughed at me because I wanted to go to Africa and live with wild animals,” Goodall recalls wistfully. “And they said how can you, you don’t have money and World War Two is raging and you’re just a girl. Mum said, 'if you want something like this, you’re going to have to work really hard and take every opportunity, don’t give up'. I just wish Mum was alive to know how many people have said or written ‘because you taught me, because you did it, I can do it too’.”

Goodall has been travelling non-stop since 1986

For decades Goodall has rushed from country to country, insisting people wise up to climate change among as many willing ears as she can. Since 1986, she's never spent more than three consecutive weeks in one place.

But anyone who has met Goodall knows that she is perhaps as sharp as she was six decades ago when she lived alongside the chimpanzees in Gombe, now Tanzania, and made the ground-breaking observations that upended modern science and catapulted her to stardom.

She didn't miss a beat as she delivered a 45-minute lecture without notes, to a crowd full of adoring fans in the middle of the Middle East, nor did she bat an eyelid as she directed a photographer to move to a different vantage point, to frame their shot better, before telling a reporter (me) to shift in their seat until they're as close to her as she wanted them to be.

There was an 85-year-old woman who had arrived into Dubai barely nine hours prior, commanding and reorganising the room better than anyone else inside it. “I’ve been interviewed so many times,” she said, a glimmer in her eye, “I know all this”. And now, she said – in the same matter-of-fact tone she employs whether she is speaking to wayward reporters, world leaders or an auditorium full of adoring fans – we may "begin".

With a science and conservation career that has captivated the world since its inception in the forests of Tanzania in 1960, Goodall has yet to sit on her laurels to bask in her own achievements. In fact, every new achievement seems to be even more incentive for her to do more, to try harder.

Goodall's foray into the public consciousness is well-known: the story of a young Englishwoman who saved up all her money for a boat trip to Africa, to live among and study chimpanzees. There were many reasons to go, mostly a deep-rooted love for animals, but she says, perhaps the last straw might have been reading Edgar Rice Burroughs' Tarzan. "I fell passionately in love with that glorious man of the jungle and what did he do? He married the wrong Jane."

Going from living with chimpanzees to trying to save the planet was not 'a conscious decision'

While in Tanzania, Goodall defied critics of her gender, youth and non-scientific background. All her waking hours were spent observing the chimps through binoculars, attempting to inch gradually closer (“they usually took one look at this peculiar white ape and ran away”).

Towards the end of a six-month study grant and with little else to show for her time, Goodall made several phenomenal breakthroughs: she observed a chimp gnawing on a dead animal, which contradicted popular belief that these animals didn't eat meat. That same chimp, which Goodall had nicknamed David Greybeard for his white goatee, was then observed using twigs and grass to fossick in a termite mound for food. Until that time, tool-making and tool use were things only humans were believed capable of. The discovery, alongside a 1965 film entitled Miss Goodall and the Wild Chimpanzees, made Goodall famous.

But it wasn't until 1986, at a conference in America that looked at chimp behaviour in different environments, that her scope widened even further. “We had a session on conservation and it was shocking. Right across Africa forests were going, chimp numbers were going, chimps were being caught in snares, people were moving deeper into the forest, taking disease with them ... it was a shock and I couldn’t sleep after seeing our closest relatives, highly social beings, in [small] cages alone and surrounded by metal bars,” Goodall recalls.

“I went to the conference as a scientist and I left as an activist.”

Goodall on Trump, Greta Thunberg and being misquoted at Davos

There are several methods of tackling climate change, she says, and most involve using our own intellect for good. “We need to eradicate poverty – if we can’t do that, we can’t save the environment, because if you’re really poor you’ll cut down the last tree to grow food. You’ll fish the last fish to try and feed your family. We have to alleviate poverty on the one hand, and cut down on this unsustainable lifestyle. And then there’s the human population. Those are things you can’t argue with,” she says, before adding, “you can misquote what I’ve said about population and people do, probably on purpose.”

“There are 7.2 billion people on the planet today, and they say there are going to be 9.7 billion by 2050. That’s just sheer maths and all you’re saying is what can nature do?"

Goodall is referring to her recent comments, about overpopulation of the Earth, made in Davos at the World Economic Forum last week. Several criticisms of her stance appeared in mainstream media, saying she was oversimplifying the problem. Goodall contemplated writing something to make her position on the matter clear, but opted instead to simply “ignore it”.

“And the criticism that it’s pointing a finger at the developing world, well that’s not true. One child growing up say in Dubai or Abu Dhabi in an affluent family will use at least six if not 10 times more natural resources than an African child. [Overpopulation] just underlies all of the other things that have gone wrong, it just makes the other things worse.”

Goodall still believes in a place for Davos in the global climate fight. She "wouldn't go if I didn't believe we could [achieve change]". This year was particularly heartening, she says, because climate change was at the top of the agenda. She also got to announce her tree-planting initiative, the one trillion tree challenge, which even US President Donald Trump committed to. She also got to observe the momentum with which young people, such as 17-year-old eco-activist Greta Thunberg, are gathering as they champion the cause.

Of Trump, she's made her position very clear. When asked during her speech who she looks to as an influential voice, she says: "I want to answer that another way and say that one person I would not listen to is Donald Trump." In 2017, she compared his behaviour to that of a chimpanzee. Of Thunberg, though, she is hopeful the young Swede will raise even more awareness of the cause. Hope, and young people, are especially important to her right now.

Goodall is hopeful for the UAE's ambitions, and returns here each year

Goodall founded her Roots and Shoots programme in 1991 to bring together youth to work on conservation and humanitarian issues. "So many young people had told me they don't have hope for the future. They were depressed and they were angry – but most of all they were apathetic and not seeming to care, because [they said] you've compromised our future and there's nothing we can do about it. But I think there is."

Roots and Shoots has existed in the UAE for the past seven years. Goodall visits every year to check in on progress. She's impressed with conservation efforts here – about progress in harnessing energy from solar, wind and tide, and the reintroduction of the Arabian oryx to the wild.

“The children are very passionate just like they are everywhere, once we listen to them and empower them to take action. That’s very encouraging.

“As I’m travelling across the world, yes I learn about all the awful things happening, but I meet so many incredible people doing amazing projects and there is a whole new attitude towards the climate, towards saving the forest. People understand at least, and they’re beginning to be brave enough to take action.”

That action doesn't need to be overt activism. It can be shopping ethically and eating less meat, she adds.

Why Goodall believes in veganism

Goodall herself is now vegan, though reverts to vegetarianism when she’s travelling so as “not to be a burden” on those she’s staying with. She’ll also pack a nut butter or a non-dairy creamer to travel with.

She is also deeply opposed to factory farms, labelling them "concentration camps", another comment that's won her criticism in the past. "When I first mentioned that, though, someone said you're comparing animals to Jews. Well, no, I'm not. Luckily a concentration camp survivor wrote about factory farms and called it The Eternal Treblinka. There's always people who want to criticise everything".

Essentially, however, she believes the onus needs to be on the consumer, too. Goodall came under fire when oil and gas company Conoco funded the building of her sanctuary in the Congo. She believes she was lampooned for hypocrisy, "or something like that". But, she reasoned, they were trying to be environmentally concerned.

“I’m using their products, I’m flying and driving. They’re trying to do right, the best thing for me is to try and help them to do better, to support them. And at the same time they can feel better by giving money to us to help the chimps,” she says. “We always tend to blame the producer or a certain company because it’s harming the environment but you’re still buying their products. So the consumer has a role to play here, too.”

Goodall will never be done, but death does not scare her

Hundreds queued for an hour to hear her speak in Dubai, and they sat entranced, listening intently as she introduced the crowd to the stuffed toys she always travels with; each a highly intelligent animal. There's Ratty the rat, Piglet the pig, Octavia the octopus, there's Cow, and then there's Mister H, a stuffed monkey, given to her by a blind magician. He's been with her for 29 years and has been to 65 countries, she tells the audience.

At the end of her 45-minute speech, Goodall receives a standing ovation, as she often does. People wiped away tears as they clapped. More children than adults asked questions afterwards, which she was visibly heartened by. But before she left the stage, Goodall reached back for the microphone: “Thank you so much for coming,” she said, over the applause, “It’s you that gives me the courage and inspiration to carry on.”

This is another clear indicator that Goodall will simply never be finished. Perhaps that is why she has such peaceful acceptance when she speaks of dying. “A thing that’s kind of fun is when people say ‘What’s your next big adventure?’, which is dying,” she tells me calmly. “You either die and it’s finished, or you die and it’s something. In which case that’s the best adventure I can imagine. What is the something? Well, the best scientific minds on the planet now have agreed there is intelligence beyond the universe.”

As the hundreds of people trickled out of the auditorium, some still visibly emotional, they spoke to each other animatedly. We lined up to have our books signed. We texted our friends and family about what we'd heard. We posted on social media.

Her audience in Dubai became Goodall's vessels, spreading her message across the UAE, and across the world. And that message, at its core, is actually quite simple. "Every day, everyone makes an impact on the planet and we get to choose what kind of impact we make. When billions of people start making ethical choices each day we start to move towards an ethical world.

“If we don’t change, then the future is very grim and bleak.”