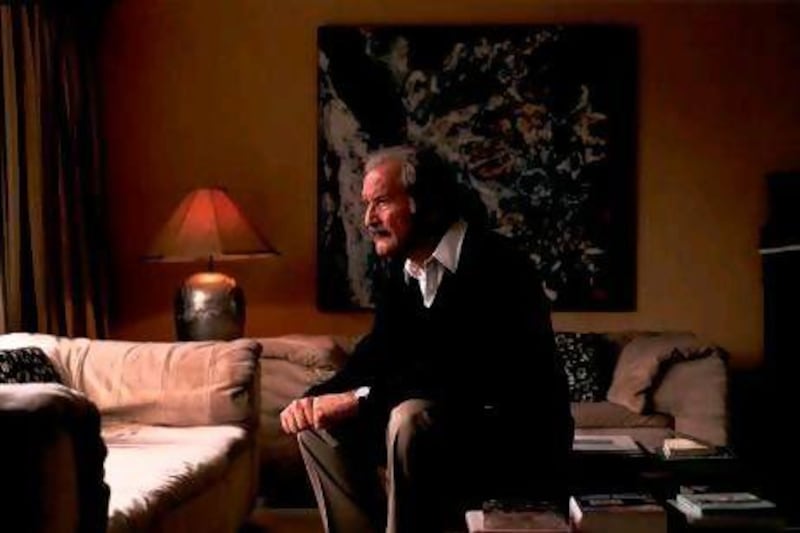

On May 15, Carlos Fuentes died of a massive haemorrhage at 83 years of age. He was without a doubt the most respected, famous and decorated Mexican author of his generation. Mexico's president Felipe Calderón commemorated his passing, obituaries were written in newspapers spanning the globe, and the author was accorded a state funeral in the Mexico City that he had evoked like no other Mexican of his era.

Fuentes is commonly placed alongside Gabriel García Márquez, Julio Cortázar and Mario Vargas Llosa as the co-creators of magical realist writing. It says something about Fuentes' range and the impact that his work has had that his early experimental novel The Death of Artemio Cruz is now a widely read classic of Mexican literature, while others of his books - like Terra Nostra and Christopher Unborn (the latter of which is narrated by a foetus) - are still considered experimental reads and are published by the avant-garde Dalkey Archive Press. Fuentes found new forms to chronicle the mythic foundations of the Mexican nation, and at the same time he mythologised the story of that country's tumultuous 20th-century history, as it modernised and slowly became a democracy.

The latest of his books to make its way into English translation is 2004's Vlad, written when the author was well into his 70s. As the title implies, this slim, quick novella is about vampires: Vlad the Impaler, the historical inspiration for Bram Stoker's Count Dracula, is undead and has come to present-day Mexico City. He has bought an estate that he is outfitting to obscure purposes. Yves Navarro, our narrator, has been assigned as his lawyer to help the transaction, and Yves' wife, Asunción, will be his real estate broker. Needless to say, they will be in for more than a business transaction.

Vlad's identity as both a vampire and the historical Vlad the Impaler are only revealed two-thirds of the way through the story, but it is highly doubtful that the revelations will come as a surprise to any reader. Titling a book Vlad is a gigantic tip-off, and Fuentes gives more than enough hints along the way - in fact, maybe too many. Fuentes hits all the familiar vampire tropes (Vlad has no reflective surfaces in his house, and he has all the windows bricked up), but it's unclear why, or if, Fuentes is attempting to build up the suspense. We're obviously aware that Navarro is dealing with a bloodthirsty vampire; moreover, it's unbelievable that the possibility doesn't occur to Navarro. The suspense serves no narrative purpose, and nor does it serve a thematic purpose: Fuentes doesn't seem interested in subverting the conventions of the genre.

If the vampire side of this story comes off as unnecessarily formulaic in the opening stages, the other side of the story, Navarro's marriage, holds more interest. Navarro and his wife have spectacular sex every night, and they share an hour-long, sumptuous breakfast every morning before work. They have a beautiful young daughter, whom they adore. It would seem they are a perfectly matched couple, right down to their complementary appearances: "Asunción is my reverse image. Her hair is long, straight, and dark. My hair is short, curly, and chestnut-brown. Her skin is white and soft; her body, curvaceous. My skin color is cinnamon, and I am trim. Her eyes are pitch black. Mine are blue-green. In her thirties, Asunción preserves the dark and youthful luster of her hair. In my forties, I have premature grays."

The only thing upsetting their domestic tranquillity is the memory of their son, Didier, who was carried out to sea by a wave when he was 12 years old. Navarro and Asunción are clearly meant to be archetypes: the blissful couple who have never been forced to seriously consider the foundations of their love. We are immediately aware that Fuentes is telling a fable of sorts, and the author artfully implies that the other shoe will eventually drop on their domestic tranquillity.

As befits a fable-like story, Vlad's short plot moves in a very schematic way: first the mystery is established, then the sudden realisation and catastrophe that we knew was coming occurs, and finally there is the concluding showdown and denouement. The first and second parts of Vlad's plot feel very pro forma, as though Fuentes is setting us up for a punchline and must get through all this front matter before hitting us with the really surprising stuff. This puts much responsibility on the book's final third to deliver, which it does with partial success.

On the most basic level, Vlad is a novel about the seductions of youth, an interesting topic for a writer who was nearly 80 years old. Youth, in Fuentes' telling, is a quantity that requires more and more violence to sustain as one ages. It seems that in Vlad's world some people will do anything to retain their youth: for instance, a character who is complicit in the betrayal of Navarro pleads for pardon with the rationale, "He [Vlad] promised me eternal youth, immortality". Vlad is the novella's embodiment of eternal youth, and Fuentes tells us of the ruthlessness required to sustain it. One character says of Vlad's immortality: "Strength alone sustains power, and power requires the strength of cruelty." Vlad's vampiric youth is only maintained at the pain of destroying lives, stealing lovers, and drinking the blood of his victims.

Vlad also delves into the metonymic relationship of love to youth, how each concept can stand in for the other, as they do frequently in the book. As Vlad's third act mounts towards crisis, Navarro reflects on the central role his wife is now playing in events, thinking: "This is the greatest moment of our love." What he's referring to here is the choice that must be made: youth and new love, or age and established love. The choice is the book's most fraught, and it is only fully answered in Vlad's final pages.

As the climax approaches, Navarro ponders: "Is the greatest moment of love … a moment of sadness, uncertainty, and loss? Or rather do we feel love at its most intense when it is right in front of our faces and thus less prone to be sacrificed to the foolishness of jealousy, of routine, of disrespect, or of negligence?" At its most interesting, this is the question that Vlad considers.

Fuentes' book can at times be an interesting ode to love and youth, but it feels rather small. The questions that Fuentes poses in Vlad could have been more concisely and more effectively stated in a short story than in a novella. Too much of the machinery of the book feels as though it is mere window-dressing: atmospheric but ultimately unnecessary pieces that leave no discernible trace in a reader's mind.

Moreover, given Vlad's very schematic use of the familiar vampire tale, the book holds few surprises until the very end. Too many of the would-be revelations encountered throughout feel like nothing more than dutifully checked-off items from the vampire itinerary, and the irony Fuentes at times employs here never becomes rich enough to permit a deconstruction of the genre.

Vlad comes from Fuentes' 2004 collection Inquieta Compañía, which contains five other stories that explore other paranormal phenomena, such as witches and angels. Perhaps in that context Vlad would feel like a more fulfilling work, but alone it is too weak to survive.

Later this year, the Dalkey Archive Press (which publishes Vlad) will be bringing out Fuentes' Adam in Eden, originally published in 2009 and dealing with the traffic in narcotics through Mexico. This sounds like a more promising direction for the aged Fuentes.

Fortunately, Fuentes was nothing if not prolific, and the master's backlist still contains many entities that have yet to reach the English language. There are undoubtedly gems in there, and it is to be hoped that presses like the Dalkey Archive will continue to mine this backlist for them. With an author of Fuentes' stature, there can be no reason not to.

Scott Esposito is the author of The End of Oulipo? An Attempt to Exhaust a Literary Movement, forthcoming from Zero Books.