Taxi

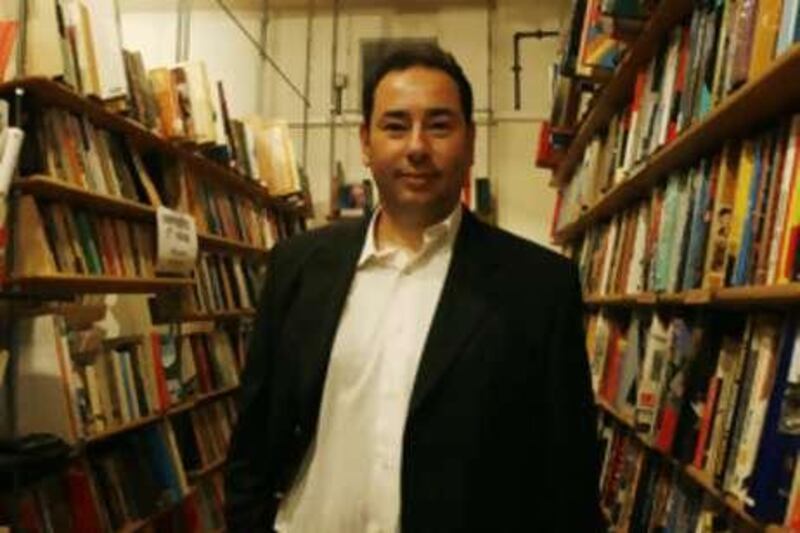

Khaled Al Khamissi

Translated by Jonathan Wright

Aflame Books

Dh58

It is easy to forget that Cairo used to pride itself on being "Mother of the World." Many years have passed since Egypt was a world leader in any field, and it has even lost its paramount status in the political and economic hierarchy of the Arabs. But one part of the economy seems to be flourishing: book sales. Following the success of The Yacoubian Building - Alaa al Aswany's melodramatic portrait of Egyptian society, which became a worldwide best-seller - Cairo has now become hot with western publishers.

The latest Egyptian book to hit the western market is Taxi. Its author, Khaled al Khamissi, has taken the most tired and hackneyed of journalistic clichés - the snatched interview with the taxi driver - and turned it into a best-seller. While any foreign correspondent who admits to getting all his information from a taxi driver would be fired on the spot, Khamissi has sold 60,000 copies in Arabic, and within a year of its original publication, his book has been translated into English.

The book consists of 58 conversations with taxi drivers - short and punchy, with the careless intimacy that comes from talking to a stranger you know you will never meet again. It all happens between April 2005 and March 2006, but it really could be happening now: the main theme - that many in Egypt can barely afford bread - has been played out in riots in the Delta earlier this month over the rising price of food.

Khamissi - a political scientist by training who makes his living from film and television production - has taken a snapshot of Egypt with pinpoint sharpness. The portrait is so real that you understand the inchoate rage of the poor mass of Egyptians, struggling to survive in a world where the dice are loaded in favour of the rich, the corrupt and the criminal. But Khamissi maintains his conversations are not actually real. "I didn't record anything or write it down. This book is fiction," he insists. Interviewed at the London Book Fair, he was adamant that the book was not a work of social science or - for all its immediacy - of journalism. The conversations are composites focused on the character of the Cairo taxi driver - "a dramatic personality, who spends all his time on the street, who is always on the move and meeting all kinds of people from all social levels.

"I wanted to tell the stories of ordinary people. Certainly these stories express the nature of Egyptian society, and you can take what you want from them. But this is not a work of political science." But for all his insistence that the stories are fictionalised, the fact is the Egyptians see them as real - and so will the western reader. Khamissi clearly revels in this ambiguity. He told a BBC radio reporter last year that while the stories were fictional, they were also "100 per cent real" - and invited her to meet one of the taxi drivers who then proceeded to tell his story, exactly as related in the book.

The author is having his cake and eating it. But it is no sin to pass fact off as fiction. Indeed, in a tightly policed state such as Egypt, writers need a little space of ambiguity to manoeuvre in. One of the joys of the book is how the author teases the reader about self-censorship in the Arab world, revealing that he had to leave out the best jokes in order to stay out of prison. When one taxi driver says of the Cairo police: "There's not one of those ******** who doesn't take bribes or steal," Khamissi adds a footnote: "Some people advised me to write that some of them take bribes rather than all of them, but I didn't take their advice."

Khamissi said he had cast around for a long time to find a way to portray the Cairo poor. After more than a quarter of a century of Mubarak's stagnation, Egypt had become a squeezed-out lemon, and many writers felt empty inside as well. They were unsure how to reach their readers or do anything to help their country out of its despair. Eventually he hit on the winning formula: a sort of fiction with a documentary edge, written in the idiom of the street - "a blunt, vital and honest language quite different from the language of salons and seminars that we are used to."

The Egyptian taxi driver is a world away from the middle class London cabbie jealously protecting his monopoly, or the thrusting new immigrant behind the wheel of a yellow cab in New York. He is a "tortured wretch", racked by corrupt policemen, milked by a bribe-seeking bureaucracy and in thrall to the banks. Things went wrong in the late 1990s when the government, in an attempt to soak up unemployment, allowed any type of car to become a taxi and just about any driver to be a cabbie. There are now 80,000 taxis in Cairo, so Khamissi was never likely to see the came cabbie twice.

The conversations build up a portrait of the lower depths of Egyptian society, from whose viewpoint the modern world is just a racket. The saga of the great seat belt scam is a telling example. One cabbie explains that seat belts used to be a highly-taxed luxury, so people would rip them out when importing a car. Then suddenly they became compulsory. The only seat belts to be found cost 200 Egyptian pounds (140 dirhams) - almost a month's salary for some people. And the police started fining the drivers 50 pounds (35 dirhams) a time for not having them fitted, and demanding a bribe from drivers not wearing them. Everyone made money - the police, the government and the seat belt importers - on the back of the cabbie.

All human life is glimpsed through the driver's windscreen and his rear-view mirror. There are some tantalising glimpses of women behind their hijab: the woman who tells her family she is working in a hospital, but changes in the back of the cab into a short skirt to work as a waitress. One driver is smitten with a prostitute - no heart of gold in her case - who teases him because he cannot afford her.

The book is touching, illuminating, and also frustrating: the taxi driver is in the modern world - with its seat belts, mobile phones and bank loans - yet nothing works in the way it is supposed to. Existence is reduced to bread - which significantly in Egyptian Arabic is called aish, or life. What has gone wrong with Egypt is not hard to understand, Khamissi says. "Ultimately what people want is very simple: they want to live in clean housing, they want to eat, and they want to get their children into good schools. Housing, food and education - that is Egyptian politics. Now the cost of food is extravagant and education has declined to an appalling state. It's as simple as that."

Surely, I counter, not everything is bad. If 60,000 people can afford his books, doesn't that mean there is a growing middle class? Khamissi admits that the private sector is making progress and this can be seen in a newly dynamic publishing industry. So there is hope that Egypt will regain its old glory? He pauses and returns to the dispossessed. "Don't forget: the professional class is not more than one per cent of the population."

Alan Philps is associate editor of The National