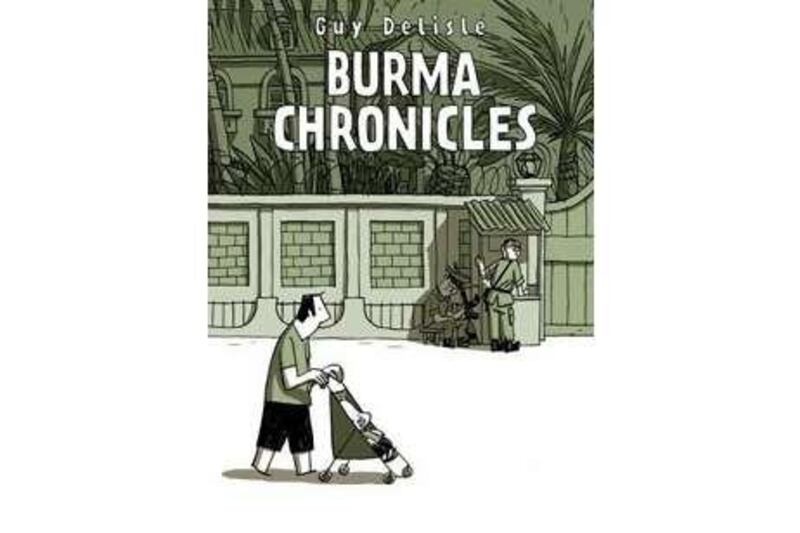

Guy Delisle's third Asian travelogue is another insightful masterwork of the comics form, writes Joe Sacco.

Burma Chronicles

Guy Delisle

Drawn and Quarterly

Dh77

Autobiography is perhaps the easiest refuge for aspiring North American and European comic book artists, which wouldn't be such a drawback if their lives, mostly spent labouring over their masterpieces-to-be on kitchen tables and watching B-movie videos with their bored girlfriends, weren't so frighteningly dull. In fact, being told to "write (or, in this case, draw) what you know" is questionable advice to a cartoonist in his or her early 20s who doesn't know and hasn't experienced much of anything.

Guy Delisle has entered the comics scene like a breath of fresh air, and may all young autobiographically-minded cartoonists fill their lungs with his example. With endless curiosity but without seeming to try too hard, Delisle lives a life worth documenting. He has travelled to Shenzhen, China and Pyongyang, North Korea to supervise animation projects, and he turned those adventures into two critically- acclaimed works of comics (Shenhzen, A Travelogue From China and Pyongyang, A Journey In North Korea).

In both works, Delisle managed to wring the full potential from the comic-book form, which can thrust the reader into a foreign place from the first panel. Repeated imagery - details of architecture, dress and street life - silently follow the reader from page to page in the background, allowing an atmosphere to sink in. Additionally, by varying the size of the drawings a cartoonist can shift a reader's gears, influencing him or her to pass quickly over small, simple panels of dialogue or to dwell thoughtfully on a large, complex cityscape. Since Delisle knows what he is doing, the reader is hardly aware of the manipulations.

In both of his earlier books, the Canadian-born, French-based Delisle proved himself an amusing, self-deprecating, and often insightful guide to places few foreigners get to see or even want to visit. Delisle, who draws himself as a nondescript, beak-nosed figure, was particularly good at letting us know how he coped - or sometimes didn't cope - along the way. In Shenhzen he seemed almost swallowed up by the gargantuan Chinese stage; in Pyongyang he good-humouredly lurched from one totalitarian absurdity to another.

Now he has turned his Asia journeys into a trilogy with Burma Chronicles. Burma, which prefers to call itself Myanmar, is another seldom-visited country, one whose military government has not endeared itself to the international human rights community. This time Delisle travels with his wife, - for our cartoonist guide is now married - who is sent to Burma as a representative of the aid group Medecins Sans Frontieres (MSF), known in English as Doctors Without Borders. (It is not hard to imagine Delisle marrying a woman as adventurous as he is.) They bring their baby son with them.

Because of these new domestic arrangements, Burma Chronicles feels from the start like a different sort of book than Shenhzen and Pyongyang, where Delisle immediately threw himself and his readers into the deep end of strange lands. This time, he is more or less along for his wife's ride, and essentially relegated to the role of house husband. Readers might be forgiven for wishing they were following the wife on her visits to remote missions instead of staying home with the author as he tends to their infant. This is particularly true early on in the book, where Delisle insists on relating what can only be termed "cute-baby" stories. He spends a few precious panels documenting how the baby likes to drop objects in places where they can't easily be retrieved. This might be a jolly family anecdote under ordinary circumstances, but Delisle has taken his readers to Burma, a repressive dictatorship few foreigners will ever visit, and they might begin to wonder when he's going to start showing them around.

It's a slow beginning. At first I was worried that Delisle was going to explore only the few blocks around his house, that part of Burma he could visit while pushing a baby stroller. But he keeps to his own self-assured pace and demonstrates he can integrate his little boy into a greater narrative after all. When he learns that Aung San Suu Kyi, the Nobel Prize-winning opposition leader who would be prime minister if Burmese electoral results were actually respected, lives under house arrest in his neighbourhood, he sets off with his baby to talk his way through a checkpoint and have a look for himself. "I can't imagine they'd keep an innocent dad and his kid from going through," he tells himself. Though he is stopped and sent back by a guard, the incident allows him to provide an insightful, concise (three-panel!) exposition on one of the world's most well known political prisoners.

The episode exemplifies Delisle's diary-like storytelling technique. Rather than well-defined chapters tackling one subject after another in series - say, politics, culture, religion - Delisle uses small encounters or passing conversations to return to these themes as they crop up. It's a loose format, but one that manages to give the reader some sense of Burma as a whole. For example, Delisle touches on the government's control of information several times with great effect. In one chapter he finds some old Time magazines that are missing pages and tells us that a censorship bureau "systematically removes" articles critical of Burma. (The accompanying drawing shows a Burmese official industriously cutting away late at night next to huge piles of magazines and a rubbish bin overflowing with excised pages. Delisle takes much delight in lampooning the state apparatus any chance he gets.) Later, Delisle demonstrates the inanity of what passes for official news in Burma by including a reproduction of a paragraph from the state-run newspaper, which contains "nothing but a list of officials present at a given event." When e-mails sent by MSF to the Paris home office keep bouncing back, Delisle solves the problem by driving to the government's "internet fortress" and telling a technician, "Basically, I think your filter is screwed." With characteristic brevity Delisle informs us that "Burma has two service providers. One belongs to a government minister, the other to his son."

Intermingled with these and other commentaries on the authoritarian state are frequent, bemused depictions of local customs. On one of his strolls with his baby, Delisle, who suffers much in the heat, sees a cabinet in the street containing a pitcher of water and glasses for thirsty passers-by. "I could be dying of thirst," he notes, "you still couldn't pay me to take a sip." He seems more amused, though, by the stains made by people spitting out betel juice in stairwells, the makeshift doorbells hanging down at street level from multi-story buildings and the way Burmese hook their umbrellas over the back of their shirt collars - all of which are wonderfully detailed in Delisle's spare, grey-toned drawings.

In one hilarious episode, Delisle joins in the fun of the water festival, which marks the Buddhist new year. He is always good at pithy, informative explanations: "Traditionally, you wash away your misdeeds by letting others pour water over your back." Whatever the religious function of the tradition, what actually ensues is a citywide water fight where participants employ pails of water, squirt guns and even fire hoses. Delisle's drawings evoke the mayhem beautifully, and he tops off the sequence with a series of wordless panels that show him ducking out of the way and out of range until finally he surrenders to a dignified older woman carrying a bowl of water whom he could probably easily have escaped.

Delisle employs drawings-only sequences elsewhere, namely in three separate chapters where he and his wife set out to holiday in different parts of the region. (Don't worry, the baby is at home safely with a caretaker.) These pages are minor masterpieces of the comics form. Delisle is able to convey sensations like heat and serenity without using a word. His landscapes of the Burmese countryside and his architectural renderings of pagodas and lake houses resting on stilts are always vivid without ever being fussy. On the most striking trip, to Bangkok, Delisle deftly paints a picture of an overwhelming, consumerist mega-city, which contrasts jarringly with the relatively quiet, if repressive, Burma we've come to know. At one point, a ride on the back of a Thai motorcycle taxi is rendered all the more harrowing by Delisle's considerable animator's understanding of depicting speed.

More trips ensue when Delisle - always chomping at the bit to get out of the house - finally attaches himself to a couple of his wife's expeditions and accepts an invitation to visit humanitarian workers in a distant northern region. This is Delisle at his best. The long journeys give him a chance to complain - always humorously - about the long road or the bumpy aeroplane ride; the rural surroundings give him a chance to draw more gorgeous landscapes; and the troubled areas visited give him a chance to expound upon a few of Burma's disturbing realities. In his trip to Myitkiyina, for instance, Delisle tells us about foreign-run (mostly Chinese) jade mines that pay their workers in heroin. He walks down the eerie, silents streets of one village where "at least 86 per cent of the people shoot up at least once a day." Elsewhere, Delisle touches on Burma's many other problems, including Aids and, too briefly, the Karen insurgency and refugee crisis on the Thai border.

Burma Chronicles is strangely short on fleshed-out Burmese characters. Though Delisle details numerous encounters with locals, one never gets the sense he knows any Burmese intimately. In one telling scene, Delisle finds himself with a crippled elderly woman who "talks to me about the past, her youth, Rangoon in its golden days." But Delisle never tells us what she says. She seems critical of the regime and claims, "I can speak my mind," but if she does, Delisle doesn't give us a word of it.

There might be more to this than negligence on Delisle's part. He puts together an informal class for local animators. At one point, a European journalist who Delisle showed around ends up writing an article critical of the Burmese regime. One of the would-be Burmese animators, who works in the government, is now suddenly afraid of losing his car and apartment and spending up to 10 years in jail for associating with Delisle. Our author is distraught: he might be indirectly responsible for getting someone into a mess of trouble. Perhaps it is no wonder that Delisle seldom identifies the Burmese he has met or relates any details the regime might use to identify them. He has tasted firsthand the bitter reality of the country's dictatorship. Despite its hodgepodge of charms and its general good humour, Burma Chronicles leaves the same taste in the reader's mouth.

Joe Sacco is the author of Palestine and Safe Area Gorazde: The War in Eastern Bosnia 1992-1995.