The Faraway Nearby

Rebecca Solnit

Viking

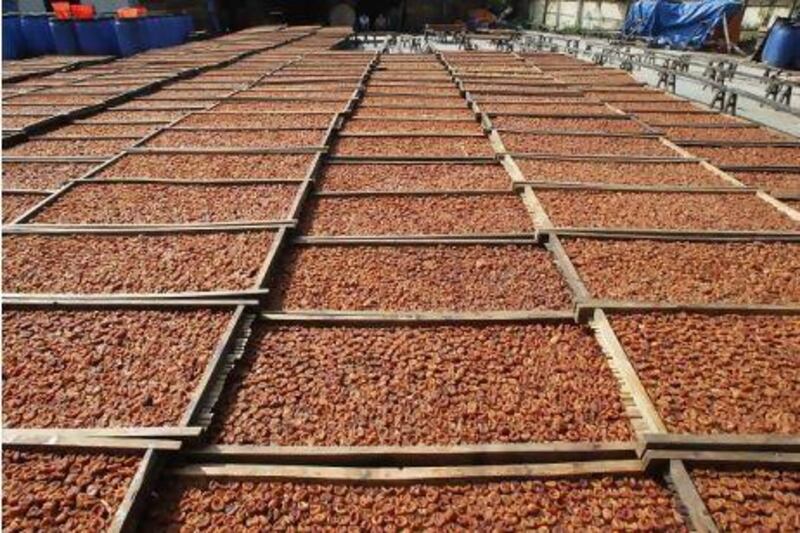

Like a fairy-tale princess, Rebecca Solnit received an ambiguous bequest from her Alzheimer's-stricken mother. Three hefty boxes, approximately 45 kilograms, of apricots from her mother's tree, lugged home after her mother was moved into an assisted-living facility. An overabundance of abundance can be its own kind of punishment, a fairy-tale curse, and the apricots, carefully separated and laid out like a carpet on her bedroom floor to prevent rotting, were Solnit's burden, and her story to tell. "Stories are compasses and architecture," she reminds us at the outset of her magnificent new book The Faraway Nearby. "We navigate by them, we build our sanctuaries and our prisons out of them, and to be without a story is to be lost in the vastness of a world that spreads in all directions like Arctic tundra or sea ice."

Solnit is perhaps best classified as a storyteller, because no other designation would fit her quite so well. She is a writer of superlative non-fiction works of a staggering diversity and range, veering from River of Shadows, her study of the photographer Eadweard Muybridge and the American West, to A Paradise Built in Hell, about the surprising makeshift communities born out of catastrophes such as the 1906 San Francisco earthquake and Hurricane Katrina. The Faraway Nearby can be categorised as an interior travelogue - a travel guide to Solnit's inner depths. It is a memoir of a difficult period in Solnit's life, characterised by her mother's steady decline and her own diagnosis with a pre-cancerous growth and subsequent surgery. But The Faraway Nearby is unwilling to settle for being a parade of tragedies and mishaps. It is, instead, about what comes afterward. "Stories like yours and worse than yours are all around, and your suffering won't mark you out as special, though your response to it might," she tells herself.

Solnit is a reluctant memoirist, and uses her own story as an opportunity to consider the value of stories ranging from Mary Shelley's Frankenstein to that of an Inuit woman named Atagutaluk, driven by desperation to cannibalism. Writing is an opportunity to strip away the layers of politesse that keep us estranged from honesty: "Writing is saying to no one and to everyone the things it is not possible to say to someone." It is a solitary trip into the polar reaches of the self, a journey that, if successful, prompts further solo expeditions. "If you succeed in the voyage," Solnit says, "others enter after, one at a time, also alone, but in communion with your imagination, traversing your route. Books are solitudes in which we meet." The Faraway Nearby is both guide and example, a memoir about the act of remembering.

An astute cultural critic, Solnit was a full-throated supporter of the Occupy Wall Street movement. Occupy hardly appears here, and yet its desire to sing the body politic is everywhere in The Faraway Nearby.

Solnit is asking us to pause, to consider the stories we tell ourselves about our lives, and to rethink the unstated assumptions of our own interior epics. She offers the example of the birdman cult of the Rapa Nui of Easter Island, who risked death to capture the first tern egg of the season, and the concomitant glory that came with it.

Expecting our disapproval, Solnit turns on us, guns blazing: "Only the unfamiliarity of the birdman cult makes us remark on its arbitrariness, since in our society people die in the attempt to climb mountains for no practical reason, kill because of words that insult them or their gods, and revere those who have won a prize handed out by a whimsical jury or because a combination of factors sent a ball into or over a net." LeBron James might dispute her assertions, but Solnit is here to remind us to consider what tern eggs we might be chasing after ourselves. Anger lies buried just under the surface - at her mother, at the capriciousness of her health, at an unjust and unequal society that rewards us for all the wrong reasons. Solnit seeks change, but is wise enough to begin from within.

So how do we change? What levers activate our oft-buried desire to transform our lives for the better? And how do we go about changing ourselves once they do? Solnit is reminded here of Che Guevara, who as a young medical student rode around South America with a friend, in a journey memorialised in The Motorcycle Diaries. Guevara, in one of the most famous moments of his life, spotted a leper colony across a river in Peru.

Espying danger, the forbidden, the prospect of unmitigated suffering, Guevara ventured towards it, and was changed by it: "In what seems to be an epochal act in his life, Guevara jumped in the broad river and swam across it, toward them. The river was a physical space that had become a psychic space, and in crossing the one he crossed the other and arrived at some firmer sense of self and solidarity." The paradox of Che is that in taking the leap, he also eventually undid all of his good works: "He had become a revolutionary out of the most tender-hearted empathy for the suffering he encountered in particular men and women. As a revolutionary he became hardhearted, dedicated to humanity in the abstract and often callous with the individuals met en route."

"We tell ourselves stories in order to live," Joan Didion famously said, but Solnit believes that "stories often tell us, tell us to love or to hate, to see or to be blind." Solnit is the memoirist as philosopher, gently, and then not so gently, urging us to transcend our own frailties, and our limitations. Illness and suffering are stories we tell, but whether they are epics, ending with our triumph, or tragedies, ending with our deaths, we do not yet know.

"Listen," Solnit observes, "you are not yourself, you are crowds of others, you are as leaky a vessel as was ever made, you have spent vast amounts of your life as someone else, as people who died long ago, as people who never lived, as strangers you never met." We are all only loosely fixed stories, like "the apricots fixed in their sweet syrup" that serve as a makeshift solution to her mother's ambiguous bequest.

Solnit's brush with illness coincides with another friend's premature baby, and a third's decline and eventual death. The imminence of death, its sighting over the horizon, is also an opportunity to restart the narrative, to tell a new story: "A major illness or injury is a rupture that invites you to rethink, to restart, to review what matters. It's a reminder that your time is finite and not to be wasted, and in breaking you from the past it offers the possibility of starting fresh." The results can be seen here, in this memoir that refuses to be a memoir. A memoir is a pivot inside, a gaze within that, at its best, reflects the world; Solnit's anti-memoir is a pivot to the outside, a gaze at the world that reflects her own image back at her. A memoir is often an exercise in narcissism; The Faraway Nearby is a book-length primer in the uses of empathy. "Difficulty is always a school," she wittily remarks, "though learning is optional."

We are better people for looking beyond ourselves, for understanding the stories other people tell themselves. "If the boundaries of the self are defined by what we feel," says Solnit, "then those who cannot feel even for themselves shrink within their own boundaries, while those who feel for others are enlarged, and those who feel compassion for all beings must be boundless." Stories give us an artificial sense of our lives' cohesion, but they also help us, at their best, to understand that everyone has their own tale: "We are all the heroes of our own stories, and one of the arts of perspective is to see yourself small on the stage of another's story, to see the vast expanse of the world that is not about you, and to see your power, to make your life, to make others, or break them, to tell stories rather than be told by them."

What do we do with pain? We can let it deform us - make us angry, bitter, enervated. Or we can treat it like Solnit's overabundance of apricots, and make preserves out of them - place them in jars, seal them tightly and keep them for posterity. Our stories, as The Faraway Nearby so richly demonstrates, are not any one thing, but a concatenation of competing, clashing, overlapping narratives. Solnit summarises Atagutaluk's years in words one suspects she might not mind making use of herself someday: "She was stranded, suffered, survived, begat, sustained, was remembered with gratitude and admiration. It was a life."

Saul Austerlitz is a frequent contributor to The Review.