How The Beatles Rocked the Kremlin

Leslie Woodhead

Bloomsbury

Forty-three years after The Beatles' demise, the understandable notion that there's little left to say about them continues to prove false.

Scott Neil and Graham Foster's soon-to-be-published Lennon Bermuda is a short, detailed account of John Winston's stay on the island in the summer of 1980, and now comes another geographically specific title, Leslie Woodhead's How The Beatles Rocked the Kremlin.

Substantive and diligently researched, Woodhead's book argues that The Fab Four's music was a powerful, uniquely seditious force in the Soviet Union. Indeed, Artemy Troitsky, celebrity rock guru and the author's "essential guide to the Soviet Beatles generation", holds that the Fabs were more decisive than nuclear missiles in winning the Cold War for the West.

It's a bold claim, and one which draws the reader into a book that will probably appeal to political historians as much as it does fans of Help! For while Woodhead's book is certainly Beatles-centric, it also takes a long, perspicacious look at more than six decades of Soviet cultural censorship. Mapping everything from Maxim Gorky's 1928 condemnation of US jazz ("It is like the amorous croaking of a monstrous frog") to the imprisonment of two members of feminist punk band Pussy Riot in October 2012, it is partly a miscellany of Soviet paranoia from Stalin to Putin. One also comes to understand why grown men and women wept openly when Paul McCartney finally made it to Red Square in 2003. Woodhead has excellent credentials for the job in hand. He was taught Russian at the Joint Services School For Linguists in Fife, Scotland, from 1956, and as he recalls in his 2006 book My Life As A Spy, his National Service took him to West Berlin, where he monitored the communications of Soviet pilots flying in and out of East Germany.

Best known as an award-winning documentary filmmaker, Woodhead has also worked extensively in the Soviet Union since the 1980s. But a much earlier entry on his CV made Soviets particularly willing to share their love of The Beatles with him.

In August 1962, Woodhead made the first-ever film of the band while he was working for Granada Television. He shot The Beatles playing live at The Cavern in Liverpool just four days after Ringo Starr replaced Pete Best on drums. When Woodhead recalls chatting with Paul McCartney, then 20, in the pub afterwards, we witness the author's acute descriptive skills: "My drinking companion was a jaunty young man with the eyes of a spaniel implacably confident of its charm," he writes.

Though the USSR's state record label Melodiya (one only has to imagine an imprint run by, say, David Cameron to grasp the hideousness of the concept) eventually made small quantities of A Hard Day's Night available in 1986, accessing Beatles music, rather than state-sanctioned songs about steel output, had previously involved covert ingenuity and great personal risk.

Record-scratching machines at Soviet airports rendered many Fabs discs imported by the few at liberty to travel useless, but "records on bones" - foldable recordings of western radio broadcasts made on medical X-ray films - were easier to distribute and much harder to police.

That even these low-fidelity artefacts were so prized speaks volumes, and naturally Woodhead works hard to decipher the precise appeal of The Beatles' music for Soviets contending with extreme cultural repression.

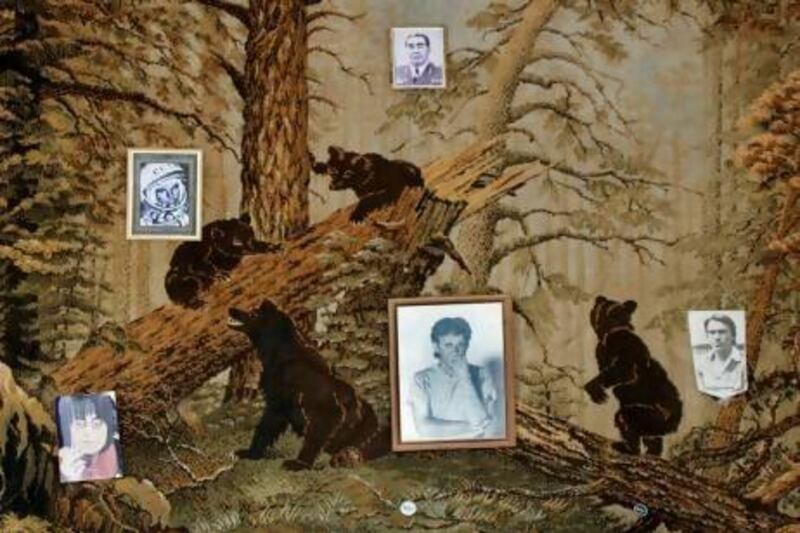

Numerous interviewees, such as the veteran Russian rock stars Andrey Makarevich and Boris Grebenshikov and the Fab's superfan Kolya Vasin tell him that, for them, The Beatles' music exuded a very tangible sense of freedom and exuberance. In a society that sought to eliminate God, it also seems that The Beatles' music had a quasi-religious dimension for many Soviets. The home of the aforementioned Vasin, a man so devout he named his cat Hey Jude, is a shrine dedicated to John Lennon overlooked by Beatles angels. Elsewhere, Soviet filmmaker Maxim Kapitanovsky reports, "We had a gap in our souls. The Beatles filled that gap." Over time, Woodhead shows that the cultural commissars' fear of The Beatles was a fear of the unknown; of something potent, amorphous and pervasive. In a state in which Sergei Mikhalkov, writer of the Soviet national anthem, denounced rock music as "the moral equivalent of Aids", The Beatles were soon subject to the distorting lens of propaganda.

One of the silliest examples - a contemptuous Pravda article that claimed The Beatles sat on the toilet while performing - only served to underline the ridiculousness of what the state was peddling. "The Beatles were the first to show us that there was something wrong with what we'd been taught by our Soviet rulers," another rock star, Sasha Lipnitsky, informs Woodhead further in. "We were told that people in the West were the enemy, not our neighbours on the planet."

Kolya Vasin offers the lovely metaphor of The Beatles being the holes in The Iron Curtain through which he and others like him breathed, but it's another of Woodhead's interviewees, the Soviet-American journalist Vladimir Pozner, who flags up some of the most glaring and blackly humorous fissures in Soviet propaganda.

"People would watch some report about the evils of capitalism with pictures of poor blacks and drunks on skid row," Pozner says. "But they would turn down the commentary, and focus instead on the miraculous displays of clothes and furniture and food in the shop windows."

Though Woodhead's incisive, fact-rich writing is leavened with humour, there is, of course, a very dark side to his story. Leaned upon by KGB heavies, Stas Namin of the group Tsvety (Flowers) had to quit music to become a photographer after the press called his band "the Soviet Beatles". Artemy Troitsky was expelled from school as a teenager for playing Beatles records to his fellow pupils, and we learn that even jokes spun from the punning possibilities of "Lennon" and "Lenin" could meet with harsh punishment.

Tracing leadership shifts from Krushchev to Brezhnev to Chernenko to Gorbachev, the author shows that Soviet cultural censorship was not subject to a gradual linear thaw - rather it was a case of one step forward and two steps back. The mercifully brief Chernenko era was particularly regressive, the said premier withdrawing a film about Abba from cinemas and accusing the West of trying to "poison the minds of Soviet people".

Woodhead's book is a fascinating and scholarly read, then. His very personal Beatles connection - clips from his vanguard film were legion when John Lennon, then George Harrison died - seems to have fuelled a labour of love that will likely remain the definitive account of The Beatles' impact on the Soviet Union.

Completists should know that the book includes a number of previously unseen Beatles photographs shot by the author in 1964, and that it explores its subject from all angles. I particularly liked rock star Vladimir Matietsky's account of how viewing The Beatles covertly at a distance led to some curious inversions.

"Some fans believed that The Beatles loved Soviet pop music," says Matietsky. "The legend insisted that the band would gather in Lennon's attic to try and listen to Russian radio. Some kids built a complete alternative world with this stuff. They told stories of how British kids who tried to dance like Russians would be deported to the Falkland Islands."

James McNair writes for Mojo magazine and The Independent.