Taipei is the latest example of what novelist David Foster Wallace called US citizens' "straight-line pursuing this flat and short-sighted idea of personal happiness". Tao Lin's protagonists, through their extended socialising and pathological consumption of narcotics, seem desperate to be happy, but consistently fail.

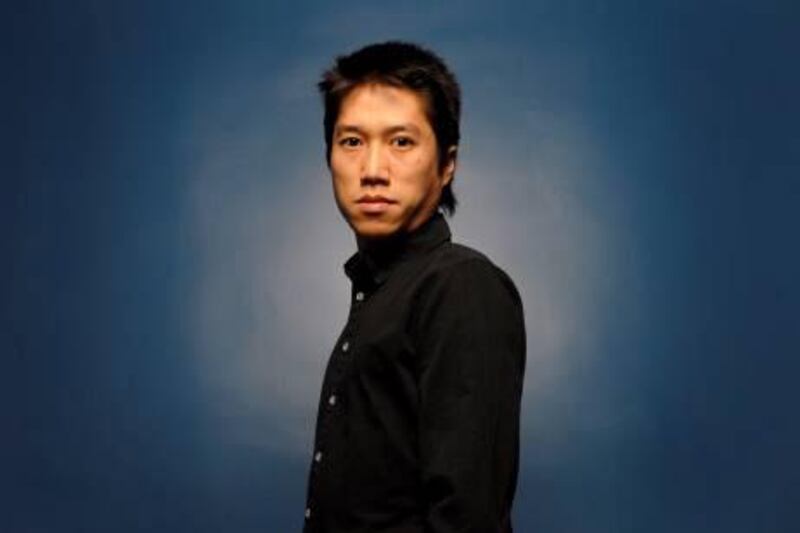

It is a sad, sometimes infuriating novel, heavily indebted to its predecessors - Wallace's work among them - and has already been judged as much for its contents as for the notoriety of its 29-year-old author.

This is Lin's third novel. The first, Eeeee Eee Eeee, was a Kafka-infused account of the life of a pizza deliveryman. The second, Richard Yates, began with two characters, Dakota Fanning and Haley Joel Osment, meeting on Gmail chat, presumably using pseudonyms though this is never made clear, and was marked by its Beckettian peculiarity and deliberately monotonous voice.

Charles Bock, writing in TheNew York Times, said, by the end - I paraphrase - Taipei made him feel like committing suicide. For the US publication of Taipei, an interview with New York magazine saw Lin show off his collection of Xanax, heroin, cocaine, Percocet, trazodone and tramadol, and accuse the interviewer of stealing his Adderall, a drug more commonly used to treat people suffering from attention deficit hyperactivity disorder.

Lin's media image aside, while this latest work is visionary in places, it suffers from unoriginality in many others. Paradoxically, Lin is saved by Taipei's dissimilarity to any of his previous novels, functioning best as a waypoint on a meandering trajectory, allowing him the continuing choice between relative commercial success and artistic fulfilment.

It's an enviable position, as was his relationship with his former US publisher Melville House - one of the launch pads for his ascent - that, Lin claimed, would publish whatever he wrote, even if they didn't like it.

The book's central character, Paul, is a writer living in Brooklyn. The vagaries of his life provide what there is in the way of a narrative arc. He goes to parties, takes drugs, falls in and out of friendships and relationships. As the novel continues, his relationship with an on-off girlfriend, Erin, develops, and so does his drug use. They get married; he becomes progressively more miserable. His affinity to his parents in Taiwan is described during a holiday there with Erin, though it is never fully explored and is often swamped by Lin's all-encompassing prose style and the grandness of his project. This seems to be an unrelentingly honest account of what it's like to be Tao Lin at this particular stage in his career. Lin claims many of the events in the novel are based on his personal experiences, and there is no reason to doubt him. Characters go to superhero action movies and live-tweet the results while high on heroin; they get pulled over by the police and laugh about it; they film themselves on their MacBooks making deliberately regressive parodies of films in which they'd like to star.

Prose-wise, the echoes of Douglas Coupland, Chuck Palahniuk and Wallace, who shares Lin's hyper-attentive relaying of detail, are deafening. The similarities to Bret Easton Ellis, who provided a cover blurb for the book, are even more profound, and though well-rehearsed, are worth listing again: the citation of brand names, whether pharmaceutical, sartorial or technological; the long cast of incidental acquaintances; the name-dropping of celebrities; occasions of memory loss; the denudation of identity, whether in Ellis through wealth, privilege and social status, or in Lin, through technology, sociological displacement and fame. Both share a sense that what society promotes as being beneficial often drowns out our individuality. They both use similar imagery to suggest how identities may be compromised, for example, a character catching sight of himself in the mirror and failing to recognise himself, or characters having an atypical facial expression relayed back to them by a third person.

Lin is much more cruel than Ellis to his readers. If we look at Less Than Zero, Ellis's debut and a work frequently compared to Lin's, we see a book that is all the better for a narrator never completely being part of the world he describes. Such works present the public with the gift of voyeurism without the paycheque of slavishly following the thoughts of superficial characters. Paul's thoughts are often dull, solipsistic, paranoid and vague, as drug addicts' ideas often are. It's realistic - as Lin would say, he identifies with his characters, and Ellis doesn't - but as literature, would be more valuable if Ellis hadn't already done it more genially 30 years previously. Lin may be living his stories, and as such, is undoubtedly an important artist, but this doesn't automatically make him an interesting one.

Where the book comes into its own, and where it may more honestly be described as "of its time", is a sense that the lead character's psychological experiences are being fused with a cloud-like, virtual, digital consciousness outside the human body. There is something futurological about this, something akin to William Gibson's predictions regarding the internet, something mystical and/or related to Buddhist concepts of rebirth. Lin's approach, if not the idea itself, feels genuinely new.

"Was this how people sustained relationships and sanity?" reads one passage. "By uninhibitedly expressing resentment to unconsciously contrast an amount of future indifference into affection?" Such ideas are as unexplained as they sound here, but hint at bigger metaphysical questions. Later: "He couldn't ignore a feeling that he wasn't alone - that, in the brain of the universe, where everything that happened was concurrently recorded as public and indestructible data, he was already partially with everyone else that had died. The information of his existence, the etching of which into space-time was his experience of life, was being studied by millions of entities, millions of years from now ..." Is Lin referring to a future, universe-wide consciousness, separate from individual identity, outside the human body? Elsewhere, his use of Gifs, Facebook and Twitter in similes and dialogue are less successful and will date quicker.

The author has an obvious gift for imagery: "After blearily looking at the internet a little … he lay in the darkness … finally allowing the simple insistence of the opioid, like an unending chord progression with a consistently unexpected and pleasing manner of postponing resolution …" This quotation is barely half of a paragraph-long sentence, and is fairly typical. Sometimes, these extended passages become too clunky and confused, as the writer purposefully extends sentences beyond their limits. He has a tendency to introduce clauses at the end of sections that do not obviously relate to what they follow. Lin has revealed in interviews that he employed a set of rules while writing: when to use commas or verbs, or stock phrases to avoid. While such habits are presumably rewarding for him, such a lack of kindness to his readers has its consequences. It makes his prose easily identifiable, but it often veers into the self-indulgent, whimsical, and simply vague.

For someone so keen on irony, it is unavoidably ironic that an author so often held up as being plugged into the zeitgeist uses so many old ideas. Lin's pronouncement in a 2011 essay that he is currently "most interested in reading/writing novels that aren't improvements on or innovations of other novels" might be satisfying for him. For everyone else, his strengths, and appeal, lie in the untrammelled paths he makes where others are too fearful to tread.

Rob Sharp is a freelance journalist based in London..

Follow us

[ @LifeNationalUAE ]

Follow us on Facebook for discussions, entertainment, reviews, wellness and news.