In April 1849, Fyodor Dostoyevsky was arrested in St Petersburg for his role in a political plot against Tsar Nicholas I and sentenced to death. He and his co-conspirators were led before a firing squad but, in the end, given a mock execution. However, his last-minute reprieve did not result in release. His sentence was commuted to four years of exile and hard labour in a remote Siberian prison camp. He suffered severe hardship there but lived to tell the tale. "Here was our own world unlike anything else," he wrote in a fictionalised account of his incarceration; "here was the house of the living dead."

A hundred years later, paranoia and punishment continued to be dominant forces in Stalin's Russia. Names and ideologies changed but the brutal mechanics remained the same – that is until they were cranked up. Replacing the Tsar's autocratic command was the Man of Steel's iron grip. The imperial secret police, the Third Section and later the Okhrana, mutated into Soviet state security outfits that included the Cheka, formed after the 1917 October Revolution, and the infamous NKVD, which kept the country safe by purging its population. The Katorga camps of the Russian Empire gave way to the Soviet Gulag.

A powerful new book about how one ordinary, innocent man – one of millions – fell foul of Stalin and paid the ultimate price highlights the extreme measures taken to protect the Russian state and prolong its dictator's misrule. Throughout Stalin's Meteorologist: One Man's Untold Story of Love, Life and Death, we see history repeating itself and tyranny with a twist. In 1934, the highly respected head of the Soviet Union's meteorology department, Alexey Feodosievich Wangenheim, was arrested and deported to a gulag in the frozen north. Unlike Dostoyevsky imprisoned in "the house of the dead", Wangenheim was incarcerated in what French author and Russophile Olivier Rolin terms "the island of the dead". When Dostoyevsky's four-year sentence was up he was freed; after serving his 10-year sentence, Wangenheim was executed.

Rolin's book examines the violent upheavals that convulsed Russia in the first half of the 20th century. Towards the end, Rolin also touches on his travels across the country, within the Iron Curtain and beyond, and the attendant history which fascinates him – "even if, paradoxically, it is that exerted by some places of horror".

But the focal point of the book is Wangenheim, specifically his short life, his deep love for his family and his iniquitous death.

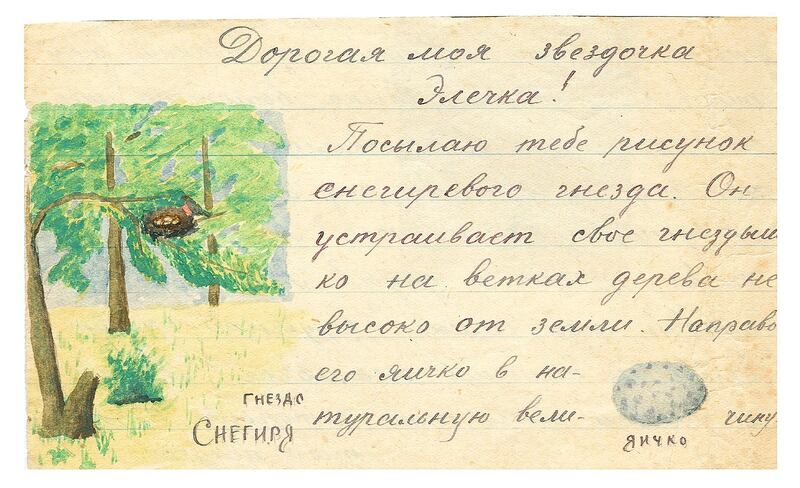

Rolin begins by outlining the circumstances that led him to cross paths with Wangenheim. After speaking at the University of Archangelsk in 2010, Rolin flew onwards to the Solovetsky Islands, an archipelago in the White Sea far removed from the tourist trail. There he came across a 15th century monastery and learnt that from 1923 it housed the first gulag forced labour camp. His curiosity piqued, Rolin made a second trip in 2012, where he discovered an album of letters and drawings of the natural world which one of the inmates – Wangenheim – sent home to his wife, Varvara, and his young daughter, Eleonora.

Wangenheim called Eleonora his "little star" and his wife and daughter were "the only glimmer in the darkness". Charmed by his images, moved by his words and horrified by his fate, Rolin set out to uncover Wangenheim's story, up to when that star slid from view and his darkness became absolute.

Wangenheim was born in 1881 in a Ukrainian village. His father was a minor nobleman and amateur meteorologist, and it was through him that young Alexey became interested in the land and the sky, the clouds and the elements.

He studied in Kiev and Moscow, did his military service and emerged unscathed from world war, the revolution and civil war.

"Let us move on quickly," Rolin interjects. "We're not writing his CV." At which point he ups his pace, briskly covering Wangenheim's marriage, his party loyalty and each stage in his illustrious career. The pinnacle was becoming the first director of the USSR's Hydrometeorological Centre in 1929. This was a big responsibility for a land so vast but Wangenheim applied himself with zeal. Referring to the service as "my dear/beloved Soviet child", he built an extensive system that took temperatures and produced forecasts – not for the benefit of holidaymakers but the construction of socialist agriculture.

But after a steady rise to national hero-status there came a sharp fall from grace. When a close colleague was arrested and questioned, he claimed that within the centre lurked a secret counter-revolutionary movement fronted by Wangenheim, a man "of an authoritarian and careerist temperament, politically hostile to the party". Wangenheim was charged with being a saboteur and spy. He proclaimed his innocence but to no avail.

"He did what he could, but he could do nothing," Rolin writes. "The game was lost in any case. The fact was, there was no game, the outcome was a foregone conclusion."

That outcome was 10 years' "rehabilitation" through labour at the Solovki Special Purpose Camp. "I am utterly alone here," Wangenheim wrote in 1935, a year into his sentence. "I'm a misfit, a white crow." For this part of his book, Rolin's narrative takes the form of stitched-together excerpts from Wangenheim's letters. This brings us closer to the book's protagonist.

Wangenheim writes often to Stalin and his henchmen, gets no response to his appeals and yet remains faithful to the party. He recounts to Varvara his day-to-day routines and his feelings. His beautiful drawings to Eleonora (a sample of which are included here) are not merely splashes of colour: they constitute lessons in arithmetic and geometry and a "long-distance conversation between a father and his very young daughter, whom he would never see again".

This section of the book is a chronicle of suffering and endurance. However, as this white crow shared a prison with zeks (convicts) who were like-minded intellectuals, he wasn't completely lonely. Also, being afflicted with a nervous disease, he was spared back-breaking toil and instead worked in the prison library where he taught, studied and read. Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn's Ivan Denisovich starved, slaved and "sweated blood" in his frozen-over hell; Alexey Feodosievich had an easier ordeal.

Not, though, at the end. When hope began to fade, despair set in. "I have become this utterly useless person who gives lectures to prisoners, and will be consigned to oblivion on this island." But the authorities had other plans. Wangenheim's case was reviewed and he was sentenced to an additional 10 years, denied the right to send or receive letters, and transferred in a convoy to the mainland and an undisclosed "faraway camp", or unmarked grave. Varvara never heard from her husband again.

Through dogged sleuth-work and rigorous research, Rolin has helped fill in the gaping blanks in Wangenheim's life. For the few niggling grey areas that remain, he resorts to educated guesswork and presents a plausible version of events. Two particularly off-limit episodes are brilliantly and chillingly recreated: Wangenheim's interrogation and intimidation in a "penalty isolator" cell in the dreaded Lubyanka, the headquarters of the secret police and "home of the reverse alchemy that transformed gold into worthless lead"; and his last, terrifying journey to a forest where he was cold-heartedly and bureaucratically turned into a statistic, yet another victim of Stalin's "repressions", or massacres.

This is a bleak book about an unspeakable tragedy. But Rolin's tale – translated with aplomb by Ros Schwartz – is so captivating that, once begun, it is impossible to back off or look away. The grimmer it gets, the more we appreciate the pockets of beauty and rare moments of calm: Wangenheim's clever riddles for his daughter; his meditations on clouds; his delight in pottering in the prison garden, sampling frozen rowanberries sprinkled with sugar, and receiving a pair of boots ("I leapt around in the snow like a hare"); his optimistic belief that he will be released in 1944 at the age of 62 .

Rolin stresses that Stalin's Meteorologist is no scholarly work. Yet while it functions perfectly well without an index or footnotes, it could have benefited from maps and a glossary. Otherwise, it is hard to fault it. By turn gripping and poignant, Rolin's book takes us into "the sinisterly preposterous world of Stalinism" and provides a valuable portrait of "this man dedicated to the peaceful observation of nature who was crushed by the fury of history".