Jim Crace’s 12th novel isn’t a detective story, as such, but it certainly brings out the Hercule Poirot in you. The identity of the book’s omniscient narrator is only revealed towards the end – and even then we don’t get a name.

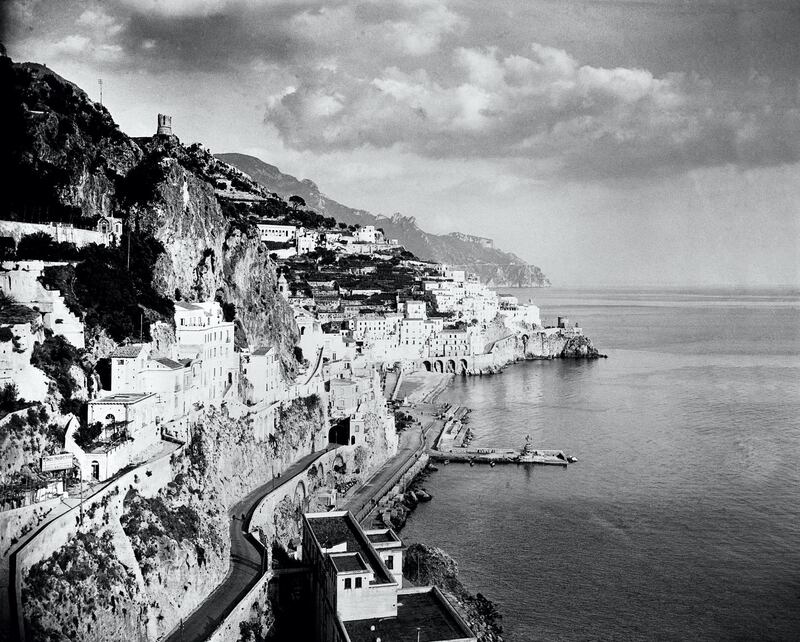

Crace also enjoys a cat and mouse game with his readership regarding where and when The Melody is set. When I typed in the clues I thought might help, Google was largely unforthcoming, so my best guess would be a seaside town in Italy somewhere between 1912 and 1950.

Tantalisingly, knowingly, the author has left a trail of breadcrumbs which appears to lead nowhere. This is strangely pleasing though; a deftly-executed ruse.

The book's plot centres around the trials of Alfred Busi, "Mister Al", a well-known local singer and songwriter who is mourning the recent loss of his much-loved wife, Alicia.

Described as "a calm, distinguished man" in his sixties, Busi is childless and lives alone in a crumbling but picturesque villa by the sea. He has carried a gryphaea or Devil's Toenail fossil in his pocket as a talisman since he found it age 12, but now grief has crushed him.

“His wife had carried off his songs,” Busi comes to realise. “His appetite for performing had been cremated with her bones.”

From his wrought-iron balcony at the end of the town’s promenade, Busi can see “the bosk”, a “tangled, aromatic, salt-resistant maze of sea-thorn, carob and pine scrub.” Some in the town believe this forested headland still harbours a pocket of feral human beings, and these “primeval anthropoids” are also rumoured to descend into the town at night in search of food.

Busi’s already deep sense of unease increases late one night when, investigating the tinkling of Persian bells that signals the opening of his larder door, he is attacked and savaged by what he believes to be a feral child.

We readers are never quite sure if these wild inhabitants of the bosk are the stuff of myth, allegory or fact, but they enable Crace to develop one of The Melody's key themes, namely fear of the outsider, of otherness. But Busi, unlike many in his town, does not condemn the bosk-dwellers. Indeed, he fully understands their predicament and needs.

The book only has a few other key characters but each of them are beautifully drawn. Terina, for example, is the impeccably dressed sister of Busi’s late wife, Alicia. Terina and Busi are close, but their familial relationship is complicated by the fact that she and Busi once had a fling prior to he and Alicia becoming an item. Terina’s son Joseph, meanwhile – at one point described by Busi as “a moneyed loud mouth and a fool” – is also a pivotal character.

Although he claims to have his uncle’s best interests at heart, he actually has designs upon Busi’s villa. Joseph and his fellow investors need to oust Busi, albeit temporarily, so that they can redevelop his property and the adjoining villa as The Grove, a proposed plush housing complex to be sold for exorbitant prices.

The way in which the (sometimes) heavy hand of gentrification can erase memories, traditions and even lives, is another of The Melody's key themes. And when the seamy journalist known only as Sobriquet interviews Joseph about the town's marginalised poor, Joseph's expressed prejudices are shocking even before Sobriquet re-tools them for maximum sensationalism ("He was not a writer who kept his distance from the trite or the theatrical," writes Crace, himself a former journalist, distilling Sobriquet's essence into a single line).

Throughout the book, Crace’s measured, subtly captivating prose is often exquisite. Waves on the sea are as “stiff and eggy as meringues”. Fearful vagrants foraging for food “lift the lids and turn the bins as carefully as maids unpacking porcelain”, and Sobriquet’s cat “raises the eyebrow of his back at every passer-by”.

Various heartbreaking misunderstandings between Busi and Terina are also masterfully sketched as the pair blunder along, each of them all the other has, really, but obliged to maintain a certain amount of distance and propriety for the sake of the late Alicia’s memory.

The book’s singular atmosphere is maintained right until the end, when Busi, Terina, Busi’s young next door neighbour Lex and the story’s mysterious narrator head off on a picnic for Busi’s 70th birthday. It is finally time to scatter Alicia’s ashes, which have hitherto sat in an urn atop Busi’s piano, and naturally the day ahead is full of memories and portents for the widower.

Although you couldn't describe The Melody as a page-turner per se, it certainly has its own curious momentum. A fine book about ageing and grief and the way in which the folkloric can impact upon real life, it's another choice example of this twice-Booker-nominated English writer's unique gift.