You Are One of Them

Elliott Holt

Penguin Press

You Are One of Them, Elliott Holt's captivating debut novel, brings to mind EM Forster's famous quote about loyalty: "If I had to choose between betraying my country and betraying my friend I hope I should have the guts to betray my country." It is a study of friendship and its parameters, with particular emphasis on the energising or enervating effects of trust and betrayal. Forster's line suggests a one-or-the-other binary, but Holt's characters leave friends and countries high and dry in exchange for loftier goals and worthier political causes. Moral dilemmas alternate with sly perfidies. We read, we're gripped, and find ourselves contemplating a stream of searching questions: When is lying justified? To what, if anything, should we pledge allegiance? And can we forgive best friends everything?

Holt's protagonist, Sarah Zuckerman, is a shy, gauche 10-year-old in 1980s Washington, DC. She would be lonely, too, were it not for her popular and charismatic best friend, Jennifer Jones. The Cold War is at its iciest, the nuclear brinkmanship between the United States and Soviet Union most keenly felt by Sarah's mother, a stress-case riven by anxiety disorders and panic attacks. Terrified by her mother's premonitions of impending doom, Sarah decides to write to Yuri Andropov and plead for détente. Jenny copies her, penning a letter too, and both girls are amazed when she gets a reply. Sarah's letter goes unanswered. Jenny's is published in Pravda and the western news media goes wild. Jenny accepts the Kremlin's invitation to visit the USSR and is swiftly transformed into an international media starlet - a peace ambassador and a Soviet propaganda tool. Fame eventually spoils Jenny, Sarah is sidelined and the friendship is fraught, then founders. Just as Sarah starts to contemplate life without her friend, Jenny and her parents are killed in a plane crash.

So runs the first section of the novel, the bulk of it told in flashback, with Sarah's happy nostalgic memories becoming tainted then overshadowed by failure and loss. The second and last part takes place in Moscow 10 years later. We switch gears and change direction from a tale of youthful travails to one powered by and paced with mystery and intrigue. Sarah has received a letter out of the blue from a Russian girl called Svetlana who met Jenny all those years ago on her visit, and who now claims her death was a hoax. Sarah trades Washington, "a swampy city of wonks", for the Soviet capital, "a furtive city", its inhabitants "as closed and guarded as fists", in search of the truth. Despite feeling small and alienated, she identifies with the Russians' "predilection for the tragic"; "Surely this was a place where I wouldn't have to apologise for not being happy all the time?" We accompany her as she ingratiates herself with Svetlana and other natives, and mingles with a hotchpotch expat crowd. But her most significant contact is with the enigmatic Zoya. Could she be Jenny? And if so, what is she doing in Moscow? Most important of all, why did she fake her death?

There is much to enjoy in this deft, cleverly orchestrated novel. It is one of those books shorn of dramatic irony and knowing winks; instead Holt has us as baffled, as frustrated, as wrong-footed and as eager for answers as her protagonist. The plot, though ingenious, isn't wildly original (the faked death is a standard trope of many substandard thrillers) but the exotic setting and fish-out-of-water confusion both increases the tension and enables Holt to successfully digress and showcase a foreign city in all its splendour and cruelness. To a large extent, then, You Are One of Them has a distant forebear in The Third Man, with Jenny Jones as the back-from-the-dead Harry Lime, Moscow replacing Vienna, and Holt as wily and adept as Graham Greene at concealing vital truth in a fug of mystery.

If Holt's opening Washington section set the scene and sketched the characters, then her Moscow segment is the crux of the book, the main act, containing as it does the main drama on the main stage. Her players don't fluff their lines and the backdrop doesn't wobble thanks, perhaps, to Holt herself having lived and worked in Moscow for two years in the mid-1990s. The wealth of insider-info helps it stand out from the glut of run-of-the-mill expat novels: along with Moscow topography that actually feels traversed rather than culled from a Lonely Planet guide, we get Russian slang, sayings, superstitions, traditions, quirks and even frequent chunks of language. For the sheer absurdities, not to mention heartache, inherent in modern-day Russian life we would perhaps have to turn to a native like Ludmila Petrushevskaya and her morbid little fairy-tales. But for an outsider, Holt is as competent at recreating post-perestroika 1990s Moscow as AD Miller was at portraying its 21st-century equivalent in his Booker Prize-shortlisted Snowdrops.

That's not to say Holt's novel is without its flaws. While she may be good at painting in local colour she unfortunately doesn't know when to stop. As Sarah acquaints herself with Moscow, Holt exhausts us with extreme sightseeing, whisking us down every significant street and around every museum and gallery. Unlike the judicially sprinkled and always informative cultural differences and habits, this kind of observation is thick, unnecessary padding. Holt is also prone to needless explication, as if lacking faith in her readers' knowledge. Yuri Gagarin, we are told, was the first man in space. Pushkin, we hear, was a poet. (If this was narrated by a younger, more naive Sarah in Washington, it would be effective, but as it is a decade on, it is not a child testing out her accrued wisdom but a young woman patronising.) Worse are the servings of mangled foreign language for supposed comic effect: men in cahoots with each other are "thick as burglars"; "up your bottom" goes one drinking toast. And is it obligatory for every novel set in post-Soviet Russia to refer to the place as the "wild East"?

But Holt is a talented writer and quickly rectifies one lopsided sentence with a succession of faultless pages. Her novel is all the more interesting for taking place in a Russia trying to "grow out of its awkward teenage capitalism", unlike the glut of novels set before and after 1996 and peopled with menacing KGB officers and flashy oligarchs. As a result, Holt's characters feel less like carbon-copy stick figures and more like credible human beings adapting to change. Sarah, the main non-Russian, is the most believable of all. She comes alive when poignantly describing the many "defections" in her life (her sister who died, her father who absconded, and then Jenny) and when she considers herself "defective" for being regularly betrayed and misused by people. She is arguably at her most real when on her sleuthing mission and navigating the smoke and mirrors that stymie her attempts to verify the facts surrounding her friend's death.

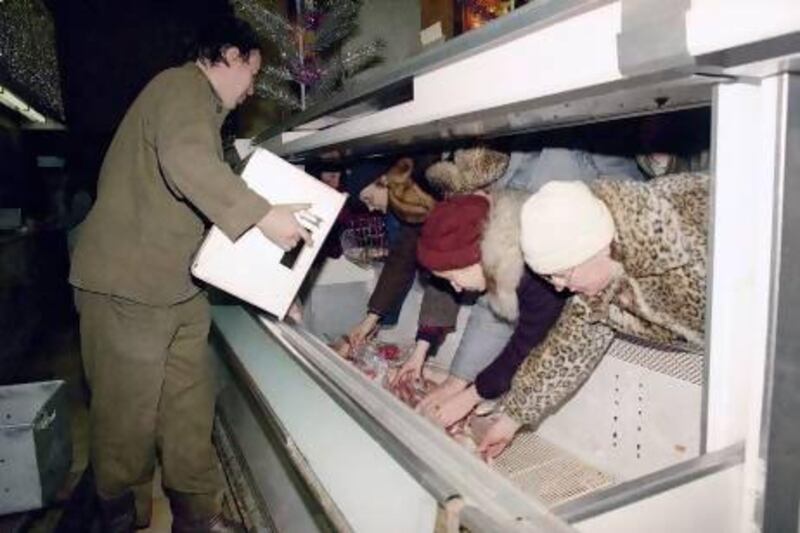

You Are One of Them is a novel of opposites, from the face-off between two rival superpowers, to its two leads - one plain, one a golden girl - to its preoccupation with truth and lies, and yes, trust and betrayal. Holt's ending leaves the reader in limbo, and will disappoint those that like their novels topped and tailed. However, the ambiguity works. Life doesn't always throw up neat answers, especially in a land that disorients those unaccustomed to it. Holt's Moscow is a city full of broken lifts, bad teeth, sallow complexions, alcoholic expats, desperate prostitutes, mafia kickbacks, knock-off goods and busybody babushkas - but it is also a city full of hope. Her characters don't always get those answers they require but hoping is half the battle.

At one point early on Sarah tells us that Jenny had trouble with grammar at school - "the subjunctive confused her". Much later, when learning Russian in Moscow, Sarah practises the subjunctive mood: "I would have gone to the film if I had had a ticket." It can't be a coincidence that Holt's two characters wrestle with the same grammatical form, one that is used for states of unreality. This incredibly tense and quietly powerful first novel highlights the unreality of staying afloat in a foreign land together with the unreality of reclaiming that which we had long ago given up for lost.

Malcolm Forbes is a freelance essayist and reviewer