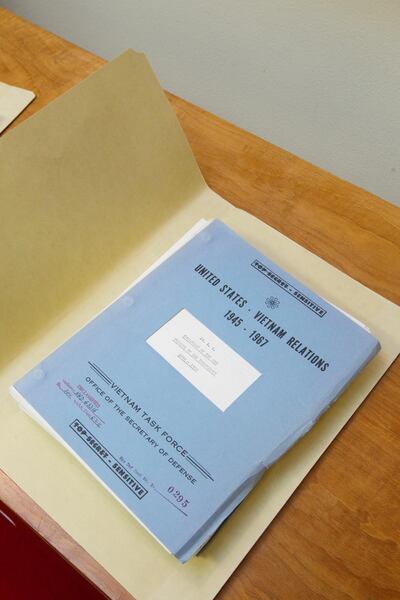

Daniel Ellsberg, the most famous government whistleblower of the pre-Snowden era, in 1971 leaked to American newspapers the so-called "Pentagon Papers", a tranche of highly-classified Pentagon documents detailing not only the government's shockingly haphazard handling of the then-raging Vietnam War but also its very intentional and systematic job of covering it up.

Ellsberg was working for Rand Corporation when he copied the trove of documents with which he would later become synonymous. As he writes in his new book, The Doomsday Machine: Confessions of a Nuclear War Planner, during the media frenzy that accompanied his life from his surrender to the United States Attorney's Office in Boston in 1971 to his espionage trial in 1973, there was one question from reporters that he tried to answer as vaguely as possible: how long did the document-copying take?

Ellsberg tried to avoid the question because a truthful answer would have raised a far more pressing question immediately. Since the copying time was much, much longer than would have been necessary for the Pentagon Papers alone, the natural follow-up question would have been: what else did you copy?

This new book answers that question. Prior to his stint at the State Department, Ellsberg had worked as a consultant for Rand at “the highest levels of the US national security system,” concentrating on the government’s most sensitive documents concerning averting, deterring, prosecuting and surviving a nuclear war with the Soviet Union.

Ellsberg copied enormous amounts of these documents as well. He entrusted these "other Pentagon Papers" to his brother, who hid them in a bluff overlooking a municipal dump in New York's Westchester County. Then, in one of the baroque bits of stagecraft that fill The Doomsday Machine, nature intervened: Tropical Storm Doria struck New York in 1971, burying all those classified copies under a landslide of rock and earth – all of which was then used as landfill for a nearby condominium and promptly covered in cement. The papers were lost.

But in the 45 years since, a combination of dogged investigation and the advent of the Freedom of Information Act have cobbled together enough of those “other” Pentagon Papers that Ellsberg felt sufficiently corroborated to write a book on the subject.

The pun is inevitable, but even so: this is incalculably more explosive material than anything in the Pentagon Papers. The original documents Ellsberg brought to light revealed a corrupt government lying to its people about its fumbling of a proxy war being fought in a far-off land – bad stuff, certainly, bad enough to start the avalanche that would eventually bring down a US president. But these new revelations – not necessarily originated by Ellsberg but with the imprimatur of a man who had seen it all first and very nearly told the world about it half-a-century ago – involve a threat to every living thing on Earth.

The book ranges fairly widely – the Allied bombing campaign against German cities during the Second World War comes up, and there’s naturally a very detailed chapter on the Cuban Missile Crisis, in which US president John F Kennedy promised “a full retaliatory response” against Russia in the event of a single Soviet missile being launched from Cuba (Ellsberg himself had written the code book for such a US response only 18 months earlier and thus knew first-hand the horrors it would unleash) – but the central revelation here, the thing that will shock most readers as badly as it initially did Ellsberg, deals with chain of command.

The standard picture of that chain of command, when it comes to American nuclear weapons, is startlingly simple: the president makes the call. To this end he’s never physically far from “the football” – a briefcase containing nuclear codes and electronic equipment necessary to order a launch. For half-a-century, the public understanding has been, as Ellsberg puts it, “that there was no pre-delegation of authority, that only the president could legitimately make the decision whether or not to go to nuclear war, and that he must make that determination personally at the moment of decision.”

The assumption of such an arrangement was, in part, that a nuclear first strike being launched against the US would happen too fast for Congressional deliberation – missiles would strike the mainland in less than half-an-hour, and the life of the nation would depend on quick retaliation.

It has always been a bizarre arrangement – the president controls nothing else so personally that’s so important – but contains some comfort: it is the worst decision any American could make, but at least only one American can make it.

The most alarming contention in The Doomsday Machine though is that this arrangement is not really true and never has been – that it realistically couldn't have been, considering what a single sniper's bullet could do, or even a mishap that separates the chief executive from "the football". Ellsberg's most jolting contention is that nuclear authorisation has always been possessed by both commanders in the field and officials outside of Washington, DC – any one of whom could react to urgent incoming information (accurate or not) by ordering a nuclear attack without consulting with the president. Suddenly instead of one cause to worry, there are dozens of causes to be concerned about.

But still mainly one cause. In mid-November, for the first time in the decades since Ellsberg copied these nuclear secrets, this whole question came vividly back into the headlines when a US Senate Committee on Foreign Relations openly discussed the wisdom of relegating the power to launch nuclear weapons solely to the president (Donald Trump), who was characterised as “unstable” and “erratic”. As Massachusetts senator Ed Markey commented, “Donald Trump can launch nuclear codes just as easily as he can use his Twitter account.”

It’s a danger even darker than was Vietnam, and once again it is Daniel Ellsberg sounding the alarm.

___________________

Read more:

[ Book review: Nicola Pugliese's Malacqua reflects the political unrest of the time ]

[ Book review: Delving into the sad world of W N P Barbellion through his compelling diary ]

[ Book review: in 'Heather, the Totality Evil' stalks an ingenue, to crush a ‘perfect’ world ]

___________________