Do crickets, fish and chicken think, feel, and suffer? If they do, should we then apply the same criterion that most cultures apply with their refusal to consume dogs and cats, animals that we know as pets that are intelligent, loving creatures? That’s why Westerners don’t eat them – although other cultures, with other feelings about pets, do. Where does one draw the line?

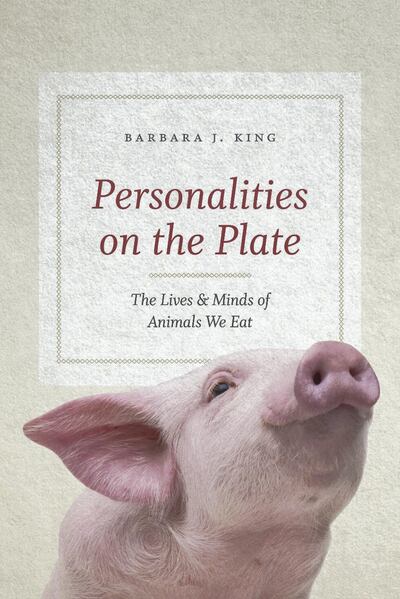

This is the involved ethical question posed by Barbara J King, a long-time American anthropologist who has been vegetarian for five years, even though she's worked in the field with animals her entire life. Personalities on the Plate is part memoir, part personal investigation into the research and findings of scientists on the topic of animal intelligence, and what it means for our societies and diets.

She argues – not entirely convincingly, I feel – that the "sentience" of animals, namely their ability to feel, perceive, or subjectively experience, dictates that we, as beings endowed with sophisticated critical intelligence and compassion, recognise the animal kingdom as fellow beings and refrain from slaughtering them for gastronomic enjoyment – in developed countries meat isn't necessary for nutrition or a healthy diet, but eaten because it tastes good. Animals that we have long thought of simply as food are more sophisticated than we had ever imagined, as a host of new research proves. Thus, if not cats and dogs, then not octopus and cows.

“It’s these highly developed brains of ours that enable us uniquely to look at the world with fresh understanding of and empathy for other sentient beings,” King concludes. “All animals – how they live naturally and how we force them to live and die when we make them into food animals – deserve our full attention when we decide who to eat.”

Cutting back on meat

Also for about five years, I too have been a been a vegetarian, though by no means an orthodox one. I'm willing to cheat when it comes to spicy salami and artichoke pizza and most fish dishes (the likes of such behaviour King rightly excoriates as weak-willed hypocrisy.) Unlike the author, the personalities of food animals did not play much of a role in my decision to circumvent meat as much as possible.

Actually, I’m a climate- change vegetarian, having turned to a non-red-meat and low-dairy diet in light of the overwhelming evidence that livestock cultivation is a major cause of greenhouse gases. I don’t imagine that my eating with a smaller carbon footprint changes anything in the big picture, but rather I feel that we, the current occupants of this planet, have to devise smarter ways of living so that future generations can enjoy (something close to) the high standard of living that we in the developed world have, until now, had. We can start redesigning from the bottom, namely starting with ourselves.

And, indeed, I’ve discovered that one can cut back on meat, dairy, and fish, as well as exotic imported foods, without suffering terribly. In fact, there is a cornucopia of tasty vegetarian dishes made with local ingredients that are every bit as delectable as meat dishes, one just has to find and try them. If only my colleagues didn’t once a week insist on this pizza place for lunch!

Moreover, as I’ve read up on industrial-scale meat production, other factors have strengthened my resolve, such as the atrocious breeding conditions of poultry and other livestock in farms involved in the mass production of meat. Also, I eat around those fish that are overfished but, until now, not those that are farmed. The more I read – and King’s book includes a host of excellent reading tips – the more I become rigorous in my commitment to seriously go veggie, or maybe even eventually vegan. Whatever the case, it will be gradual, as the arguments for it accrue.

This is why I dove into King’s book with such great relish, and ended up a bit disappointed.

The final verdict

She provides a wealth of evidence that almost all of the animals that people around the globe eat are more our peers than we suspected. Insects, for example, which are eaten in many places in the world – from taranchalas to crickets, learn, communicate, and make thoughtful decisions, King discovers, although she's not prepared to go quite as far as endow bugs with sentience. Much of their reactions are innate. So the insect world is a grey zone for her: animal life is animal life to hard-core veggies, but on the other hand if "thinking -feeling" is the bar, then insects don't quite cut it – and they possess a lot of protein too.

But the author definitely draws a line at octopus and fish, which her perusal of the existing literature and interviews with experts convinced her deserve more respect than to be thoughtlessly fried up or thrown onto hockey rinks to die, as apparently octopuses are in Detroit, a tradition of the city's team, the Red Wings.

Octopuses are the world’s most intelligent vertebrate, King concludes, able to see far enough in the future to carry coconut shells with them to use as shelter at a later point. They have brains that enable them to gather information in many ways, and thus to change colour, shape, texture, and pattern accordingly.

________________________

Read more:

The top retreats for vegetarians and vegans

Why more people are turning towards vegan beauty products

How veganism can save the planet

Vegan places to eat in the UAE

________________________

These are just the tip of the iceberg of octopuses' intelligent behaviour and as King moves up the hierarchy to chimpanzees at the end, one is convinced that there's a lot more to our favourite dishes than we thought.

But why exactly this should stop us eating them, I couldn't rightly ascertain. We know now that plants and trees have intellectual capacities too, so why draw the line at crickets, simply because they're dumber than chickens? Although I hadn't read the vast literature that she has, I nevertheless assumed much of this to be the case, lifetime fan of Watership Down that I am.

Also, the book's tone often got on my nerves. There are too many personal anecdotes and "fun facts" about animal behaviour and the world's array of quirky eating cultures. The author also throws in a bunch of arguments in favour of vegetarianism that are tangential to her own argument. Some of these, such as the research and literature on fish farming, made more of an impact on me than her main lines of argumentation.

And although she’s read all the important books and articles, it’s a mystery to me why she doesn’t bring Morrissey in, the pop cultural sage on the issue. “Meat is Murder” could be the book’s soundtrack.

But the point of the book is to make us think, King says. I’ll try to the next time I eat spicy salami pizza and see what happens. Maybe it will nudge me onto the path of orthodox vegetarianism, and I’ll be thankful.