For most of the 20th century, a fairly stable pattern developed in the publishing industry. The system was a sequence of barriers prospective authors had to surmount before their books could ever see the light of day. The author did the hardest part first: writing the actual book, taking months and sometimes years of blood, sweat and toil in the unswerving belief that they were doing something worthwhile. Once that part was finally finished, these writers had to get the attention of an agent willing to work on their behalf. This too was an arduous task necessitating mind-boggling persistence and a blizzard of rejections. In a tiny minority of cases, an agent would be found and the manuscript would later get shopped around to publishers. And a tiny fraction of those manuscripts would then get bought - usually on minimal terms, because each of those publishing houses doing the buying was groaning under the burden of paying disproportionately enormous advances to their big-name stars. Those lucky debut authors would have a modest payday and the thrill of seeing their work in print, but would face the prospect of slowly building a following through bookseller and reader word of mouth.

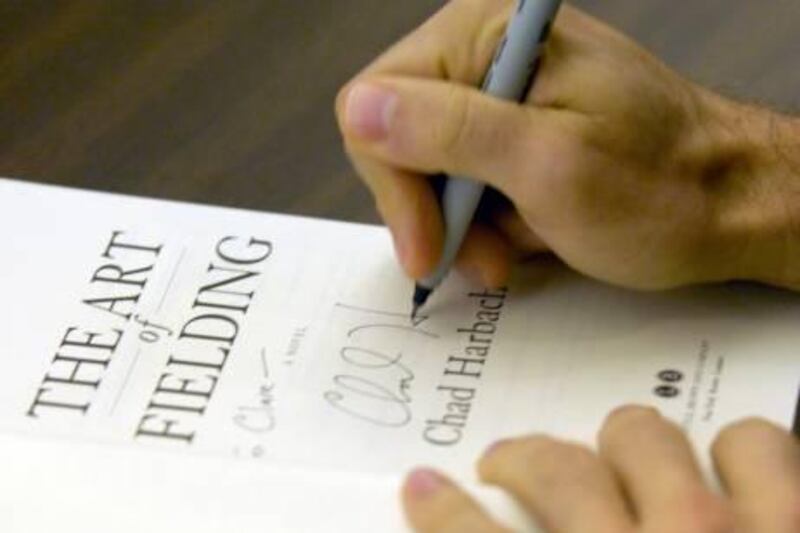

The system allowed room for meteors, of course. The most famous of these in recent months was Chad Harbach, whose debut novel The Art of Fielding, which will be reviewed in these pages next week, garnered such great advance word from agents that he was offered an astronomical advance (rumoured to be more than $1 million when the paperback rights were figured in, a staggering sum in the middle of a nationwide economic depression), although even this meteor had a little help, since Harbach was an editor at the trendy literary journal n + 1 and so had already made industry contacts undreamed of by mere mortals.

But such cases have always been rare, and in the 20th century they did little to disturb the pattern that had calcified: write a book, work hard to get an agent, pay that agent a fee and a percentage of your future sales, wait for that agent to get you a publishing deal, and in the lucky event that happens, hope your publisher is willing (or able) to promote your book during the limited window in which it is new.

In 2011, that pattern began to shatter.

There had perforce always been a second route to seeing your book as a physical, printed object: self-publishing through the often accurately named "vanity presses" was the poor relation to traditional publishing all through the 20th century. The many, many writers who weren't willing to endure the slog of finding an agent or hoping a publisher would treat them well, had the option to reverse the process and pay to have their work printed and bound. Vanity presses pocketed a hefty fee, gave their clients the satisfaction of holding their book in their hands (and inflicting a copy on every last living relative in their family tree), and, of course, entertained not the faintest idea of making that book competitive in the marketplace. Indeed, resorting to a vanity press was a tacit admission by all concerned that the book couldn't compete in the open marketplace; an unsavoury aura of desperate pride lingered about the whole endeavour, despite scattered examples of self-published books that then went on to become successes (James Redfield's The Celestine Prophecy and Irma Rombauer's The Joy of Cooking being two of the more lucrative cases).

Traditional publishers and vanity presses had one controlling element in common: they operated printing presses - they had the physical means to produce copies of the author's book. And agents had a controlling element as well: they had experience in telling the wheat from the chaff. It was a fixed system of vetting, and it seemed as permanent as the white cliffs of Dover. But it was utterly dependent on those two controlling elements.

The proliferation of individual access to the internet in the last decade ("I don't have a personal computer" was something you might hear without surprise as late as 1995 - in 2011, it would be so inconceivable as to be outright suspicious) has removed the exclusivity of those publisher printing presses - print-on-demand and subsidy printing services have proliferated in the wake of the digital revolution. Not only are these services far more affordable and user-responsive than ever before, but they're also far more competitive: the author's fee no longer gets him a couple of boxes of hand-stamped hardcovers - it gets him an ISBN, a wide choice of format and cover design, a listing with the world's biggest online bookstores, and output through large book distributors, too.

Suddenly, in the 21st century, an increasing number of would-be authors faced two alternatives: beg and dream of graduating from a traditional publisher's infamous "slush pile", or take the whole process into their own hands and start today. New book-producing services didn't say, "If we deem you worthy, we'll print your book and market it to the public", they said, "If you pay us, we'll print your book - and you can handle the rest as you see fit."

The last obstacle was that distasteful aura hanging around self-publishing, but a decade of Britain's Got Talent and American Idol and pervasive dissemination of blog culture have all but dispensed with it, for good or ill. The proliferation of social media websites has given new authors the means to do their own book-promoting, often with far greater accuracy - and results - than buying a box ad in Publisher's Weekly. Surely the greatest extant example of this is American author Amanda Hocking, who began self-publishing her teen adventure novels in 2010 and quickly earned more than $2m in sales without ever going near an agent or a traditional publishing house (they subsequently came to her; in a move that seems bizarrely anti-climactic, Switched, her next book, will be published by Pan Macmillan and will be reviewed in these pages next month).

And she's joined by a steadily increasing number of similar examples, some of considerably greater literary value: Sergio De La Pava's weird, brilliant novel A Naked Singularity, for instance, which was self-published and self-promoted in 2008, caught the notice of a handful of early reviewers, grew in word of mouth renown, and will be published by the University of Chicago Press next year.

Despite such examples, 2011's publishing landscape still looked very similar to 2010's in general. The latest works from such heavyweight, established authors as Julian Barnes, Haruki Murakami, William Kennedy and Don DeLillo came out alongside debuts by writers like Harbach, Erin Morgenstern (The Night Circus), Teju Cole (Open City), and Tea Obreht (The Tiger's Wife). Authors who'd previously published either solo or with small houses - fantasy author Michael J Sullivan, for instance, or indie fan favourite Tao Lin - "graduated" to bigger venues and broader exposure.

But possible fault lines were visible: American film director John Sayles' enormous new novel A Moment in the Sun was published not by a traditional house but by McSweeney's, an operation less than 15 years old - in large part because Sayles preferred their production values and audience-targeting to the treatment he was likely to get at the more established publishers he'd dealt with in the past. In order to compete in the new book-publishing world of the 21st century, those traditional publishers need to be nimble-footed in exactly the areas where they have always been the most elephantine.

Those areas all revolve around fitting the product to the customer instead of telling the customer to like the product, and 2011 is clearly the last year any major publisher will be able to refuse to do that. Publisher's Weekly notes that sales of electronic books in the US market increased five per cent in a matter of months between 2010 and 2011 - and sales of the expanding number of gadgets that read those books have skyrocketed in the same interval. Amazon.com reported that its sales of e-books in 2011 exceeded its sales of printed books for the first time, and that trend will not reverse.

These two converging patterns - authors producing and marketing their own books and readers utilising portable devices that put them directly in touch with those authors - have the potential to rewrite the entire equation that previously governed the publishing industry. In fact, they have the potential to eliminate that industry altogether.

The old way - raze a forest to produce huge shipments of a new printed title, send them to bookstores in numbers generated by often antiquated metrics, then take returns of sometimes as much as 80 per cent of those initial shipments, at costs the publisher must absorb because the whopping flat-advance they paid to the blundering-titan author (figures like Tom Clancy or John Grisham, both of whose latest print releases failed to meet sales projections) was negotiated by their agents to be non-contingent on actual sales - that old way was venal and purblind even when there was no viable alternative.

In 2011, a viable alternative was truly born: publish yourself, market yourself, sell your book directly to your audience, and, if you hook that audience, reap the rewards directly - no percentage to your agent, no kowtowing to your publisher, nothing of the extremely limited shelf-life associated with bookstores or archaic return windows. The main thing missing from the new equation is the prestige factor associated with traditional publishing houses, and the 21st century readers consuming e-books on their tablets don't care about that prestige any more than they do the atmosphere on Neptune. They just want to read stuff they like (and, not unimportantly, pay a lot less to do so). Publishers that don't adapt to these new realities in 2012 won't be around to adapt to anything in 2022 - and the world of books will be better off without them.

Steve Donoghue is managing editor of Open Letters Monthly.