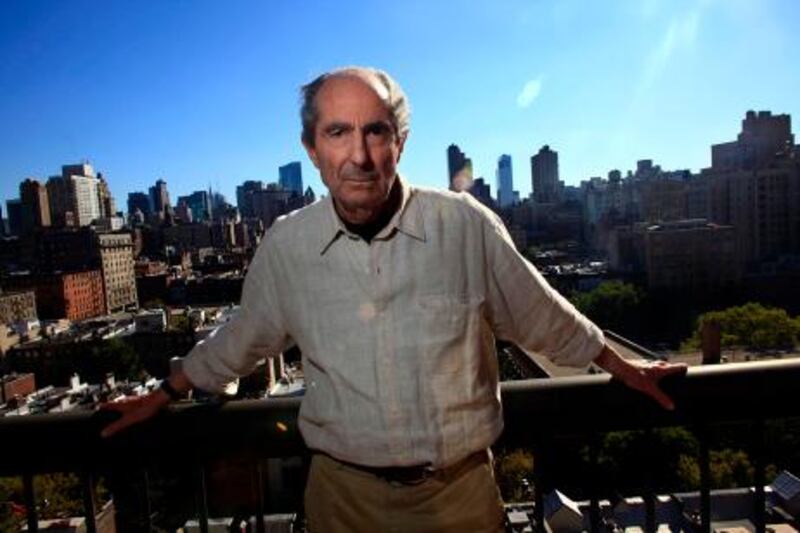

If it's possible to judge the worth of a literary award by how much controversy it causes, then the Man Booker International Prize 2011 must now be one of the most prestigious. Last month, one of the nominees, John Le Carré, sensationally withdrew from the running. Last week, one of the judges for the £60,000 (Dh356,000) prize, which honours a living writer's entire canon rather than a specific book, quit the panel in disgust. Carmen Callil was furious that the American author of The Human Stain and Portnoy's Complaint, Philip Roth, was announced as the winner. And the outspoken author and founder of feminist publisher Virago, quit in grand style.

"I don't rate him as a writer at all," she told The Guardian. "He goes on and on and on about the same subject in almost every single book ... in 20 years' time will anyone read him?"

It's fair to say, then, that Callil didn't agree with the decision. But she might have known that the chairman of judges, Rick Gekoski, would get his way. When Le Carré complained that he didn't compete for literary prizes, Gekoski respectfully declined his request not to be considered. Back in 2005, Gekoski was on a divided panel for the annual Booker Prize - his unwavering support for John Banville's The Seaforcing a decision based on the chairman John Sutherland's casting vote. Banville won.

Callil's complaints gave us an interesting insight into the workings of a literary judging panel. She suggested that Gekoski and Justin Cartwright's passionate support of Roth - he "goes to the core of their beings", she sniffed - had simply overruled her misgivings. "You can't be asked to judge, and then not judge," she said. Even Gekoski admitted at the Sydney Writers Festival that "three was a very dangerous number, a hard number to come to a decision".

But judging panel disagreements do make for great sport. On the most populist level, most of the drama on television talent shows such as The X Factor or Strictly Come Dancing doesn't lie in the performance of the acts. It's the catty put-downs and barbed comments from the judges that create the tension. Sadly, television audiences won't get to experience what Gekoski called the "considerable amount of argument" that took place during their deliberations earlier this month. But it's no surprise their fallout was made public afterwards - not least because, for some judges, differences of opinion appear to be part of the fun.

When I spoke to the broadcaster Andrew Neil, chairman of judges for the Costa Prize earlier this year, there was a definite twinkle in his eye when he admitted that there had been a "robust argument" among the jurors about whether to reward Jo Shapcott's book of poetry, Of Mutability, or Maggie O'Farrell's novel The Hand That First Held Mine. In the end, the prize went to the poet, but not before "a lot of anguish". Secretly, I think he loved the debate.

Neil admitted that it hadn't been a unanimous decision - and they rarely are in such prizes. But usually the dissenters are at least happy for the winner - and don't make their distaste for the decision as public as Callil. Usually. The Man Booker Prize is so proud of its "first controversy" in 1971, that it recounts it on its website. One of the judges, Malcolm Muggeridge, withdrew from the panel (before the winner had been announced), saying he was "nauseated and appalled" by the standard of submissions. Time has not been kind to his decision: the shortlist included Doris Lessing and VS Naipaul - who would both go on to be awarded the Nobel Prize for Literature (incidentally, the one award Philip Roth would, it is said, rather like).

The Booker's history is pockmarked with oversensitive judges prone to something of a flounce if things don't go their way. Nicholas Mosley should perhaps have learnt from Muggeridge's experience before resigning from the 1991 panel despairing of a shortlist that included Ben Okri's magical African odyssey Famished Road. He's since admitted that he resigned in a huff and that Okri's book was beautifully written. But for proper childish foot-stamping antics, it's difficult to see past the 1977 chairman Philip Larkin, who was perhaps being a little extreme when he threatened to jump out of the window if Paul Scott's Staying On didn't win. Thankfully for all involved, it did.

But read the thoughts of any judge in any year of the Booker, and they're basically the same: they go to the meetings with their favoured book, and no amount of discussion will change their view. As John Sutherland said at the launch of the 2005 prize: "At the beginning you have a very civilised conversation and everybody likes each other. Then there's the longlist, and there's friction and heat. Tempers begin to fray, and then there's battle, head to head. After that there's the shortlist and people walk out and so forth. So it goes from civilised conversation to world federation wrestling match. Finally you are locked away like cardinals in enclave and in the end the smoke comes out."

Often, this means that the winners of cultural prizes decided by committee are often the works that the judges hate the least rather than love the most. Potter Grayson Perry was the rank outsider to win the 2003 Turner Prize, but it is said that the panel was so split by whether to reward Jake and Dinos Chapman's sculpture or Willie Doherty's video installation that, in the end, all agreed on Perry's likeable entry.

Still, at least they came to a decision of sorts - and in hindsight it was the right one. Pulitzer Prize judges have failed to agree on an award-winner a staggering 25 times, which means, rather amusingly, they just don't name one at all.

Most recently, there was no award in the Breaking News category this year: rather disappointing for the nominees who are now more famous for being not quite good enough.

For those who think judging panels are a case of too many cooks, here's a salutary lesson from Australia. The prestigious Sulman Art Prize has just one judge - which, on the surface at least, would appear to preclude any argument or controversy. The problem is, this year's judge, the artist Richard Bell, couldn't make up his mind. So he tossed a coin on to a table filled with the names of the artists in contention.

And the name the coin landed on, Peter Smeeth, won. Bell justified his action to the Sydney Morning Herald by arguing that "every prize is a lottery", but unfortunately even the winner didn't appreciate his methods.

"It takes away from my credibility," said Smeeth last month in the Herald. "It is a bit deflating, from my point of view, if that's the whole basis for how I won the prize. I certainly would like to think I won it on merit, not on the toss of a coin."

So maybe Callil should have insisted on a game of rock-paper-scissors to decide the Man International Booker Prize. That might have lightened the mood a little ... and really got on Philip Roth's nerves.