Roger Allen is looking very pleased. As well he might; last week, on Monday, he picked up the Saif Ghobash-Banipal Prize for Arabic Literary Translation at a prestigious awards ceremony in London. But typically, that's not the reason for his delight. He's just finished chairing a masterclass on Arabic literary translation and is deeply encouraged by the young people from all sorts of backgrounds and nationalities who attended. "When I started translating in the late 1960s, that just wasn't the case," he says, beaming.

They come to listen to Allen because he is the pre-eminent translator/expert of modern Arabic literature, perhaps most recognised for bringing the work of the only Arab writer to win the Nobel Prize for Literature, Naguib Mahfouz, to an anglophone audience.

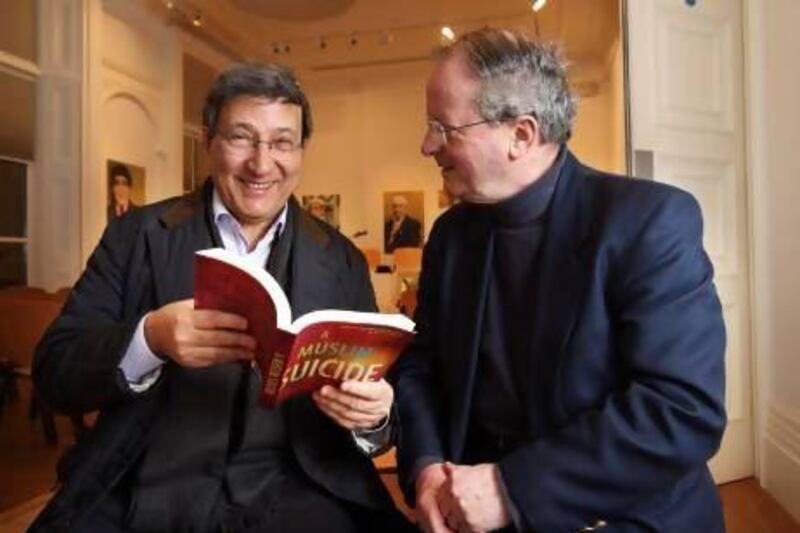

More recently, he's struck up a fruitful relationship with the Moroccan writer Bensalem Himmich, and the book for which Allen won the 2013 award (sponsored by Omar Saif Ghobash and his family in memory of Ghobash's late father, the UAE's first Minister of State for Foreign Affairs) reveals Allen at the height of his powers. After all, Himmich's A Muslim Suicide - entitled The Man From Andalucia when it was longlisted for the International Prize For Arabic Fiction in 2009 - is by no means a straightforward translation.

Himmich's book is an exploration of the life of one of Islam's most radical thinkers, the 13th century Sufi liberal philosopher Ibn Sab'in. He bends Sab'in's mysticism and beliefs into a tragic narrative which takes the persecuted Sab'in from Muslim Spain, via Algeria to Cairo and finally Mecca at the time of the Crusades and Mongols. When even the quote on the back of the book warns "the reader must tease the significance out, often with great effort", you know this is a serious undertaking.

"It was incredibly difficult to translate," admits Allen. "Not because Bensalem is a problematic writer - far from it - but because he's such an erudite scholar and he replicates Sufi mystical thought, which operates on many different levels. He knows this time better than most as a professor of philosophy and history, so he can use all his knowledge and then weave in his imagination. There was one time where I asked him where he'd got this religious group called the 'earth worshippers' from. I couldn't find reference to them anywhere, you see. He told me he'd made them up!"

Himmich laughs at the anecdote, but behind it there's a serious point. Though A Muslim Suicide will inevitably be filed under historical fiction, he's uncomfortable with the genre tag and the restrictions it implies.

"The history is just the pretext, for me," he says. "That's not to say you don't have to know as much as you can about these people, but history is about ideas, whereas I want to describe a human life and story."

Where the line can and should be crossed into fiction when writing novels about the past, has exercised writers for years - and later, at a public event celebrating the prize at London's Mosaic Rooms, Himmich is asked whether, when he writes about marginalised characters, his first responsibility is to the truth.

"Look, Shakespeare wrote about supposedly real characters and situations, didn't he? But no one complains about his approach, and that's simply because he put emotion at the centre of his stories. And I consider the past in exactly the same way as I look at the present. I've written about extraordinary rendition in My Tormentor [which Allen has already translated; it awaits a publisher]. In 10 years' time, that will also be historical fiction, won't it?"

Himmich is right, of course, and it's a relief that he gets so animated about his role and duty to character and narrative as a novelist - it makes A Muslim Suicide much less daunting than the cover makes out. In fact, the Spain he describes at the start of the book, where Sab'in begins his journey, feels modern, cosmopolitan and completely recognisable.

"Exactly," says Allen. "That's what's so clever about it. Sab'in faces an unhealthy linkage between extreme religious orthodoxy and politics throughout his life. That's not something only relevant to the 13th century, is it? And to me, that has been a trend in Arabic novels since I started translating them in the late 1960s. Since then, authors - such as the Egyptian Gamal El-Ghitani - have consistently used history to ask questions of what it meant to be Arab."

Having such a broad and rich background and interest in Arabic writing makes Allen indispensable. Along with Humphrey Davies, the runner-up in the prize for his translation of I Was Born There, I Was Born Here by Mourid Barghouti, he's bringing not just his skills to bear on the translations, but a deep understanding of the progression of modern Arabic literature. What's more encouraging is that both men do so without "westernising" the texts.

"I told the students this morning that it's not the job of a translator to make these books accessible to a western audience," says Allen. "To me, the reader has to confront difference - maybe even difficulty - and foreignness. In a way, that's the joy of reading books in translation."

Find out more about the prize at www.banipal.co.uk