The images in Arab Photography Now offer a glimpse of the modern Middle East, fragments of the themes that preoccupy the artists of the Arab world and, by extension, their societies. The images span a range of countries, but gather their influences from even further afield. They reach across space and time, drawing on experiences from history and the modern. Yet what is fascinating in these works is how often the same themes come up and, in particular, war.

Wars to dominate, reshape and remake the Middle East have scarred the landscape of the region and their effects are documented by these artists.

Here are the impersonal watchtowers of Israel, guarding an occupation without end, by Taysir Batniji, stark symbols of a relentless encroachment that have seen even the artist himself exiled. Here are Jananne Al Ani's images of the Iraqi desert from the air, into which have been carved defensive positions. Here also are abandoned military vehicles that scar modern Lebanon, photographed by Khalil Joreige and Joana Hadjithomas.

Perhaps the most shocking works in the book come from Farah Nosh, who, noticing how rarely the media focused on those Iraqis who were bearing the brunt of the effects of the 2003 invasion, set about trying to document these victims.

In her photographs, the true horror of the invasion becomes apparent - men and women, young and old, with lost limbs and awful injuries. Nosh often juxtaposes these adults with young children, a representation of how the invasion will be felt across the generations. In one haunting photograph, a young girl stands next to her father, his right arm and right leg both amputated. She grips his prosthetic leg tightly.

Jehad Nga tackles the young American men who make up this military. He shows them in private moments, frightened and pensive, in a world far from home. There is a curious symmetry between these images and Nermine Hamman's photographs of the young soldiers of Egypt, guarding the protesters who ousted Hosni Mubarak at the start of last year. Here, too, are young men, far from home, in a world they can scarcely imagine. Like the American soldiers in Iraq, they come from small towns, scarcely able to comprehend the history they are creating.

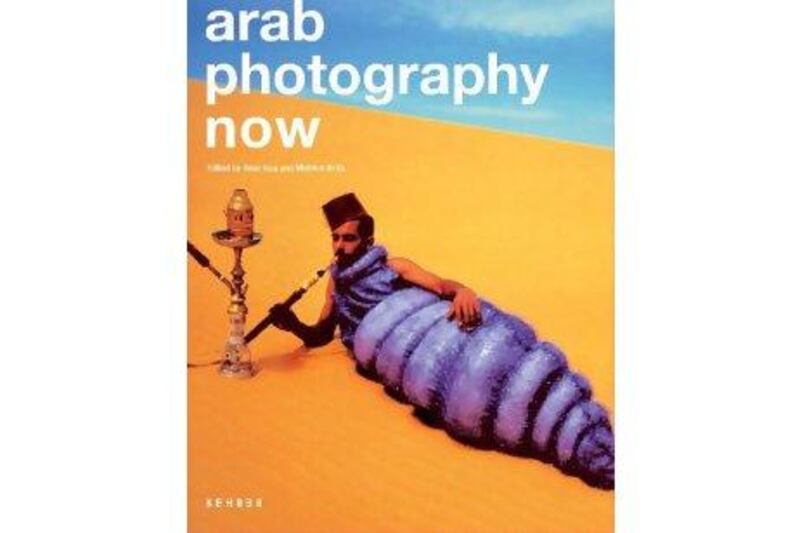

Reclaiming the narrative is also important to many of these artists. The intense focus on the Arab world by the west over the past two centuries, the intense fascination European neighbours have for these civilisations, has resulted in a flood, not only of images, but also a framework of ideas. For Arab artists, dismantling this framework, overlaying it with their own reality, has always been an important task.

In the past, western conceptions of the Arab world in Orientalist paintings reflected the twin poles of power and sexuality. Here, in modern photographs, these fantasy objects still exist - see how Majida Khattari takes the imagery of Orientalist paintings and recasts them with modern models and symbols.

It is in these symbols that the continuation of essentialising the Middle East through fragments can be seen: in the past, odalisques represented the western conception of Muslim women; today that symbol is the veil.

One of the best practitioners of this subversion is Lalla Essaydi: her extraordinary re-imagining of the harem highlights how far previous portrayals of the east were to do with the sexual fantasies of western artists, how little to do with the real lives of women.

A third theme is fantasy, the making and unmaking of dreams. Nabil Boutros' photographs of Egypt explore the fantasy of modernity, how Egypt is searching for modernity in buildings and public spaces. Kader Attia looks at the burden of dreams on the dispossessed of the Arab world, documenting the young Algerians dreaming of a life in Europe.

Probably the best fantastical works in the collection come from Lara Baladi, enormous collages full of fairytale characters, places where dreams meet reality, so that it is often unclear if the figures depicted are representations or fantasy. Her figures appear from the sea and from the sand, forcing the viewer to question whether they are from these places or merely passing through. The Middle East has long been a place where the two blur: the tragedy of the region is that often the fantastical appearance of figures on the horizon, figures from another world, is not merely dreamlike, but nightmarish.

Faisal Al Yafai is a columnist for The National.