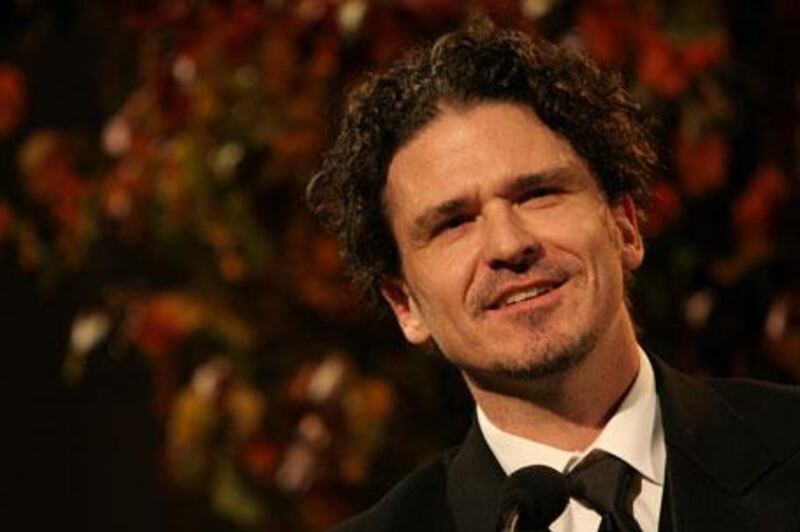

Dave Eggers, Michael Chabon and Jonathan Safran Foer, three of America's most feted contemporary novelists, are each releasing a non-fiction book this month, cementing a trend that's been gathering momentum over the past decade. While travelogues and biographies have been a literary staple for centuries, popular science, history and current-affairs books have only really exploded as bestsellers during the Noughties. The fact that this trio of ultra-hip, prize-winning authors is getting involved proves that factual books about contemporary issues can be both entertaining enough to read on the beach, and stuffed with literary merit. And they might even make a case for changing the way you live.

Although Eggers has been concentrating on fiction recently (his superhuman schedule has recently included two screenplays, Where the Wild Things are and Away We Go, both released in 2009), writing about real life isn't new to him. His debut, the Pulitzer-shortlisted A Heartbreaking Work of Staggering Genius, combined his memories with stylised flights of fancy, and his 2006 novel What Is the What drew heavily on the experiences of the Sudanese refugee Valentino Achak Deng.

Zeitoun, which is published on March 25, is the first sustained piece of non-fiction Eggers has penned solo since A Heartbreaking Work of Staggering Genius (in the meantime he has co-authored books on teaching and on Americans wrongfully convicted of crime). It tells the story of Kathy and Abdulrahman Zeitoun, a married couple with four kids, who run a building and repairs company in New Orleans. (Because of his unwieldy first name, Abdulrahman is known to friends and neighbours simply as Zeitoun.) While Kathy and the children flee the city as Hurricane Katrina looms, Zeitoun stays to look after their family home and ends up camping on the roof, paddling around on a canoe to help stranded survivors.

But as looting and lawlessness break out, the Syrian-born, Muslim family man becomes a target for overzealous policing, and miscarriages of justice mount up to wreak disaster on him. Like Chabon's and Safran Foer's books, Zeitoun is written with a lightness of touch that belies its heavy subject matter. Eggers writes from the alternating perspectives of Kathy and Zeitoun, adding details about their dreams, the smells of their daughters' bedrooms and detailed dialogue in a way that's more novelistic than journalistic. The structure, too, is borrowed from fiction: Zeitoun's Syrian boyhood is recalled in a series of flashbacks, while the rest of the book's events are told chronologically, from the day the hurricane hit to the months following it.

Eggers's prose is simple, straightforward and characteristically upbeat, but as the book nears its end, a moral message emerges about the dangers of police profiling, human rights abuses relating to terror suspects in the United States and the government's disorganised response to the disaster. Images of the overcrowded and chaotic Superdome stadium are familiar from news reports, but by introducing a hardworking American family and telling their story, Zeitoun prompts readers to see these issues from a fresh perspective. Proceeds from the book are being allocated to the Zeitoun Foundation, which funds rebuilding schemes in New Orleans as well as projects promoting human rights.

In this way, telling stories becomes a form of activism for Eggers; Safran Foer pulls off the same trick in Eating Animals (which was released in the UK on Thursday), his first work of nonfiction. Safran Foer is best known for the award-winning Everything Is Illuminated, which was turned into a movie starring Elijah Wood in 2005, and was followed by the post-September-11 story Extremely Loud and Incredibly Close.

Eating Animals tells the story of the author's commitment to vegetarianism on becoming a father, after a lifetime of see-sawing between eating and avoiding meat. During the course of the book, he combines his family history with accounts of breaking into a factory farm, well-researched facts and figures, philosophical thought experiments and his changing feelings on the emotional, social and ethical aspects of eating.

He kicks off by talking the reader through an inconsistency in the way that most people treat animals, pointing out that most omnivores irrationally put the rights of some animals over others. He gives the example of hot dogs being sold outside the enclosure of the world-famous polar bear cub Knut. If we gave our habits more thought, he says, we'd be as horrified by the idea of scoffing hot dogs as we would be at the idea of feasting on the cute little cub.

There are many reasons Safran Foer gives for why we should feel this horror. Many will be familiar: animal agriculture is the primary cause of climate change, making a 40 per cent greater contribution to global warming than all transport combined; factory farms are barbaric, unsanitary and wasteful; fishing methods are inefficient (for each pound of shrimp eaten, 26 pounds of additional fish are killed as "bycatch"), and so on.

As one might expect, there's the odd stomach-turning description of animal cruelty. Testimonials from slaughterhouse workers are particularly vivid, but Safran Foer doesn't try to shock his readers into submission. Combining research from journals and books with illicit midnight farm visits, interviews with farmers and other agriculture workers, and his personal experiences, he unsentimentally pieces together an argument for vegetarianism that's hard to refute.

To those who suggest that one person's actions don't make a difference, he reminds us that individuals have helped change the world by doing things as simple as refusing to switch seats on a bus. "Compassion is a muscle that gets stronger with use," he argues, "and the regular exercise of choosing kindness over cruelty would change us." Alongside these two books - one advocating greater protection for human rights, the other campaigning for better animal welfare - Chabon's Manhood for Amateurs, which was released on Thursday, seems to be a more personal, less political read. Subtitled "the pleasures and regrets of a husband, father and son", it's a series of essays on topics including Chabon's love for comics and baseball, his attempts to be a better father, his love for his wife, has relationships with parents and friends, the future of the human race, Barack Obama and his man-purse (or "murse").

It might seem that the appeal of this sort of quirky memoir would only extend as far as hard-core Chabon fans dying to know the man behind the Pulitzer Prize-winning The Amazing Adventures of Kavalier and Clay, Wonder Boys and the rest. But Chabon is a dazzling writer, and while the subject matter is limited to his experiences, arguments are made and conclusions reached that are much broader in their scope.

In analysing how boys and men are expected to act, for instance, he makes a case for reconsidering attitudes towards gender: he talks of "the subtle damage that is done repeatedly to boys who grow up learning from their fathers and the men around them the tragic lesson that failure is not a human constant but a kind of aberration of gender, a flaw in a man, to be concealed". He also speaks with pride of learning to cook as a small boy, and of buying himself a purse (not the manliest of accessories), while criticising superhero comics for forcing female characters into weak roles such as Invisible Girl and Shrinking Violet.

Another theme that runs throughout Manhood for Amateurs - and much of Chabon's work - is the vital need for imaginative escape. As he writes about his childhood compared to that of his children, he worries that overprotected kids growing up today aren't given enough space to carve out their own world. "Art is a form of exploration," he says, "of sailing off into the unknown alone, heading for those unmarked places on the map. If children are not permitted - not taught - to be adventurers and explorers as children, what will become of the world of adventure, of stories, of literature itself?"

The benefit of art and pop culture, as he sees it, isn't just that they provide a healthy respite from the real world, it's that they also help us be better people. They "increase our sense of shared experience, of shared suffering, rapture, nostalgia, or disgust with our fellow humans, whose thoughts and emotions are otherwise locked away". To feel compassion, in other words, we need the imagination to put ourselves in another's shoes, which makes Eggers and Safran Foer, as well as Chabon, excellent candidates for championing causes we might otherwise forget. Escapism is always tempting in a recession, and it can do some good, but it's heartening that these storytellers are wrestling with important real-life issues, too. Let's just hope none of them abandons fiction for good.