On 9 December, 1933, not quite 19-year-old Anglo-Irish Patrick Leigh Fermor resolved to set off, on foot, from the Hook of Holland to Istanbul (or as he insisted on calling it, Constantinople). He was inspired by Robert Byron’s The Station, and was given the knapsack that accompanied its author to Mount Athos. Into it he packed pencils, notebooks, a volume of Horace and The Oxford Book of English Verse. With a monthly allowance of £5 (Dh29), he lived frugally, sleeping in haystacks and hostels, dosshouses and schlosses as he made his way “south-east through the snow into Germany, then up the Rhine and eastward down the Danube … in Hungary I borrowed a horse, then plunged into Transylvania; from Romania, on into Bulgaria”. On New Year’s Eve, 1934, he crossed the Turkish border at Adrianople and reached Istanbul.

A Time of Gifts (1977) was his first published account of that journey and Between the Woods and the Water followed in 1986, but still he had only reached the Iron Gates, which form part of the boundary between Romania and Serbia. Both works have a Proustian quality. Written by a man in middle age recalling his journey as an 18-year-old, he captures the meaning, value and excitement of travel, combining the romance of youth with the knowledge and wisdom gathered over the following decades. They can be counted, not just in the literature of travel, but in the canon of 20th-century English literature. His boundless curiosity, his infectious enthusiasm, his penchant for the arcane, his fondness for an anecdote, and his gift for language combined with a keen eye and a sharp ear produced some intoxicating prose.

For 27 years, his readers have clamoured for the last of the trilogy to complete that epic journey. And this month – an astonishing 80 years after he set out (and two years after his death) – this much longed-for third volume, The Broken Road, has, at last, appeared. The completion of the trilogy is, in its way, as much of an odyssey as the walk itself.

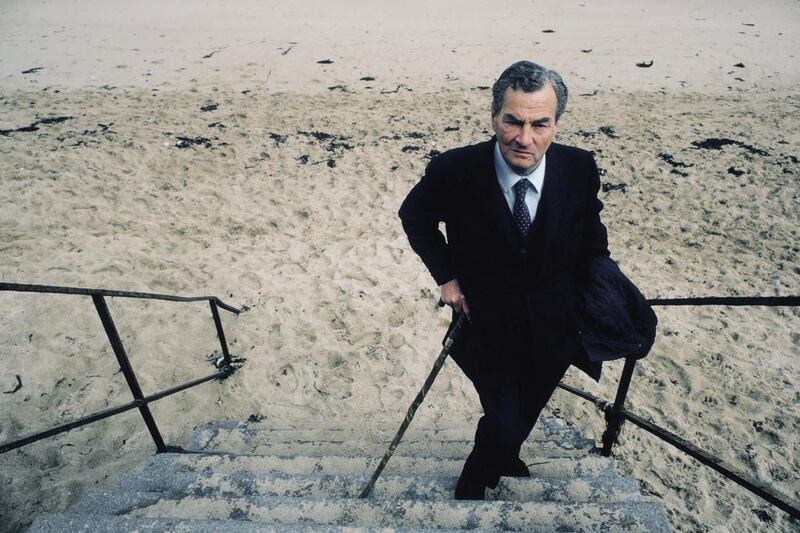

But first to the man himself. A child of the Raj, Patrick Leigh Fermor (always Paddy to his friends and fans) was born in London in early 1915, the only son of Sir Lewis Leigh Fermor, the sober, distant director of the Geological Survey of India. Aeileen, Paddy’s dramatic, erratic mother, was to her son the most inspiring and amusing figure in his life. She returned to India, leaving him for four years with a farmer’s family in Northamptonshire where he ran wild. He was expelled from most of his schools; the last, King’s School, Canterbury, for being seen holding hands on an upturned apple basket with a greengrocer’s daughter.

Footloose in London, after an affair with one of the Bright Young People, he developed a sudden loathing for the city and left for the continent. In Istanbul, 12 months and 21 days later, his journey was still not over. It was quite some gap year. In May 1935 he reached Athens where he met a Moldavian princess; and so began two great love affairs – with Balasha Cantacuzène and with Greece.

On the outbreak of war, he left his princess and returned to England and was soon assigned to the Special Operations Executive on German-occupied Crete. On the night of April 26, 1944, Paddy and a fellow officer, Billy Moss, impersonating German corporals, kidnapped General Heinrich Kreipe. The episode inspired the 1957 film, Ill Met by Moonlight.

In 1946 Paddy met Joan Eyres-Monsell, the clever, beautiful monied daughter of Viscount Monsell. She travelled with him to the Caribbean, which inspired his only novel, The Violins of Saint Jacques (1953). Joan waited until 1968 to marry him, by which time she had bought, and they had built, a remarkable house by the sea in the Mani, a remote corner of the Peloponnese. His Mani (1958) and Roumeli (1966) were a result of his travels by mule and on foot and together amount to a love letter to his adopted country.

Although Three Letters from the Andes appeared in 1991, the words that appeared to gush in a torrent from pen to page seemed to have dried up. So in 2003, as if to partly satiate his disciples, Artemis Cooper collected a lifetime of Fermor’s articles, extracts and reviews for Words of Mercury. As The Times Literary Supplement observed, he “combines the resourcefulness and daring of Odysseus with the learning, culture and glamour of a latter-day Byron”. Five years later, his sparkling correspondence with his friend of 60 years, Deborah, Duchess of Devonshire, the last of the Mitford sisters, was published as In Tearing Haste.

He remained at Mani until the day before his death in England in 2011, aged 96. There must have been some despair that the promise of the last line of Between the Woods and the Water ‘TO BE CONCLUDED’ had not been fulfilled. He would do anything to avoid it; once emerging triumphantly from his study to proclaim he had just translated PG Wodehouse’s Great Sermon Handicap into Greek. In 2008, Cooper, who had known him since childhood, found in the archives of Paddy’s publisher, John Murray, a manuscript of the last leg of what Paddy called his “Great Trudge”. It had been written in 1963 and 1964, curiously before the first two. He had it sent for and worked on it until a few months before his death. Paddy had joked it should be entitled The Carpathian Snail. This forms the bulk of The Broken Road and, while the perfectionist Paddy may have wanted to go on polishing it for decades more, its pages bear all the dazzling, richly layered detail and erudition that is classic Leigh Fermor.

Cooper, who published a superb biography of Paddy in 2012 and Colin Thubron, his literary executor, have, together, been responsible for this act of homage, noting reassuringly in their introduction, “There is scarcely a phrase here, let alone a sentence, that is not his.”

Setting off from the Iron Gates, he arrives at the great monastery of St John of Rila, describing “an archbishop and several bishops and archimandrites besides the abbot and his retinue. They officiated in copes as stiff and brilliant as beetles’ wings, and the higher clergy, coiffed with globular gold mitres the size of pumpkins and glistening with gems, leaned on crosiers topped with twin coiling snakes.” Later, as he heads for the Danube, he encounters “an indefinable presiding charm … of a party of itinerant beekeepers”.

This was a quality Paddy had in spades; as with the rest of his journey he always found somewhere to sleep – a consul here, a countess there; but a cowshed and a cave too. Another winning trait was that his boredom threshold was virtually non-existent. Friendships were forged instantly, but, given his quest, partings were inevitable and frequent. As he put it, “The whole itinerary was a chain of minor valedictions, more or less painful ones, seldom indifferent, only occasionally a relief.”

He was fascinated by history but disinterested in politics and was aghast and distressed when he learnt that a young Bulgarian companion thought he was a spy. “Races, language, what people were like, that was what I was after: churches, songs, books, what they wore and ate and looked like …”

There is an honesty and frankness in The Broken Road, not as apparent in the first two volumes.

He reveals bouts of depression and shares struggles with his memory. It has always been a mystery how he could possibly recall with all that astonishing detail after 30 years. All he had was one notebook, The Green Diary, saved and kept for him by his lover Balasha.

There is one brilliant set piece, of a night in a cave off the Black Sea with a group of fishermen and goatherders, which (from Cooper’s biography) was clearly a conflation of two episodes.

Asked in 2000 by the journalist James Owen if travel writers improve on truth for the sake of art, 85 year-old Paddy responded, “I’m a bit worried that I’ve got a slightly disinfectant memory, as if some goblin had washed out the gloomy parts and let the luminous ones survive. But, overall, I don’t think I’ve sinned too heinously.”

Although Paddy’s journey was to end in Constantinople, his Green Diary, which had recorded nothing more than impressionistic notes and jottings of his time in that city, became, on January 24, 1935, a fully written record of his next destination, Mount Athos, the holy heartland of Greece.

It seems appropriate to see in The Broken Road the last of this great Philhellene as he first fell for Greece, that other great love of his life. The other fascinating feature to this epic saga is that Paddy’s account of the original journey ends mid-sentence – at Burgas, only 75km and a few days’ walk from his goal, Constantinople, with “…. and yet, in another sense, although …” What a poignant and somehow fitting finale for a legendary procrastinator. It was certainly worth the wait.

Mark McGinness is a regular contributor to The National.