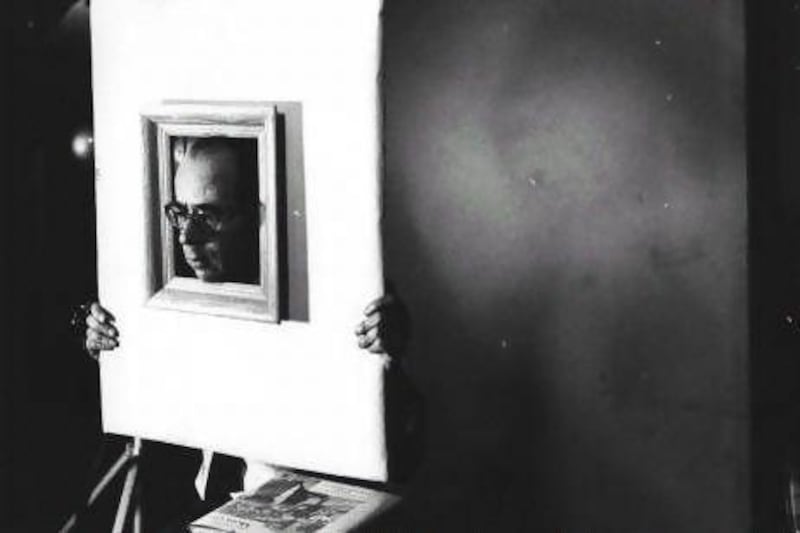

The photographer Philippe Halsman produced some of the 20th century’s most recognisable portraits – from his picture of the model Constance Ford against the US flag used in Elizabeth Arden’s Victory Red lipstick advertising campaign, to the celebrated “jump” photographs (from which Austin Ratner’s novel takes its title) that pictured screen sirens such as Audrey Hepburn and Marilyn Monroe off their guard, their skirts billowing around them, giggling like schoolgirls in mid-air.

The Latvian-born Jew’s rise to fame after he fled to the US during the Second World War is a fascinating enough story in its own right. He photographed Albert Einstein at Princeton University in 1947 – the famous image that appeared on the 1966 US postage stamp and the cover of Time magazine in 1999, when the physicist was named Person of the Century – his sad eyes reflecting the abysses of war, fully admitting his own culpability in delivering the atomic bomb into the hands of the politicians. Halsman’s works also include Dalí Atomicus featuring the surrealist painter, three black cats, a stream of water, an easel and a chair, all suspended above the floor; Winston Churchill defying despair in the face of a Europe in flames; and not to mention all the beautiful women, Bacall, Bardot, Bergman and the rest. This stage of Halsman’s life, however, is where Ratner draws his story to a close. It’s his less widely documented but perhaps even more incredible early years that the author has chosen as his subject.

On September 10, 1928 the then 22-year-old Philipp (this is before he adopted the French version of his name) Halsman was hiking in the Zillertal Valley, Tyrol, Austria, with his father Mordurch, a dentist known as Max who saw himself as quite a sportsman. By the end of the day the older man lay dead from serious head injuries and his son stood accused of murder. Halsman protested that he saw his father fall to his death but the injuries sustained by the dead man suggested a violent attack, and an incriminating blood and hair-covered rock was discovered among blood-soaked grass nearby in an otherwise apparently deserted area of the Alps.

These tragic events set in progress what Ratner describes as “an early chapter of the Holocaust that is now mostly forgotten in the English-speaking world”. Despite nothing but circumstantial evidence that the son had committed the crime, he was imprisoned in Innsbruck and tried twice (the pronouncement of the first trial was challenged) for patricide in a court and a country that was vehemently anti-Semitic.

Quotes from letters Halsman wrote to his sweetheart Ruth while in prison, transcripts from the trials and extracts from newspaper reports introduce each chapter, adding a layer of indisputable fact to Ratner’s otherwise self-confessedly fictionalised story. The author begins by declaring that his book is not a biography, instead it should be read as an artistic tribute to Philippe Halsman – more like a portrait or a sculpture.

Inspired by André Gide's statement that "fiction is history which might have taken place, and history is fiction which has taken place", Ratner explains that The Jump Artist is "based on a true story", combining the "known facts about Halsman's history" with "what might plausibly have been the case".

This makes for an intriguing mix of fact and fiction – an increasingly admired device given the rise in popularity in recent years of biographical novels such as Hilary Mantel's Man Booker prize-winning Wolf Hall and its recent sequel Bring Up the Bodies, or The Paris Wife, Paula McLain's fictionalised account of Ernest Hemingway's first wife, Hadley, that appeared last year.

When it comes to its narrative, The Jump Artist certainly holds its own alongside competitors in this field – Ratner has chosen his subject with care (though it should be noted that, technically, Joshua Sinclair got there first with his film Jump! in 2007, although it remains largely unheard of) and the story of the trial that lies at the heart of the book is absolutely gripping.

The horror of Halsman’s treatment at the hands of his captors is juxtaposed against a description of a trial that is so clearly prejudiced and unjust that it reads as near farcical in parts. The prosecution’s case is based on nothing but pure racial hatred – the mere fact that Halsman is Jewish is enough to ensure the alpine-dwelling locals take matters into their own hands, branding and interning him as a murderer from the get-go.

Then, instead of this unjust situation being remedied on the arrival of the proper authorities, the case went to trial on the basis of incompetent evidence, the likes of Halsman’s Oedipus complex being cited. In yet another fiction-worthy turn of events, Sigmund Freud was on hand to proffer his expert opinion, luckily for Halsman, reminding the court that since the Oedipus complex is always present it is not suited to provide a decision on the question of guilt.

Indeed, Freud adds an anecdote that could well sum up the entire case: There was a burglary. A man who had a jimmy [crowbar] in his possession was found guilty of the crime. After the verdict had been given and he had been asked if he had anything to say, he begged to be sentenced for adultery at the same time – since he was carrying the tool for that on him as well. Amazingly, Freud isn’t the only one to speak up in defence of his fellow Jew – a list of Halsman’s supporters reads like a Who’s Who of the European intellectual heavyweights of the day, including Paul Painlevé and the French League for the Defence of Human Rights in Paris, Einstein in Berlin, Romain Rolland in Villeneuve, Thomas Mann in Munich and many others, the majority of whom were enlisted by the relentless work of Halsman’s sister Liouba, who wrote one thousand letters and travelled all Europe on Philipp’s behalf recruiting support for his case.

The Jump Artist is an audacious debut, not least because Ratner, after studying medicine at Johns Hopkins University, gave up his career as a doctor to write the novel. Initial critical responses in the US, where the novel was first published three years ago, suggest his gamble paid off – he was named by Publishers Weekly as one of the top 10 debuts of the year and won the inaugural Sami Rohr prize for Jewish Literature – though whether it will make quite such an impact elsewhere has yet to be seen.

The story itself is indeed fascinating but the execution is sometimes a little hazy by comparison. The internal monologue and switch between past and present, flashback and dream is somewhat confusing, especially at first, meaning it’s not an easy novel to sink one’s teeth into.

At the same time though, Ratner is a pleasingly subtle storyteller, refusing to push home too dictatorially the notion that the adult Halsman was entirely shaped by these terrible early years. Instead, he lets his readers make a more understated connection between the then future photographer and his experience of this tragedy.

This is perhaps most beautifully rendered in the symbolic image he imagines Halsman capturing of his father’s fall: “It was pictorial and still, like an image on a photographic plate – his father tilting backwards off the trail at an incredible angle, hands clutching the straps of his rucksack.” Given that Halsman advocated “jump” photography because he believed it stripped his subject of their reserve, revealing their soul, this image provides a hauntingly tragic counterpart to the photographer’s most famous works.

Lucy Scholes is a freelance journalist who lives in London.