At the end of Arabian Sands, British explorer Wilfred Thesiger writes about having lunch with his Bedouin companions, Salim bin Ghabaisha and Salim bin Kabina, at the Dubai home of an old friend, Edward Henderson. It was 1950 and, during the previous five years, Thesiger had explored Arabia's Empty Quarter, which takes in the UAE, Saudi Arabia, Oman and Yemen. Desert-hardened from his gruelling crossing (and historic recrossing) of this vast, southern expanse, Thesiger was introducing his two young followers to western dining with knives and forks. "While I was with you in the desert I fed and lived as you do; now that you are our guests you must behave as we do," he told Salim bin Kabina.

Arabian Sands, published six decades ago this year, remains a compelling read. Its clear and crisp narrative, recounting Thesiger's years in the desert, retains imagery that is as striking today as it was when it first hit bookshelves.

But when Thesiger left Arabia he worried about what the future held for his Bedouin companions. Both were by his side during his travels in and around the Empty Quarter, but as oil was already changing the lives of people living in the region, Thesiger feared that the life of the Bedouin was doomed.

Yet crucially, he achieved his heart's desire, or as the Explorers Club in New York referred to it in 1930, he explored "the broadest expanse of unexplored territory outside of Antarctica".

Except this hard-as-nails veteran of the Second World War was not the desert's first European explorer. Long before Thesiger made his mark on the Empty Quarter, and some 30 years before Arabian Sands was released, it had already played host to western exploration. While Thesiger wrote his name into the history books during his own desert trek, Europeans had disturbed the sands of this inhospitable land years earlier.

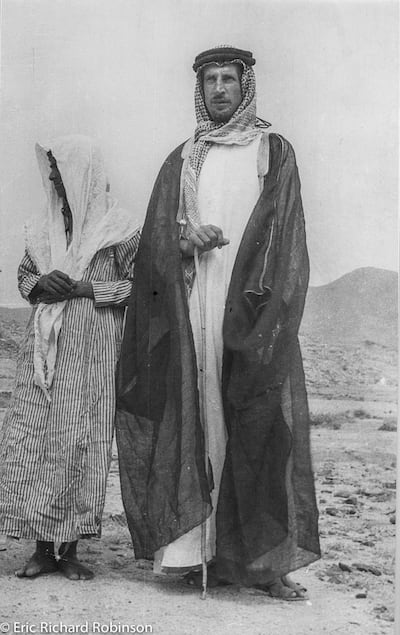

The earliest westerner to traverse the Empty Quarter was Bertram Thomas, a British political officer, soldier and traveller. On December 10, 1930, Thomas began his crossing of the Empty Quarter with his Bedouin guides at Dhofar and reached Doha 59 days later. It was an extraordinary feat of human endeavour and put the trailblazer on the front page of The New York Times. "I always have admiration for those people who actually walked into territory incognito, and Thomas was definitely that man," says Mark Evans, author of 2016 book Crossing the Empty Quarter: In the Footsteps of Bertram Thomas.

Thomas knew that he would never be given official permission for his pioneering trek and departed in secret. It was a bold move that would pay off as he overcame 1,300 kilometres of sun-scorched desert.

Evans, executive director of Outward Bound Oman, paid homage to Thomas by following his route across the Empty Quarter, prompting him to write his book. It was, he says, a chance to put his compatriot back on the map. "He has been totally overshadowed by the skills and the talents and the achievements of Thesiger, in terms of being a great photographer and being a great writer, and crossing the Empty Quarter twice, to the point that he has almost been trampled over and left in the dust. And yet he was the first," says Evans.

Thesiger's arguably more celebrated journey involved years of dedicated exploration. Thomas's two-month trek, however, was not spared the prospect of warring tribes and the unremittingly harsh environment that gave this 650,000-square-kilometre desert its fearsome reputation. "It took Thomas and Thesiger a while to adjust to the unpredictability of the regime and the routine of desert travel," explains Evans. "That, coupled with the fact they were both Christians and could have had their throats slit at any moment had they been discovered, adds a bit of spice to life and makes your heart beat a little bit faster."

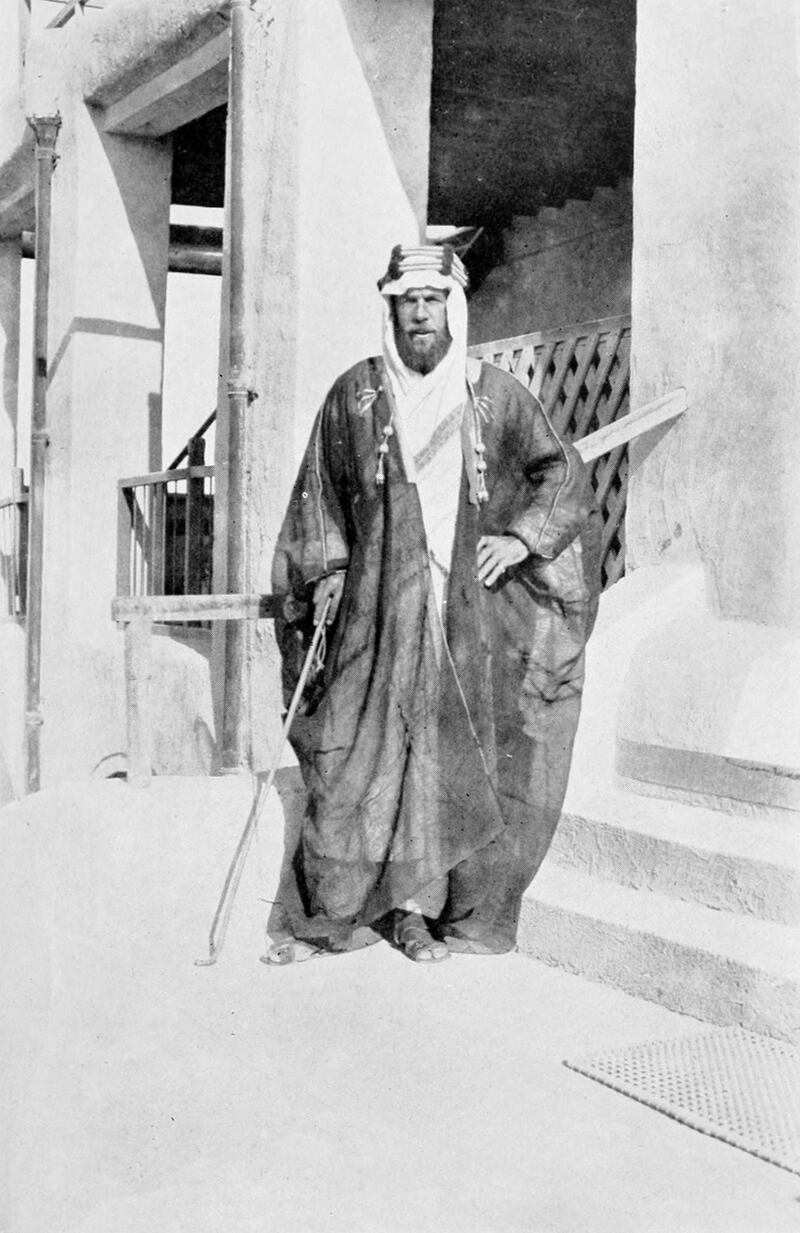

In matters of religion, the Empty Quarter's second European conqueror had no such concerns. His name was Harry St John Bridger Philby, and he converted to Islam by 1930. Yet despite his faith and role as an adviser to King Abdulaziz, Saudi Arabia's first ruler, from the 1920s, Philby was beaten to the punch by Thomas. But such was Philby's desire to become the first westerner to cross the Empty Quarter, which takes in most of the southern third of the Arabian Peninsula, that he shut himself away for an entire week after he learnt of Thomas's success.

In a fit of pique, the British national wrote to his wife, Dora, in England: "Damn and blast Thomas … I have sworn a great oath not to go home until I have crossed the RK [Empty Quarter] twice! And left nothing in it for future travellers."

Alexander Maitland, author of 2011 book Wilfred Thesiger: The Life of the Great Explorer, says Philby's status meant he was unable to compete with Thomas. "The very advantages that Philby possessed, most notably his working relationship with Abdulaziz, were the very things that caused him to be second," he says.

Looking for the backing and permission of the Saudi king, Philby – whose son was Kim Philby, the British double agent who defected to the Soviet Union during the Cold War – found himself at the mercy of Abdulaziz's good graces. When the Saudi ruler granted permission for the exploration in mid-December 1931, Philby was determined to forge his own path through the Empty Quarter, by exploring this ocean of sand dunes more extensively. Beginning in January 1932, his drive to make up for his past disappointment led him to investigate the area between Al Hofuf and Al Sulayyil in today's Saudi Arabia. All in all, he clocked up 2,700km of arduous travel. "As part of this journey, he covered more than 600km between wells," says Maitland. "With no water, except what they were carrying, it was a tremendous achievement."

When Thesiger took the baton in the aftermath of the Second World War, ostensibly researching the breeding grounds of locusts, he looked to explore the areas of the Empty Quarter where neither Thomas nor Philby ventured, such as the quicksands of Umm al Samim, which borders Oman. Philby, who died in Beirut in 1960, even intervened on Thesiger's behalf, by requesting a pardon from Abdulaziz, after Thesiger was detained for entering Saudi Arabia without permission. He was released after he spent a night in custody.

As Thesiger published a work documenting his travels across the Empty Quarter, so too did Thomas and Philby, with Arabia Felix: Across the Empty Quarter of Arabia and The Empty Quarter respectively. Evans and Maitland both contend that Thesiger's greater prominence today can be attributed to his more accessible writing style in Arabian Sands and the book's publication during the dawn of the mass media age.

Yet Jo Woolf, author of The Great Horizon: 50 Tales of Exploration, has particular admiration for Thomas, who died in 1950. Not only was he the first European to traverse the Empty Quarter, but Woolf praises the "self-effacing" manner with which Thomas completed his crossing. "He wasn't all about the glory of the achievements or accomplishments of exploration," Woolf says of this "quietly observant Englishman" who became Finance Minister and Wazir to the Sultan of Muscat and Oman. "He had this sense of integrity about him."

Thesiger was sensitive to changes in the region even before he left Arabia. In a 1948 letter to his mother, Kathleen, Thesiger wrote that Abu Dhabi was still "quite a small port on the [Arabian] Gulf and as yet quite unspoilt, but oil surveyors etc are busy in the area and I fear they will find oil and that all this will go".

Thesiger's prediction of modernity would prove correct. And after he made his final visit to the UAE in 2000, three years before his death in England, he realised that places such as Abu Dhabi had irrevocably changed, and that the petrodollar and new technologies had actually transformed the Gulf for good.

But how best to judge the defining legacies of Thomas, Philby and Thesiger? Maitland argues they should all be acclaimed for their individual achievements, not simply for how they compared as desert explorers. "Each of those men stands apart and alone as important figures in their own right," he says. "Comparisons are interesting and valuable, but it's also interesting and valuable to look at them as they were and in the context of their time."

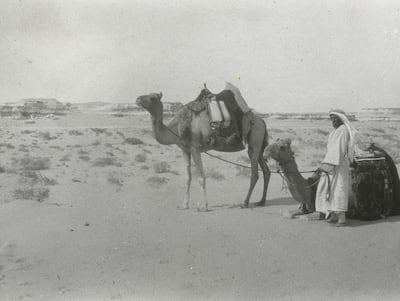

Today, camels have been replaced by air-conditioned four-wheel vehicles as tourists have flocked to the region to get a taste of desert life. But the Empty Quarter still holds some of the mystique that cast a spell over its first western conquerors generations ago.

Men could not have traversed the sands without the Bedouin

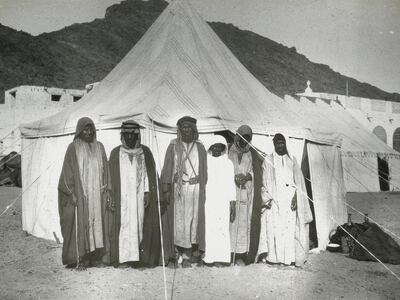

Bertram Thomas, Harry St John Philby and Wilfred Thesiger could not have traversed the sands without the help of the Bedouin.

But what of the Bedouin, or Bedu, who made the travels of those European explorers possible?

Long before these hardy men decided to have a crack at the Empty Quarter, the Bedouin had crossed and recrossed this vast and volatile sandbox.

For thousands of years, Arabia’s desert nomads, and their trusty camels, were the only people to explore the Empty Quarter.

As an outsider, Thesiger admired their astuteness and resilience. In a passage from his book, Arabian Sands, he says: “Bedu notice everything and forget nothing … their life is at all times desperately hard, and they are merciless critics of those who fall short in patience, good humour, generosity, loyalty or courage.”

Mark Evans, author of Crossing the Empty Quarter: In the Footsteps of Bertram Thomas, says the Bedouin were vital to the explorers. "The Bedu were critical to the travels of all British explorers in the sands of Arabia. Without them, the journeys would never have happened," he tells us. "They were the pre-expedition logisticians and the only ones who knew how to handle and care for the camels, on whom all lives, Bedu and travellers, depended.

“They were the only ones who knew how to hunt, a much-needed skill to break the monotony of bread, water and dates, and they were the only ones who knew the location of the waterholes.”