Wilkie Collins was one of the grand manipulators of 19th-century letters: a writer of whom it could be said, even in his teens, was possessed of the ability “to tell a lie beautifully”, and who would come to be regarded as the bequeather, the progenitor, of that great repository of dissimulation and revelation, the English detective novel.

Collins’ reputation as the father of this new form of fiction was secured in 1928, when TS Eliot described The Moonstone – Collins’ bewitching novel of 1868 – as “the first, the longest and the best of the modern English detective novel”. Although literary historians now argue that Eliot was mistaken in identifying Collins as the inaugurator of the detective novel, most are agreed that The Moonstone was the book in which its possibilities were given their fullest artistic recognition, and in which the genre itself first established its place in the English literary tradition. The Moonstone might not have been the first novel of its kind, but it was certainly among the best (journalist and literary critic G K Chesterton though it “probably the best detective tale in the world”).

While Eliot was writing about the importance of the world of Collins’ novels, others were turning their attention to the life of the novelist himself. Dorothy L Sayers – poet, essayist, translator, playwright and, like Collins, a writer of detective fiction – devoted 30 years to researching the life of her literary predecessor, yet was forced to abandon her projected biography because she had been unable to recover sufficient records to reconstruct Collins’ personal life. Collins, a private and secretive man, would have been delighted. Yet for us, the fact that Sayers’ biography never came to fruition is – or ought to be – a source of sadness.

Since Sayers abandoned her project, a number of accomplished Collins biographies have appeared, among them Catherine Peters’ The King of Inventors: A Life of Wilkie Collins, William M Clarke’s The Secret Life of Wilkie Collins, and Peter Ackroyd’s brisk and idiosyncratic Wilkie Collins. To these we can now add Andrew Lycett’s thorough and sympathetic Wilkie Collins: A Life of Sensation.

Lycett’s subtitle refers to three aspects of Collins’ life that he regards as connected: Collins’ appetite for what we might call the sensational life (booze, opiates, women and food), the “sensational” nature of his personal affairs, and his contribution to the nascent genre of the “sensational novel” (to which the detective novel was related). But before we arrive at the glamour promised by the subtitle, we first encounter Collins in his formative years.

William Wilkie Collins was born on January 8, 1824 at 11 New Cavendish Street, London. His early education was supervised by his mother, Harriet, to whom Collins later attributed “whatever of poetry and imagination there may be in my composition”. His father, William, was an artist. He was also a High Tory who once confessed to a friend “that he equated political reform with cholera as a scourge of the age and as evidence of God’s wrath”, and an oppressively pious member of the High Church. His correspondence was heavy with unctuous sententiae (“Your heart is not insensible to the mercies of Providence,” as he once gallantly wrote to his mistress), and an evening’s diversion came in the form of readings from the Bible.

By the age of 11, Collins was being educated at the Maida Vale Academy, a reasonably happy experience that was made more agreeable still when his father decided to take the family on a trip to Italy. The trip fired Collins’ lifelong love of the Mediterranean, and furnished him with an anecdote that would, too, last him a lifetime: that it was in Rome, at about the age of 13, that he had experienced what his great friend Charles Dickens described as “his first love adventure”, which “proceeded, if I may be allowed the expression, to the utmost extremities”.

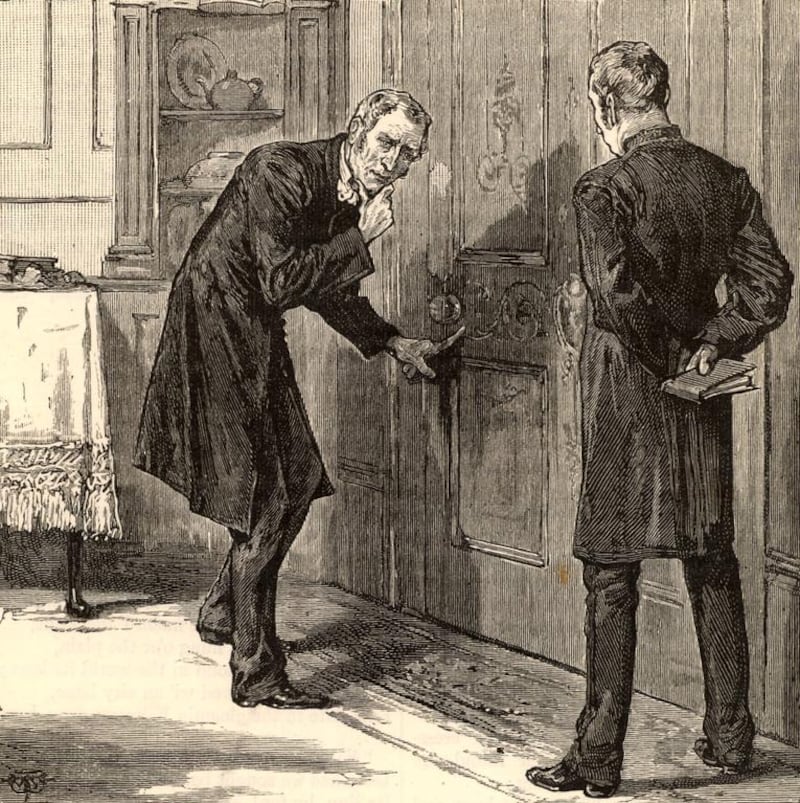

Collins resumed his English education at an academy run by the Reverend Henry Cole, a Biblical fundamentalist of extreme opinions whose curriculum, it was hoped, would curb Collins of inclinations that were becoming alarmingly sybaritic. It did not. But it was here that Collins began to nurture his love of storytelling, initially at the behest of one of the older pupils, who liked to indulge his literary sensibilities of an evening by declaring: “You will go to sleep, Collins, when you have told me a story”. “I learnt to be amusing on a short notice”, recalled Collins, “and have derived benefit from those early lessons at a later period of my life.”

After Cole’s, Collins managed to avoid going to Oxford; was apprenticed to a firm of London tea merchants; and eventually – another concession to his father – found himself reading for the bar. Collins did qualify, but through all these years – years in which his father was hoping he would find himself a proper job – his true commitment was to his writing. By the summer of 1843, he had published a successful story – Volpurno – in the New York magazine, Albion, also known as the British, Colonial and Foreign Weekly Gazette. Not long after, he was hooked. Not long after, he would soon do away with his Christian name altogether and refer to himself exclusively as Wilkie.

It was around this time that Collins’ father died. His passing came as a blow, yet it also seems to have offered Collins a sense of release. He was now dedicating himself exclusively (save for a brief flirtation with painting) to matters literary and dramatic. He wrote plays, travelogue, stories and articles. He embarked on a biography of his father. He was working on a novel. And, crucially, he met Dickens, for many years his greatest celebrant and his greatest friend.

It was from this moment, at the age of 27, that Collins saw his life become sensational: a whirlwind of writing, acting, travelling, carousing, secrecy, ill-health and pain. While writing the novels – The Woman in White and The Moonstone – that would make him justly famous, and on which his reputation now rests, he suffered terribly with anxiety (“The hardest disease to cure that I know of is – worry”); lost a friend to suicide, his brother to cancer, his mother to old age (“the bitterest affliction of my life”); struggled with something close to alcoholism; endured periods of artistic depression in which he felt miserable when he was writing and miserable when he wasn’t; and was routinely afflicted by rheumatoid gout, for the alleviation of which he was prescribed laudanum – to which he became addicted.

So severely addicted, in fact, that while away on one of his many travels, a friend had to visit four chemists in order to procure sufficient quantities of the drug to satisfy Collins’ needs. It was not long after this episode that he was trying to break his addiction to laudanum by injecting morphine directly under the skin, and towards the end of his life he was so dependent on the drug that he was unable to leave the house without carrying with him a hip flask of the stuff. “Life would have been almost unbearable to him without it,” concluded a friend.

In addition to all of this, Collins was devoting a ridiculous amount of energy to his romantic life, largely to ensure that he was able to maintain two relationships at once. First into his orbit was Caroline Graves, who was born out of wedlock and with whom he was seldom seen in public (Dickens felt her irritating; Collins called her his “housekeeper”). To Caroline’s ministrations he would add those of Martha Rudd, a 19-year-old illiterate whom he met in a pub and who carried the appearance, in Lycett’s lyrical formulation, of a “buxom wench”. Collins kept both these relationships going simultaneously, housing each mistress within handy distance of one another in his favourite neighbourhood of Marylebone.

Lycett covers all of this with diligence, energy and elegance, yet one finishes the book with the feeling that he admires Collins more as a man than as a writer. Fair enough, in a way. This is not a critical biography, nor does it claim to be. And there was much in Collins to admire. As Lycett says, he “was certainly not a typical self-righteous Victorian male. If there was a model, he was the exception who proved the rule”. He was avowedly philo-Semitic; he disliked oppressive organised religion; he was hostile to marriage on the grounds that it did both men and women a disservice; he was a reasonable father and a fine friend.

Yet Collins could also be thoughtless, hypocritical, brutal, shortsighted, and occasionally repugnant. He would make rather a show of sympathising with the plight of prostitutes, but this sympathy was not so deeply felt as to prevent him from using them himself, or from joking with Dickens about the diseases he had contracted in the process. Caroline Graves was for years hidden from his friends and family, while his attraction to Martha was not much more than snobbery made flesh (she was his social “inferior”, which rather got him going). Throughout his life, he had difficulty escaping the idea that women were either angels or whores, and he was capable of behaving ruthlessly. Lycett does not quite evade these aspects of Collins’ character, but he doesn’t make them as central as they ought to be. One consequence of this is that the praise of his subject can sometimes feel rather weightless – a charge that could never be made about Collins when he was writing at his best.

It was in that writing – in that twilight world where doors met listeners – that the tensions and contradictions of his personality were most acutely apprehended, most unblinkingly examined, most memorably revealed. Collins thought it was the duty of the writer to tell a good story. At that he was supreme, but he could also do more. He had the ability to weave fictions that were beguiling, thrilling, transformative, penetrating and edifying. It was an ability that was granted to only a handful of Victorians. It was an ability, one might say, to tell a lie beautifully.

Matthew Adams is a London-based reviewer who writes for the TLS, the Spectator and the Literary Review.