In field after field, we have seen it: new hits piggyback on old hits. The multiplex is an endless swirl of Marvel Cinematic Universe entries and Star Wars sequels. One of the biggest publishing successes of the past decade was constructed out of repurposed Twilight fan fiction. Brooding TV heroes bred their own offspring, propagating until they threatened to submerge what was once the Golden Age of Television. So it should come as no surprise that the same should be true of the subset of non-fiction books we might call inspirational social science.

Where once had reigned Malcolm Gladwell and the now-discredited Jonah Lehrer, peddling a craftily-varied array of researchers' findings, historical anecdotes and brief biographical profiles, all orbiting a simple-to-follow central hypothesis, there now comes Derek Thompson, a senior editor at The Atlantic. Thompson's book asks a compelling question: what goes into making something a hit? Drawing on everything from the belated success of Bill Haley & His Comets' Rock Around the Clock to the career of designer Raymond Loewy, to the storytelling prowess of George Lucas, Hit Makers casts its net widely to assay the principles of giving the audience what it may not yet realise it wants.

“The power of well-disguised familiarity,” Thompson argues, “goes far beyond film. It’s a political essay that expresses, with new and thrilling clarity, an idea that readers thought but never verbalised. It’s a television show that introduces an alien world, yet with characters so recognisable that viewers feel as if they’re wearing their skin. It’s a piece of art that dazzles with a new form and yet offers a jolt of meaning.”

Thompson is offering Hit Makers as a work of well-disguised familiarity, going so far as to draw on material from other historical/social-science popularisers like Steven Johnson, whose The Ghost Map is briskly summarised in one aside about the London cholera outbreak of 1854. Thompson himself is a writer in the mode of Loewy, whose self-declared motto, Maya, argued that "people gravitate to products that are bold, yet instantly comprehensible – 'Most Advanced Yet Acceptable.'"

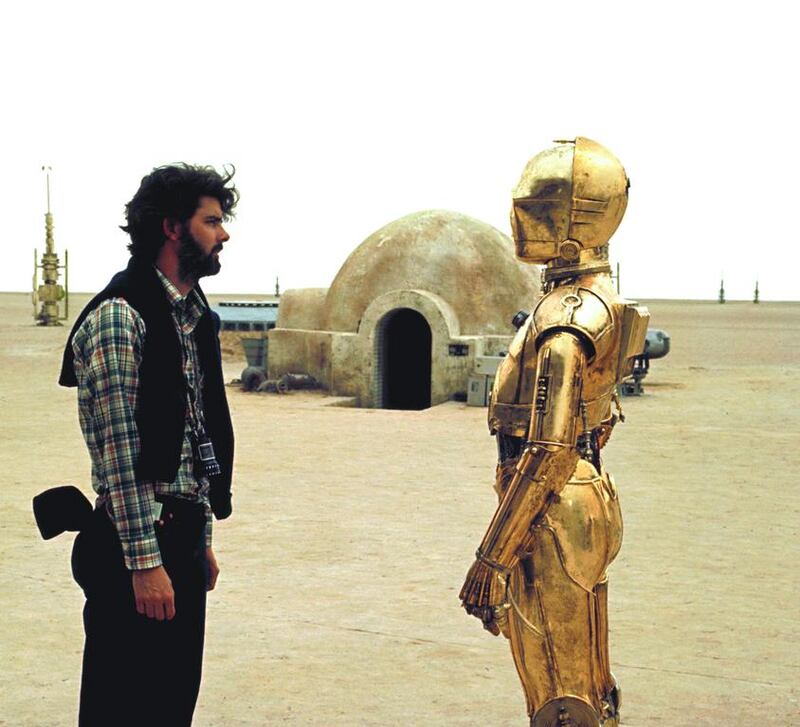

Hit Makers is an expert refashioning of well-known material, gravitating to deeply familiar topics in order to fill in the edges and illuminate the hidden nooks. (I, for one, hadn't known that Tetris was created by a Soviet computer scientist.) On Lucas, he says the director would nervously trim his hair with scissors as he wrote his scripts and that he himself borrowed from a tradition of cinematic tales of heroic derring-do, featuring figures like the Shadow and the Lone Ranger. Thompson picks through the inspirations for Star Wars, ranging from Flash Gordon to Akira Kurosawa's The Hidden Fortress, describing Lucas's film as "an original compilation". "It's not like one kind of ice cream," Lucas said of his work, "but rather a very big sundae."

The book, then, looks at everything from the history of Impressionist art to the musical component of political speechwriting, to the business model of ESPN. Thompson circles a fundamental conundrum of popularity. Are audiences in search of something new, or something familiar? Do they want safety, or are they seeking a thrill? There is a good deal of evidence summoned for both sides of the debate.

Hit Makers briefly tells the story of Charles Douglass, whose "Laff Box" was the first television laugh track, not-so-subtly informing viewers when and how to laugh at their favourite sitcoms. Spotify data indicates that most users stop seeking out new music at the age of 33.

There is also the arrival of the genuinely new, which Thompson indicates is often the result of an artful tweak of the staid consensus. Success, he argues, is less about the inherent value of the new than the confluence of the right work at the right moment in the right place. It is Whitney Wolfe, a young Tinder employee visiting sororities at Southern Methodist University, convincing all the sisters to sign up for her dating app, and then taking it to the neighbouring fraternities to show members all the attractive young women already logging onto the site.

It is 9-year-old rhythm-and-blues fan Peter Ford, whose father Glenn was about to star in a juvenile-delinquency drama called Blackboard Jungle. The film's director, Richard Brooks, was in search of a fresh song to play over the credits, and on a visit to Ford's house, listened to some of his pre-teen son's new records before selecting one called Rock Around the Clock which had flopped upon release the previous year.

It is, as Thompson wisely points out, the incredible, underplayed influence of the Impressionist painter Gustave Caillebotte on the reputations of his contemporaries. By donating his extensive collection of works by his contemporaries, including Auguste Renoir and Claude Monet, to the French government, he helped to create the Impressionist canon. We love the Impressionist art that we do, argues Thompson, not because it is inherently better than more obscure work but because it is more familiar.

In a similar vein, Thompson notes the influence of charts and ranking systems on our consumption. We download only the most popular apps for our smartphones and prefer the songs that others already prefer: “The mere existence of rankings – the simple signal of popularity – made the biggest hits even bigger.”

In perhaps his most compelling line of argument, Thompson pushes back against the entire concept of virality, seeing little beyond the usual measures of success in slightly-updated form. Thompson looks at the Fifty Shades trilogy and the "Kony 2012" online video (which called for action against Ugandan militia leader Joseph Kony) and sees examples of 21st-century broadcasters amplifying a weak signal and spreading it to the masses.

So "Kony 2012" did not spread from anonymous user to anonymous user, unseen by the custodians of culture, but rather through the social-media feeds of superstars like Oprah Winfrey, Rihanna and Taylor Swift. And Fifty Shades, while finding an early audience through a fan-fiction website, came to mass public attention via the behind-the-scenes efforts of prominent publishing executives who elevated author E L James's obscure e-book into a blockbuster book and film series.

And yet, the portrait Hit Makers paints is one where "the world's attention is shifting from content that is infrequent, big and broadcast ... to content that is frequent, small and social". Thompson finds hope in the internet's ability to "empower individuals, untethered from the old gatekeepers that once controlled distribution, marketing and hit-making".

There are the requisite stories of the law-school dropouts turned Vine superstars, but the evidence of a brave new world for lone creators feels thin. Lucas doesn't make Star Wars any more – Disney does. And even in the major leagues, the taste for the familiar has often overwhelmed the original – or, to be more precise, originality must confine itself to familiar borders.

Thompson notes that for 15 of the last 16 years, the top-grossing film in the US has been either a sequel or an adaptation.

Hit Makers is a smooth read. As Thompson demonstrates, repetition is itself the foundation of music; without it, even the most astute listeners have difficulty understanding a series of interconnected sounds as musical. Repetition is the heart of the pop social-science tome as well – repetition of familiar stories, and repetition of a well-honed model of storytelling.

To critique Hit Makers for its nagging familiarity is to peruse the shelf of books with gavels and handcuffs on their covers and bash them for their predictable array of dead bodies and grizzled investigators. This is, at heart, what they do.

Hit Makers' own well-disguised familiarity will probably not stop any of its intended audience from picking it up at their local bookstore or airport kiosk – nor should it. But it may very well prevent it from being quite as memorable as its author hopes.

Saul Austerlitz is a frequent contributor to The Review.