One of France’s most popular post-war writers also happened to be one of its most prolific. Frédéric Dard wrote at least 284 thrillers (no one has been able to come up with an exact figure), selling in excess of 200 million copies in France alone. He wrote under 17 different pen names, one of which produced his most famous creation, San-Antonio, a kind of French James Bond, whose adventures captivated French readers from 1949 to 2001.

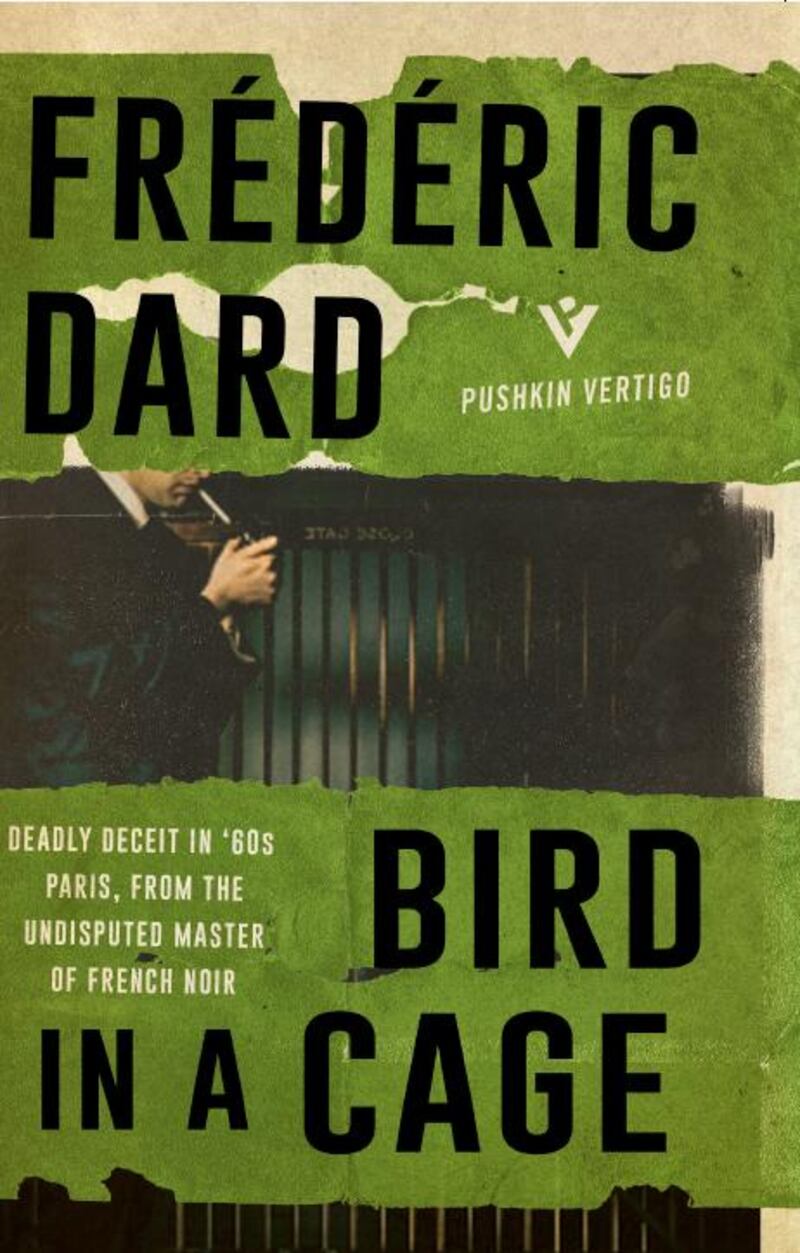

Despite Dard’s continental success, his work has remained unavailable in English. Pushkin Vertigo has decided to redress that by publishing a handful of his titles this year.

The first to appear is Bird in a Cage, a novel originally published in France in 1961 and now neatly translated by David Bellos. It is no Gallic 007 escapade, rather one of Dard's brilliantly named "novels of the night", a strain of books comparable to his equally prolific friend Georges Simenon's non-Maigret range of romans durs ("tough" novels).

Both sets of books are dark psychological thrillers characterised by flinty prose, murky intrigue, offhand violence and moral quandaries. Dard packs all of this into Bird in a Cage's 117-pages and leaves us hungry for the next novel.

He begins with his narrator, Albert, returning to his dead mother’s Paris apartment after a six-year absence. It is Christmas Eve, and to combat his pain (“it felt like the slipknot on a rope around my chest was being tightened without pity”) and his loneliness he heads out into the festive city.

After impulsively buying a small, cheap trinket – a tiny bird in a cage – he dines in a brasserie where, at the next table, he sees a young girl and her mother, the latter reminding him of his ex-lover Anna.

Amazed at the similarity and entranced by a kindred spirit, a sad soul mate, Albert walks the woman home, has a drink and hangs his birdcage on her Christmas tree.

Once Madame Dravet has put her child to bed she asks Albert to accompany her on a night-time stroll through the icy streets, during which she opens up about her unhappy marriage. But when they return to her place they notice her errant husband’s coat now hanging on a peg, his corpse lying on the sofa, and Albert’s birdcage decoration missing from the tree.

From here, Dard allows his plot to thicken. Before Mme Dravet calls the police, Albert warns her that he is a bad alibi: his six years away were in fact six years inside jail for the murder of Anna.

With romance no longer in the offing, Albert slopes off, but when he is drawn back a little while later he discovers the dead body gone and, bizarrely, his birdcage dangling again on the tree.

In such tight confines, Dard ratchets up the tension (is the murderer close to home and hiding out in the building?), stokes suspicion (what are the two red flecks on Mme Dravet’s cuff?) and plays an ingenious smoke-and-mirrors guessing game, a combination of whodunit and howdunit.

“I sincerely believe you have pulled off the perfect crime,” Albert tells the killer at the end, and we can’t help but agree.

Throughout the proceedings, Dard creates an atmosphere that both seduces (Albert re-exploring his old quartier in the “greasy rain”, inhaling the stench of wet soot and cooking oil) and stuns: “The ensuing silence was as sharp as a prick on a taut nerve.”

Dard’s literary career may well have been a case of quantity over quality. However, this short, sly novel of the night has more than enough substance and mystery to keep readers awake and engrossed.

Malcolm Forbes is a freelance reviewer based in Edinburgh.