Johannes Urzidil's The Last Bell carries the subtitle "Bohemian Stories", making it, like Giovanni Verga's Little Novels of Sicily, Isaac Babel's Tales of Odessa and Leo Tolstoy's Sebastopol Sketches, a collection of short fiction about people and place – or, more specifically, region and residents. Containing five finely crafted stories set in Prague, the countryside and little towns where time stands still, Urzidil presents Bohemian realms fraught with chaos and foreboding, and striking, tragicomic characters.

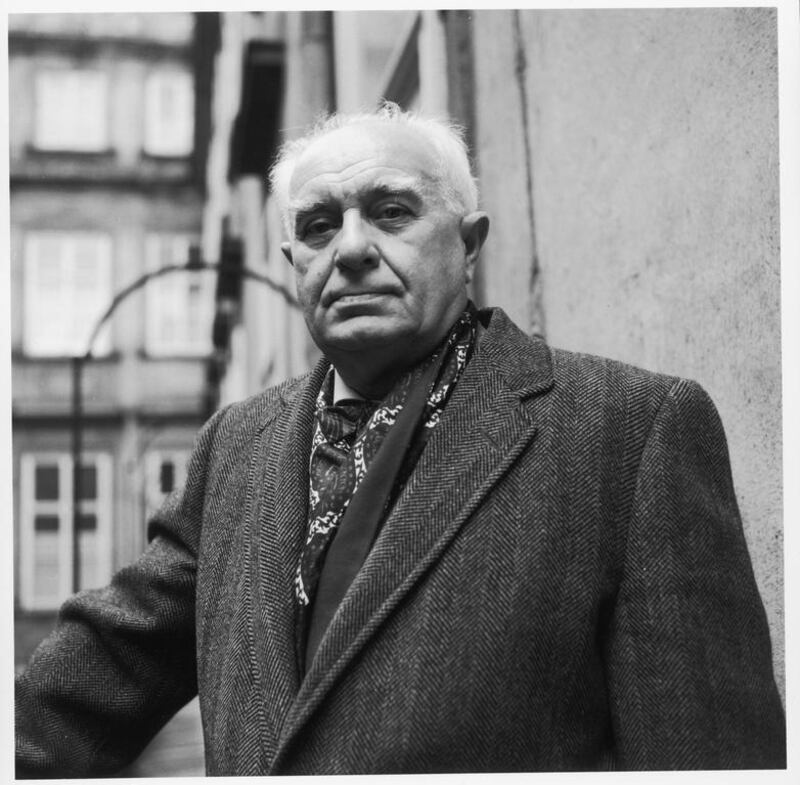

In the Anglophone world, Urzidil (1896-1970) remains an unknown quantity. Born in Prague to a German father and a Jewish mother, he mixed with members of the “Prager Kreis” (Prague Circle) including Franz Kafka, Franz Werfel and Max Brod, worked at the German embassy, and produced poetry, fiction and essays. When Hitler invaded and the Gestapo closed in he fled his homeland. While in exile in America he produced some of his most successful work, much of it with a Bohemian backdrop.

The stories in The Last Bell – published for the first time in English and neatly translated by David Burnett – provide a taste of Urzidil's talents. The strangest, slipperiest story, The Duchess of Albanera, is dedicated to Brod, and feels like an attempt to walk in Kafka's shoes. Wenzel Schaschek, a Prague bank clerk, committed bachelor and creature of habit, takes a break from talking to the usual inanimate objects that fill his regimented days and humdrum existence – furniture, flowers, food – and enters into an intense two-way conversation about women, beauty and murder with the love of his life – a painting he stole from the State Gallery three days previously.

Less far out yet further afield, Siegelmann's Journeys takes us away from the city and into a rural town, where a travel agent who has never travelled attempts to woo a fellow lonely soul by rehashing and reliving his customers' exotic adventures and experiences. "I don't lie," he assures himself, prior to wrecking his relationship. "I merely choose a convincing form for reality and truth."

Siegelmann's storytelling consists of tempering "the fantastic with the ordinary". His creator employs a similar technique in Borderland, a sombrely beautiful tale about a special, "magnetic" 12-year-old girl. The story deftly explores two meeting points – the juncture between the everyday and the outlandish and the forested frontier dividing Bohemia and Austria.

Urzidil bows out with Where the Valley Ends, another woodland story, and another that revolves around the consequences of a theft – on this occasion not a painting but a cheesecake.

But it is the titular tale that starts the proceedings that steals the show. The Last Bell has a captivating protagonist in feisty, unflappable maidservant Marška. When her employers ("the Mister" and his Jewish "Missus") are forced to up and leave with only two small suitcases, she is left with their Prague apartment, their money and belongings. She invites her younger sister to stay, ignores all the clocks ("We don't need hours or time") and settles into her new role as "woman of private means".

When the girls attract the attention of two Nazi officers, their lives sharply change. Despite their admirers’ flattery, Marška remains sceptical: “Maybe they haven’t murdered anyone yet, but it’s better to call them murderers right from the start so you don’t have to correct yourself later.” And indeed she doesn’t. Urzidil modulates his tone and sublimates his heroine’s antics as he leads to a denouement in which Marška witnesses the full might and cruelty of the city’s “uniformed invaders”. Unlike Schaschek – who after stealing his painting unwittingly unleashes calamity and warps two identities – making one man “guilty-innocent”, the other “innocent-guilty” – Marška finds herself faced with the choice, or the challenge, of taking control and averting disaster by saving a Jewish life.

This remarkable, multifaceted story showcases various Czech styles. A pub brawl and other rambunctious high-jinks are redolent of the escapades of Jaroslav Hašek’s good soldier Švejk; the more absurd violence (the sisters’ father is crushed by a manure cart), darker humour and skewed wisdom is as potent as that magicked up by Bohumil Hrabal; while the pockets of real horror, particularly the round-ups of Marška’s Jewish neighbours, have the same emotional clout as those that punctuate Jirí Weil’s Nazi-occupied novels.

Ultimately, though, this miniature masterpiece and the other four stories come to us in one voice, that of an inexplicably overlooked Czech master who is only now finding an English-speaking audience. Credit is due to Pushkin Press for rediscovering Urzidil. With luck, there will be more stories to tell.

Malcolm Forbes is a freelance reviewer based in Edinburgh.