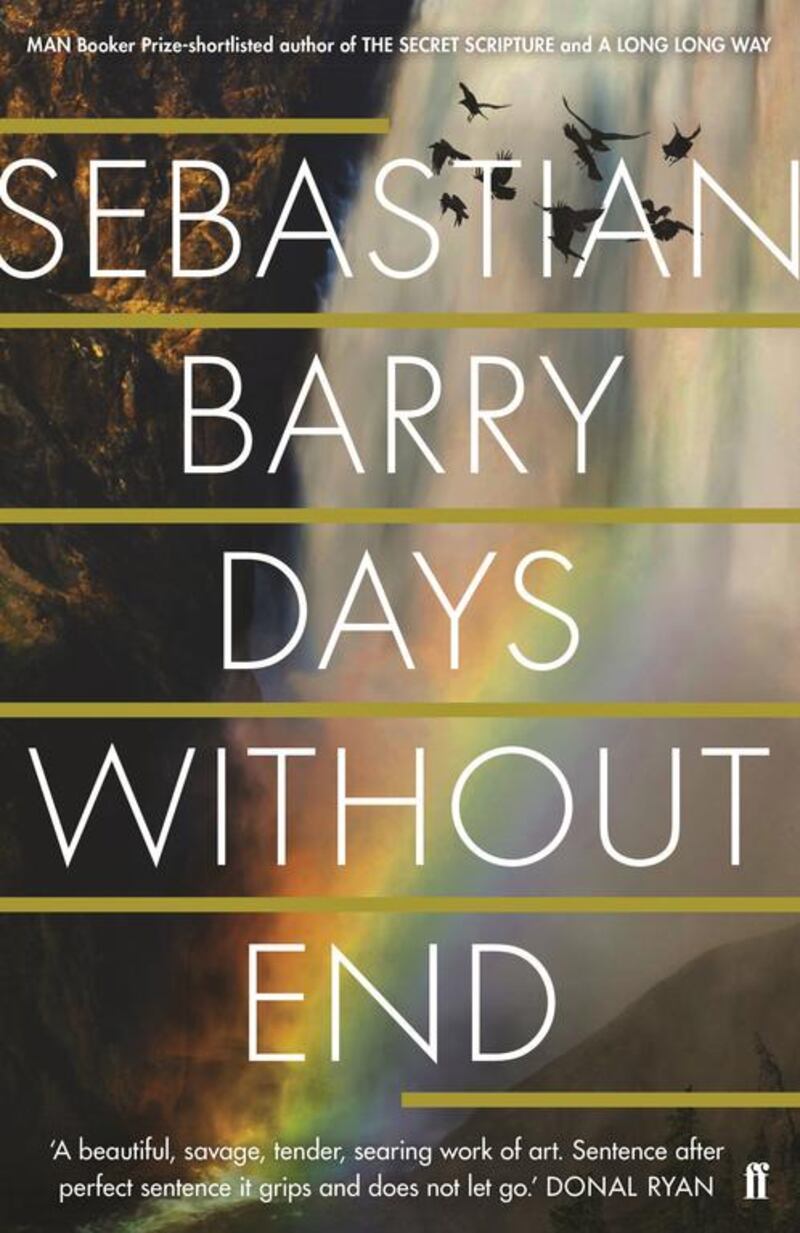

Days Without End

Sebastian Barry

Viking

Dh82, from Amazon

Sebastian Barry has an uncanny knack for capturing a certain kind of Irishness. Many of his novels are loosely linked to an Irish family, the McNultys, with vulnerable characters battling displacement, tragedy and circumstance.

But there is a certain endurance to them, too – an inherent willingness to see good in the world. In his latest, Days Without End, the connection to the McNultys is Thomas, an ancestor who is orphaned during Ireland's Great Famine. He stows away on a boat to North America and becomes a soldier, complicit in the blood and horror of the battles with the Sioux in the Indian wars of the mid-19th century.

Written in the kind of old, drawling American dialect so redolent of that period – “It was in the time of noisy weather that the first trouble came… we rode forth to meet it” – Barry constructs fantastically widescreen depictions of life on the Oregon Trail, tapping directly into the folklore of the establishment of the United States.

However, he never forgets the brutal way in which Native Americans were forced into submission. His account of a massacre at a smoke-filled encampment, in which they “saw the shapes of Indians and stabbed them with our bayonets… I stabbed and stabbed”, has a horrific coda in which he realises they have indiscriminately attacked the hiding place of women and children. There’s not one warrior among the dead.

These set pieces, combined with great storms, chilling cold and almost medieval living conditions are the stuff of epic cinema, and some of the descriptions go from earthily real to achingly poetic in a sentence, which is essentially Barry’s great skill.

But he also finds a micro story in this macro landscape. Thomas and John Cole’s relationship begins oddly – as boy dancers dressed up as women to entertain the miners – but they become incredibly close as they fight in the Indian wars and then the civil war. In such confusing days where anything seems possible, or indeed up for grabs in this adventure of an emerging nation, they end up forming a family of their own with another young orphan, a Sioux called Winona.

It is here that Barry’s great project comes to the fore again. Throughout the hardship and tragedy, there is still stoicism and hope. Thomas can’t believe that a tomahawk hasn’t split his skull, and he can’t feel anything other than dislocation in this kill-or-be-killed environment, yet somehow he does not allow the horror to pollute his soul.

For some, that might be too neat, too literary a reading of an unbearably intolerant time. However, Barry finds a new way of telling a well-worn story, and finding the essence of humanity.

Ben East