When Richard Ford's novel Canada was published in 2012, many critics made mention of its arresting opening line: "First, I'll tell about the robbery our parents committed. Then about the murders, which happened later." The Lebanese author and journalist Rabee Jaber trumps Ford by kick-starting his novel Confessions with a terser, more immediate, arguably more repellent yet ultimately more inviting first sentence: "My father used to kidnap people and kill them."

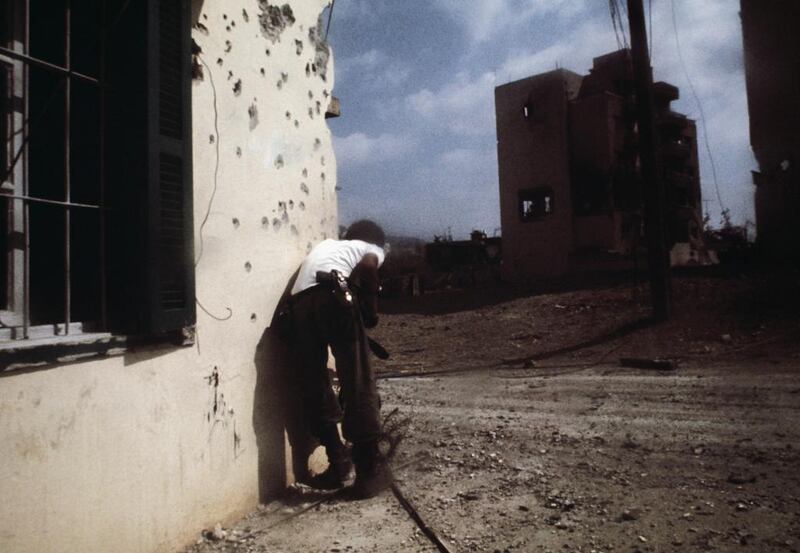

Death stalks the pages of Jaber’s novel. It plays out against the violence of Lebanon’s Civil War, and by the end of the book all of its characters have been affected by the conflict – some merely tainted, others corrupted or destroyed.

Its narrator is Maroun, who looks back on the first decades of his life growing up in East Beirut. We follow him through the years, from the mid-70s to the present day, over which time he tries to make sense of the chaos and suffering on the streets and at home, while also attempting to understand who he is and where he came from.

Maroun begins by ransacking his mind for his earliest memories. He remembers his mother making date cookies, his sister peeling onions and his father carrying him across a river.

But in with the fond reminiscences are moments of profound gloom.

He recalls the picture of his murdered brother hanging on the family’s living room wall, and how his sisters would look at it, then at him, and burst into tears. His mother would cry in church. Later, he remembers not glances and gestures but his older brother’s words: their father changed “in a single night and day”.

News comes in of his atrocities: “He was forcing people out of their cars and beating them. He was shooting them and throwing them off a bridge.”

But after spending several pages dredging up and sifting through childhood images, Maroun breaks off and decides to start afresh. “In order to tell you my story, I need to start with my little brother. They kidnapped and killed him.”

A graphic and terrifying sequence of events unfolds. After an agonising absence, the tiny bloody corpse of a 9-year-old boy shows up; a father buries his son then begins a retaliatory killing spree; in one attack he and his gang open fire on a family in their car, sparing only one occupant, a young boy, whom the father takes home and names Maroun after his dead son.

“I’m Maroun,” our narrator then announces. “I’m the boy they kidnapped.”

Jaber’s fiendish twist transforms the novel. From this point on we read it as not only an account of a life lived but also a study of selfhood, identity and the illusoriness of memory.

Maroun, the surrogate son, raids his past to fill in the gaps and to get peace of mind. He recreates his school years, describing the shelling he and his classmates endured during lessons or the sniper-fire they were exposed to in the playground.

He collects shrapnel off the streets and makes illicit trips to the demarcation line or bombed buildings. In addition he relays deaths, his brother’s war exploits and his sister’s departure from “this unlucky country”; he dates a girl, forges a strong friendship and studies at the American University.

It is when he tries to find out about his real family – and his real name and date of birth – that he hits a dead-end, discovering that all the records from the war were burned, lost, stolen or destroyed.

Confessions could just as accurately be called "Memories". "I'm gathering up my memories and watching them flow," Maroun tells us.

“I’m extracting the memories from the back rooms, I’m taking untrodden paths to find myself.”

Some of those memories are triggered by Proustian prompts – bitter oranges, fava beans, pumpkin jam – others by confronting his demons.

Maroun repeats himself, gets sidetracked, stumbles during traumatic recollections and fixates on small, bizarre details, but each jerky, meandering, rough-edged sentence is both mesmerising and convincing.

Jaber has written 18 novels – including The Druze of Belgrade which won the International Prize for Arabic Literature – but Confessions is only the second to be translated into English (beautifully so by Kareem James Abu-Zeid).

With luck, more of his back catalogue will become available to English readers. Until then, we have this clever and illuminating novel.

Malcolm Forbes is a regular contributor to The Review.