In a breezy tour across more than 3,000 years of history, best-selling historian Mark Kurlansky takes a humble, everyday object and tells a big story about human civilization. A popularising pioneer of a genre known as microhistory, Kurlansky has conjured worlds out of salt and cod. In his new book, Paper: Paging Through History, he does the same for paper.

Though it is not certain beyond a shadow of doubt, the Chinese appear to be the first to have started making paper. The oldest piece of paper discovered dates back to 252 BCE. Fabric scraps were beaten down into a pulp with a mortar, then moulded into shape. Subsequent advances allowed paper to become thinner, more common and cheaper to make. It was a revolutionary development.

Papermaking spread to other parts of the globe, notably to Central Asia and the Islamic world. One account credits Chinese prisoners, captured at the 751 Battle of Talas by an Arab general, for spreading the practice to Central Asia.

But paper was in the region well before the date. (In 1907, an archaeologist unearthed a packet of letters written by an aggrieved wife, dating from 313-314, who lamented “that I would rather be dog’s wife or pig’s wife than yours”). Samarkand, at the western edge of the Silk Road, became a major centre of papermaking.

One scholar has called the Islamic Empire the world’s first truly literate society. “The Muslims believed that the written word was a privilege not just for the elite few, but for the population at large – rich and poor, religious and secular,” Kurlansky writes.

And paper led the way. Under the Abbasid dynasty, Arabs would create one of the great paper-centric civilizations. “A golden age of culture and learning”, it was also an age of paper. Parchment and papyrus gave way to paper made in mills powered by water.

Baghdad, situated on a river, was a natural site for such operations and became known for its quality paper, which was deemed fine enough for the Quran. Damascus also became a centre of papermaking and was famed for its “charta damascena”, whose fame spread to Europe. Hemp, linen, rags, ropes: all proved suitable for papermaking in the Arab world.

Kurlansky covers an enormous amount of ground as he hopscotches through the ages, leaving one civilization behind as he leaps to another.

If Baghdad's libraries swelled, those in Europe by contrast were laggards. Paper was late in coming to Europe. But the Muslim conquest of Spain, and the rise of Andalusia, spread papermaking to the continent. Fabriano, in Italy, emerged in the 13th century as a centre. (The Fabriano word for rag paper derives from the Arab quothon. The Fabrianese were also the first to bundle the paper into risma – reams – also from the Arabic.)

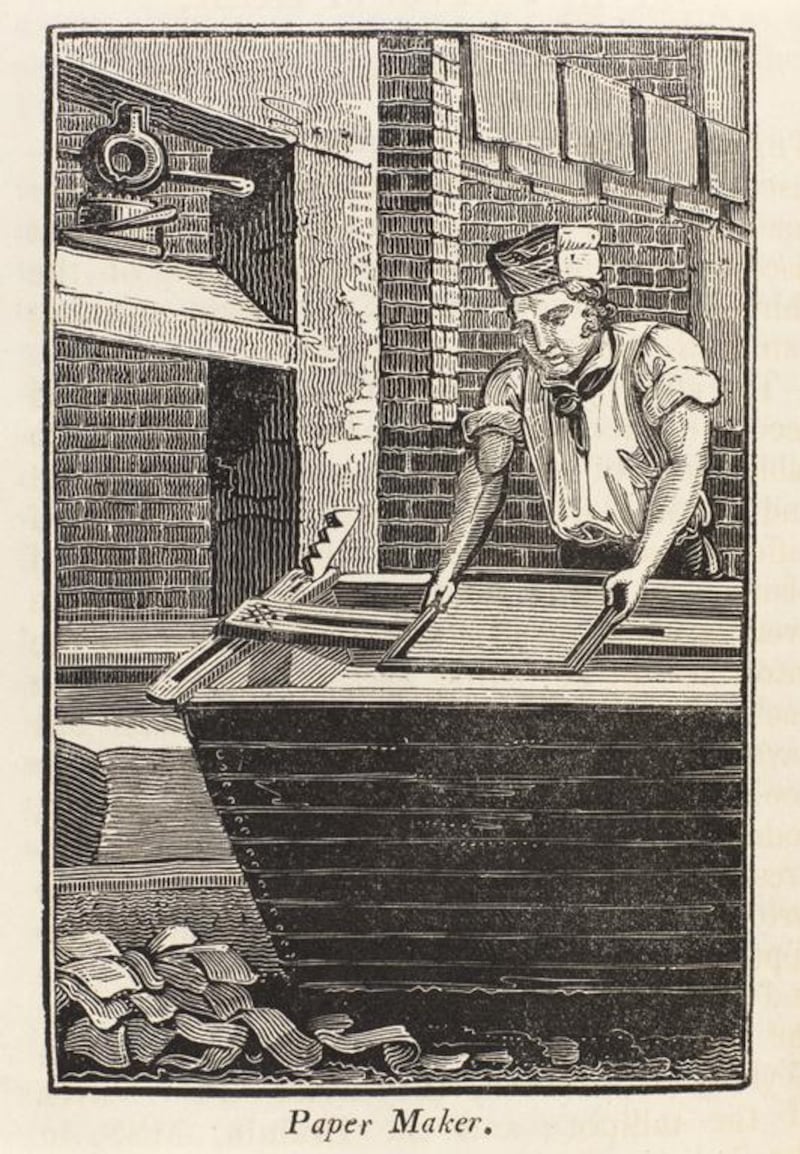

The Fabrianese were pioneers, switching the grain-based finish – known as a sizing, it kept ink from spreading and blurring – used by Arabs, for a gelatin made from sheepskin, which was more suited to Europe’s humid climate. They also developed the water-powered drop hammer, which vastly increased pulping capacity, among other innovations.

“With its use of drop hammers, animal sizing, wire moulds, and watermarks, Fabriano had reinvented paper – and defined papermaking for centuries to come.”

Papermaking moved into Germany and beyond. Though paper itself is a technology, Kurlansky warns against the “technological fallacy”. Technology does not change society, he argues: rather, “society develops technology to address the changes that are taking place within it”.

The advent of the printing press itself is a case in point: the pressing demands of 15th-century Europe, and the ferment of ideas, demanded a technology that allowed for the faster reproduction of books and documents. Moveable type, an Asian innovation, helped make this possible. Books poured forth from the presses.

Thinkers committed their ideas to paper. But so did visual artists. Kurlansky provides a detailed account of the ways Leonardo da Vinci and Albrecht Dürer used paper in their art. (Da Vinci left behind some 4,000 works on paper).

Kurlansky’s sections on Asia and the Islamic world are among his most interesting; but as he details the rise of Europe, his account takes on a more familiar feel. Rags gave way to wood pulp in the 19th century, though paper derived from wood is quick to decay.

Still, the sweep of Kurlansky’s story shows that paper is a remarkably durable invention, endlessly adaptable.

Paper still has life, even in the digital age. Sure, we send emails instead of old-fashioned mail; but e-commerce has led to a boon in packaging material, which is made, of course, from paper. You may be reading this on a screen, but paper remains almost everywhere in our lives.

Matthew Price is a regular contributor to The National.