I’ve been reading the extraordinary short stories of George Saunders for nearly 20 years, and one thing I’d never thought was that his warped, sneakily malicious and increasingly sentimental vision of 10-minutes-into-the-future America would ever seem particularly prophetic.

Saunders’s dystopian stories are about an America that is more re-enactment theme park or sci-fi, corporate-speak circus than functioning democracy. There were times I thought that Saunders’s America was a little over-the-top, a little too satirical and on the nose.

Then 2016 happened, maybe the least subtle year since 1933.

Turning on the TV, it was suddenly like the news was being written by Saunders. Donald Trump even talked as if he were a Saunders character: his all too revealing tossed word salad of venom, steely ignorance and neediness. Trump feels like the end point of an enraged, entertainment-saturated America that Saunders's short fiction has been mining for decades. Then, lo and behold, after four collections of short stories and a novella, Saunders's first novel, Lincoln in the Bardo, is a book about a President.

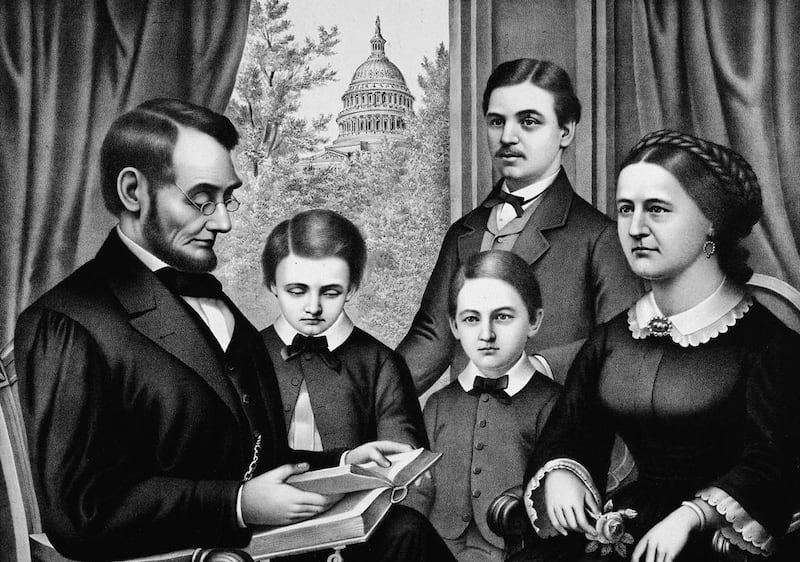

The prophetic Saunders of CivilWarLand in Bad Decline (1996) has stepped back from contemporary or future America and, seemingly, gone back to the actual Civil War and the last time the nation almost ceased to exist. Or, more particularly, the novel is about when Willie Lincoln, the 11-year-old son of Abraham Lincoln, ceased to exist after succumbing to typhoid fever in 1862.

Except, Willie Lincoln doesn’t exactly cease to exist. He wakes up in the Oak Hill Cemetery, surrounded by a Greek chorus of other spirits also caught between life on earth and whatever comes next. This is the bardo of the novel’s title, the transitional space that the Buddhists believe follows life on Earth, but precedes rebirth.

That the novel isn’t really about the Civil War, or even so much about Lincoln, was my first disappointment. How I wanted Saunders’s voice, after these last few months.

The novel operates like a cross between a film script and an oral history, much of it narrated by two woebegone ghost pals, Hans Vollman and Roger Bevins III. Other parts of the novel use actual quotes from historical sources mixed in with those created by Saunders to give an overview of the time. It must be said, given current events, that it’s hard not to see the novel as a kind of Twitter feed gone all literary and historical:

There in his seat, Mr. Lincoln startled.

roger bevins iii

Like a schoolboy jolting suddenly awake in class.

hans vollman

Looked around.

roger bevins iii

Momentarily unsure, it seemed, of where he was.

hans vollman

Like a lot of great works of literature, the novel teaches you how to read it while you’re reading it. It occasionally finds poetry in this mode of telling, and the liminal space it evokes can be both hilarious and chilling. And, too often, wearying. These spirits do tend to prattle on.

But Lincoln in the Bardo falls short of being a great work mostly because its concept never quite convinces. The point seems to be that these spirits can't move on because they don't accept that they're dead, thinking themselves only "sick". I found this central premise hollow. And when little Willie joins them, and for some reason, begins to be destroyed, the novel falls into some heavy-handed supernatural action sequences from which it's hard to care about the outcome. The threat never seems valid. Not once did I ever worry that Willie was going to be damned to the hell that Saunders has created for him.

But there are quiet moments in the near-constant ghostly babble, too. Every scene with the president, who visits his dead son’s corpse, are perfect, and achingly sad. Saunders’s Lincoln is a weighty and real creation. Here is an incredible display of empathetic and wise writing. Saunders’s Lincoln makes so much of the rest of he book feel half-baked, loud and aimless. If only the book were just about Lincoln. But, then, this might be a product of the terrifying new Saunders-like era we’re in: it’s hard not to read about a president such as Lincoln these days and not want more of him around. I’m not sure if we can entirely blame George Saunders for that.

Tod Wodicka’s second novel The Household Spirit was published in 2015. He lives in Los Angeles.