Heidi Simon wanted a Lambretta. She had won an amateur photography contest intended to celebrate the Marshall Plan in Frankfurt, and the 19-year-old Simon was lucky enough to have been awarded a Vespa scooter.

In the Germany of 1952, still recovering from the destruction of the Second World War, a teenager with a brand-new Italian scooter could count herself extraordinarily lucky, but Simon did not want a Vespa. "For the entire last year," Frank Trentmann tells us in his learned Empire of Things, "she had 'passionately' longed for a Lambretta", and she asked the officials at the ministry for the Marshall Plan if her prize could be a Lambretta scooter, instead of a Vespa. The ministry, less than interested in the private desires of its prize recipients, duly sent her the Vespa.

Drinking Colombian coffee while cheering on Brazilian footballers on our South Korean televisions, puttering on our American smartphones, driving our German cars while dressed in our Italian clothes, much of it assembled by Chinese workers, we might believe that we have entered a new era of global consumerism.

And with the idea of “consumerism” itself increasingly becoming an imprecation, implying a soulless community of short-sighted hedonists, all this stuff must be bad for us, right?

Trentmann sets out to prove us wrong with the stories of Heidi Simon and others, arguing for “an alternative trajectory that sees people as only becoming human through the use of things”.

He pokes holes in the classical economic model, in which rational consumers ensure their needs before proceeding diligently to satisfy their wants.

Sifting through six centuries of acquisitiveness, Trentmann reminds us that many of the essentials of contemporary life were once frivolous luxuries, transforming human behaviour through their acquisition.

Fifteenth-century Italians acquired spoons and forks and drinking glasses, their tableware, and their table manners, becoming ever-more specialised.

Nineteenth-century German prisons and hospitals made coffee, once an extravagance, a staple of their daily diet. And the advent of gas in English private homes made men more likely to eat their meals at home, rather than a pub, and helped to reduce housewives’ burdens.

The want of things is not a sad stand-in for culture, in Trentmann’s estimation, but the foundation of culture itself.

Goods also reflected the personal and political desires of consumers. Post-war Prague teenagers put American cigarette labels on their Czech-made ties, and Soviet boys fell in love with the hairstyle of American movie star Johnny Weissmuller.

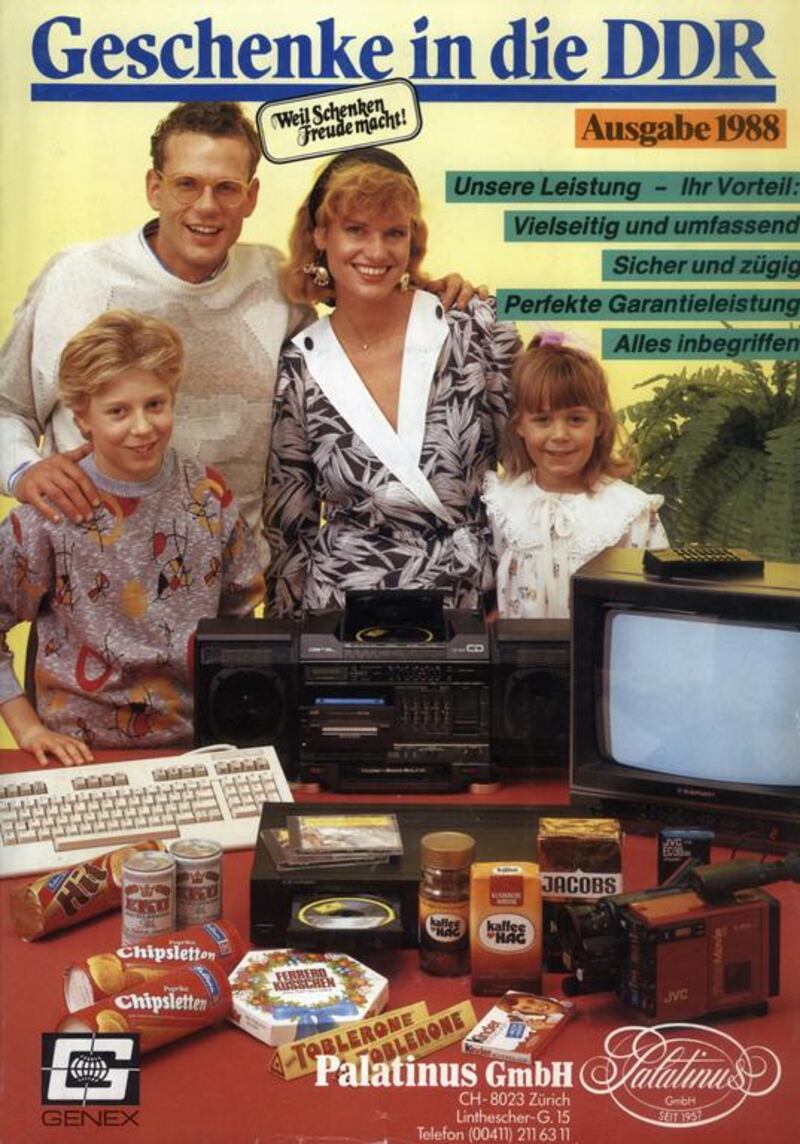

Even Communist countries had to provide their citizens with desirable consumer goods, like the East German vacuum-cum-coffee-grinder-cum-everything else Purimix.

And the collapse of the GDR came about, in part, because of how difficult it was to acquire those necessities, and how poorly-made East German products like the Trabant automobile were.

At its best, Empire of Things is a reliquary of stuff, and the myriad causes to which they have been put over time.

Trentmann is an endless repository of fascinating factoids, destined to be trotted out at dinner parties or on slow first dates. Did you know that in 1954, only one in 10 French homes had bathrooms? Or that the adoption of the washing machine encouraged German men to change their underwear daily? How about that the British National Health Service’s hospitals serve more meals daily than KFC and Domino’s Pizza combined?

Trentmann’s massive effort, boiled down to its own hard sell, might argue that consumerism, rather than a monolithic behemoth degrading local cultures and imposing artificial wants on its unwitting slaves, is instead always and ever local, personal and irregular.

Tradition and consumerism could interconnect.

Post-war Japanese families saved up for TV sets in order to watch sumo matches at home. The American-made Barbie doll was deemed inappropriate for girls in Muslim countries and was replaced by the Syrian-made Fulla doll, whose hijab was paired with high heels and lipstick.

And the onset of modernity is uneven. The massive department stores on the grand boulevards of New York and London and Paris, about which so much has been written, coexisted with peddlers’ pushcarts in the nearby alleyways.

Nineteenth-century Hindu merchants’ homes in Calcutta had Brussels carpets upfront for guests, and traditional exclusionary zones in the back for the rest of the family. And as the French middle classes discovered coffee, the working classes found it too, turning used coffee grounds and sour milk into a delicacy called café au lait.

Moreover, Trentmann is looking to reorient our understanding of consumption, asking us to wrench our minds away from the simplistic critique of worldly goods as a distraction from more essential concerns.

“We cannot simply stamp consumption as inauthentic or frivolous,” he says of colonial African culture’s embrace of consumerism.

“For former slaves and migrants, things were a great emancipator. A shirt, a hat, a watch and a mirror were tickets to social inclusion and self-respect.” Possessions could serve as an assurance of one’s place in the world, a guarantor of stability for those otherwise condemned to second-class status.

Empire of Things adopts a dual-use model, its first half a fairly straightforward chronological account of six centuries of consumption, and the second a more idiosyncratic study of the long tail of seemingly contemporary concerns such as local food and waste disposal.

The latter half feels notably less essential than the former and while Trentmann has some trenchant points to make about the way we live now, including an impassioned environmental call for less excess in our consumption, too much of it feels like a hefty appendix to an already-completed book.

Empire of Things is quite a bit longer than it needs to be, but its central argument is mostly persuasive. We make our things, and our things make us.

Simon knew what brand of Italian scooter she wanted, even as much of the city she lived in was still a bombed-out wreck. Like her, we are formed in part by our desires.

Consumerism is the stuff of our daily lives, from picking up milk at the grocery store to selecting a retirement plan.

While consumerism can be every bit as shallow as its “Gulag replaced by Gucci” detractors might have it, Trentmann’s historical perspective is an apt reminder that it can also serve the same broadening, humanising role as the higher pursuits of politics or ethics or spirituality.

We can buy clothes or support political campaigns as easily as we can purchase new iPhones. In fact, we can do those things from our new iPhones. And we can use those same iPhones to call our elderly grandmothers and offer solace to a grieving friend just as easily as we order dinner or browse Amazon for some wasteful trifle.

The Arcadian past, free of the desire for acquisition, is an illusion, and the consumerism-free future is, on closer inspection, a reawakening of the Christian belief that to lust for things is a mortal sin.

We are what we need, what we desire, what we want for others. “No ideas but in things,” argued William Carlos Williams, and we might go further and say, “no humanity but in things”.

Saul Austerlitz is a regular contributor to The Review.