"The war silenced me," Lebanese novelist Alawiya Sobh said in 2010, of her country's 15-year civil war. It took the novel Maryam Al-Hakaya (Maryam: Keeper of Stories) to help Sobh recover her voice. Or rather, "I invented Maryam to tell the story for me."

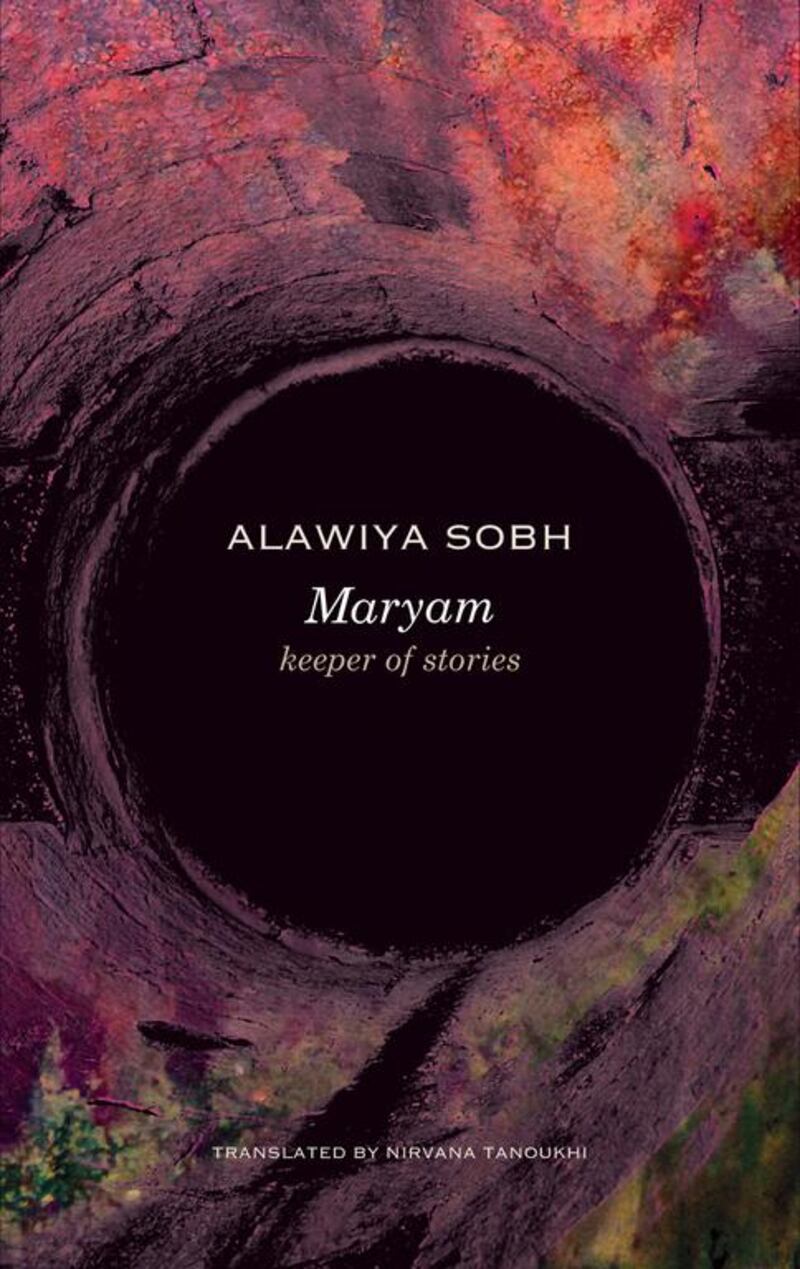

Sobh, born in 1955, had long been established as a journalist, poet, editor and short-story writer. But she didn't release her debut novel, Maryam: Keeper of Stories, until 2002, 12 years after the war ended. It has now been translated into English by Nirvana Tanoukhi.

Maryam’s conceit is compelling, if at times over-explained. The novelist “Alawiya” is turned into a background character while Maryam pushes her way to the foreground. Maryam complains that, after so many interviews with real and imagined people, Alawiya never collected her stories into a book. As the novel opens, Maryam has grown impatient: is Alawiya ever going to get it together?

Apparently not, because Maryam elbows the author out of the way and tells the stories herself: of her own life, her relatives, her friend Ibtisam, and occasionally Alawiya.

This novel doesn't just tackle the content of Lebanese women's lives. Its form – 1,001 Nights-esque, interlinked tales – is also womanish. The action doesn't follow the forward-marching masculine world of politics and business. Even when women protest or pick up weapons, the narrative stays focused on the circularity of relationships. The book also gives respectful attention to village superstitions, soap operas and other "low" genres associated with women.

Maryam is thus like Elena Ferrante's globally popular Neapolitan novels in that it places women's friendships at its centre. Although Maryam's women do have romantic (and unromantic) ties with men, it's the relationships between women – particularly Maryam and Ibtisam – that give the book its frisson.

Mother-daughter relationships are also central. Rather than being victims or saints, the mothers here are all too human. Maryam’s mother is taken into marriage against her will but she learns to fight back against her older husband in many different ways. The book has a wonderfully vulgar sense of humour, which only occasionally falls flat in translation, as when the phrase “no meaning” is too literally brought into English.

Aside from the occasional joke that doesn’t come off, the translation is clear and bright. It deals deftly with Sobh’s bursts of poetry, as when a dreaming character is struggling to get out of a coffin, “to free the birds in her eyes”.

Maryam’s mother gets some of the best lines. When Maryam’s mother would run after her daughters to hit them, “She would say in her heart: ‘May God, the Prophet and the angels guard you. May God’s name protect you,’ so they would not be hurt.”

Some of Sobh's narrative techniques are common to other Lebanese civil war novels, particularly the lack of a beginning or end, and the uncertainty of truth. In this, Maryam echoes novels like Elias Khoury's White Masks and Rabee Jaber's Confessions. But Maryam shines in its focus on women. Truth here doesn't shift because of different sectarian or class visions so much as the fight over women's bodies.

In particular, we see how Ibtisam’s truth changes after she marries Jalal. Ibtisam must completely reimagine her past, erasing Maryam, in order to accommodate herself to her husband’s values.

It also doesn’t matter, plot-wise, how Maryam’s father got his limp. Yet both of Maryam’s parents doggedly insist on the veracity of their story. We don’t know which is right – perhaps neither. What matters is that each character struggles to win ground by pushing their version.

For most of the novel, the character “Alawiya” stays to the background, just one among many. It’s only near the end that she retakes the helm and gives a few reflections on what it means to tell stories. The narrative then enters a strange in-between place where both Alawiya and Maryam are real and not-real, as when Alawiya says: “I feel Maryam poking me in the depths of my sleep to turn on the lights and listen to her talking.”

Indeed, it’s never quite clear who’s real and who’s not. Alawiya complains: “Who are these people who chase after me, demanding that I tell them their stories, when in the end they will only believe the tales they have told themselves?”

This question, about the book's original readers, doubly reflects the challenges of reading Maryam in translation. In the novel, we read tales that may be very different from our own. Yet somehow, we must believe them.

M Lynx Qualey is a freelance writer based in Cairo who blogs at arablit.wordpress.com.