India's jeunesse dorée, or wealthy young people, are best viewed - make that, only viewed - at night. During the day, these pampered youths slumber. At night they emerge in the luxury car that Daddy bought, to glide past slums where the poor sleep, exhausted from toil, to head off to a wild party where the carousing goes on till 5am, every day.

Before he went on a reality television show called Big Switch, which teaches spoilt brats the value of money and the difficulty of earning it, Sahil Rohira, 20, lived exactly that kind of life: no work, no household chores at his six-bedroom Mumbai home, summoning maids to fetch even a glass of water, never doing his own bed or laundry, spending Rs10,000 (Dh715) a week of his textile-manufacturing father's money on parties and sleeping all day until 6pm.

His only decisions were which of the 10 cars parked outside to use or what Louis Vuitton belt to wear.

"I'm an only child," says Rohira with a slightly sheepish laugh. "My parents have never said no to me for anything, not for as long as I can remember."

After taking part as one of the eight contestants on Big Switch, currently being shown on the UTV Bindass channel, he has emerged with an appreciation of his father's hard work and a new-found sensitivity to anyone who performs a service for him.

Rohira's exposure to the real world was a jolt. The concept of the show is that eight very rich kids are thrown together to live in a comfortable Mumbai bungalow with a pool - and no hired help.

Even their arrival at the bungalow was an eye-opener for the producers, who gaped as a young woman arrived with a pack of dogs, a dog-keeper and bodyguards; one young man rolled up in a four-car cavalcade. But these prima donnas have since had to fend for themselves - sweeping, cooking, washing up, clearing the rubbish, tidying their bedrooms and bathrooms. If they want comforts such as hot water, air conditioning, television, a music system or access to the pool, they have to go out and earn the money to pay for them.

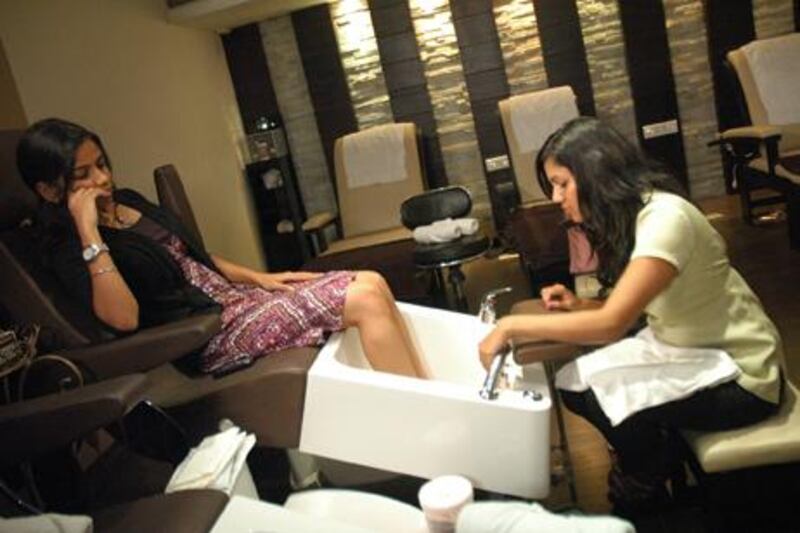

Rohira worked at a Marriott hotel, removing dirty towels and sheets from the rooms and getting them laundered. Another contestant, Heena Vasisht, 20, from Ahmedabad in Gujarat, took pizza orders and washed the feet of pedicure clients at a beauty parlour.

Others, stupefied, have found themselves working as waiters and couriers, washing cars and driving taxis. Remember, these are young people who might well never have been in a taxi or made a cup of tea and who are accustomed to splurging Dh1,800 on a meal.

"We wanted to show them how their parents earned their money and how the majority of Indians live," says the Big Switch host and former Miss India, Natasha Suri. "The change in them was dramatic. For the first time in their lives, they realised the dignity of labour."

In some countries, the extremely wealthy try to keep their children grounded, so that a life of privilege does not quench the fire in their bellies to achieve something. No such philosophy animates many rich Indians. Wealthy children generally exhibit a sense of entitlement. They display all the vanity and self-regard that come from their positions as daddy's darling.

"Don't you know who my father is?" is a common refrain if they ever find themselves unable to get a table or have to wait like ordinary mortals. If anything, rich parents tend to boast about the lavish lifestyles of their offspring.

This is why it takes a programme like Big Switch for rich youths to realise the importance of politeness and respect for their employees. What emerges is that they are not incorrigible. Suri said one contestant had been so tired delivering letters that he swore the next time a courier turned up on his own doorstep, he would offer him a glass of water and an appreciative smile.

After the shooting was over and Vasisht, who has been getting a car as a birthday present ever since she turned 16 and who enters the kitchen only when her mother begs her to "visit" it occasionally, went home and made a beeline for the staff.

"The first thing I did was hug my maid, driver and cook," she says. "I thanked them for everything they had done to make me happy. My parents were really taken aback."

She says that from now on, she will treat anyone with respect, the way she would want to be treated herself.

The contestants had agreed to take part in the show at the request of their parents, who had been contacted by the producers, although some insisted their parents "reward" them for their hardships. One young man asked for a Hummer SUV and another demanded a blank cheque, while a young woman wanted a trip to New York.

"It was wonderful to see their transformation," says Suri. "The boy who wanted a blank cheque returned it to his father. The boy who wanted the Hummer said he would rather earn it first and one girl gave the first salary she earned to her parents instead of spending it on air-conditioning her room in the bungalow."

Having experienced working at a hotel, Rohira has vowed never to leave a hotel room in a mess again. Nor to ask his maid to get him a glass of water, although he admits he still hasn't progressed to making his own bed. Moreover, his father is thrilled with the fact that he now rises at 10.30am instead of 6pm and that he has learnt responsibility, thanks to having delivered pizzas.

In fact, the most delighted people in the whole experiment are the parents. Keith Alphonso, the business head of UTV Bindass, says the programme is a "wonderful gift" from parents to a child. "It teaches them about the real world but without being harsh," he says. "It changes their perceptions for the better."

The channel has carved out a niche with youth reality shows that highlight the rich-poor abyss in India. An earlier series threw wealthy young men and women into a slum, where they had direct interaction with the area's dwellers, sharing a lavatory with 50 other people and living in unpleasant conditions.

Most of the contestants came out of that experience with flying colours, too. For Rohira and Vasisht, it has been satisfying to demonstrate to their parents that they are capable of working.

"I'm very glad I did it," says Rohira. "I respect myself more. If I hadn't done it, I would have been sleeping right now, in the middle of the afternoon, instead of talking to you."

When the programme ends at the end of February, Vasisht will leave with a small but meaningful insight. "The sleep you have after a hard day's work is different from the sleep you have after lazing around all day," she says.