As one of the world’s worst industrial disasters, India’s Bhopal gas tragedy of 1984 has all the makings of a magnificent and moving film: American corporate greed, a taciturn baddie, a bumbling government, emotional drama and a chemical that has attained immortality because, after killing and maiming thousands, it lives on to this day in the damaged organs of survivors and their children.

Until the director Ravi Kumar began work on his film Bhopal: A Prayer for Rain, no Indian filmmaker had tackled the subject, despite the fact that the horrific incident has haunted the subcontinent since December 3, 1984. On that fateful night, methyl isocyanate gas leaked from a Union Carbide fertiliser factory in Bhopal, killing around 15,000 people and causing birth defects in babies.

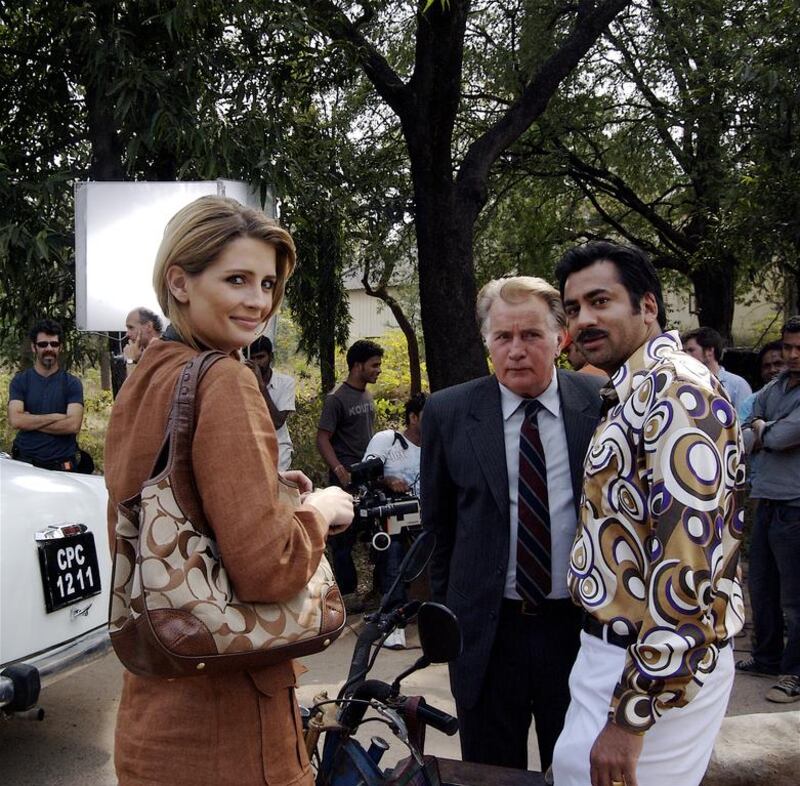

The film – with a soaring soundtrack by the Emmy-nominated composer Benjamin Wallfisch – will be released worldwide in the next few months with a stellar cast of Indian and American actors, led by Martin Sheen in the role of Warren Anderson, the infamous chief executive of Union Carbide, and Bollywood’s Rajpal Yadav, who portrays a worker caught in the tide of events. Also starring is Mischa Barton as the foreign reporter (Sienna Miller was initially cast but dropped out) who helps an Indian journalist (the American actor Kal Penn) raise his voice against the dangers of having a pesticide plant in the heart of a city.

The film, which was shot primarily in Hyderabad, Andhra Pradesh, depicts the events leading up to the disaster from the perspective of a rickshaw driver (Yadav) who lands a job at the plant. The hours are long but he needs the money and, in his desperation to keep earning a pay cheque, turns a blind eye to negligence on the part of the plant managers.

Kumar says the 30-year gap between the incident and his film has allowed him to maintain “a certain emotional distance from the tragedy”, helping him to objectively assess the events as they unfolded. Nonetheless, the facts that he unearthed on the sheer scale of the disaster shocked him.

“The city ran out of coffins,” he says. “The entire horse population of Bhopal was wiped out in one night. More devastating still is the fact that people are still suffering in what Bhopal victims call the second disaster.”

On September 29 this year, Anderson died in a nursing home at the age of 96 after three decades of living in seclusion. In Bhopal, the news of his death prompted some activists and survivors to celebrate.

Satinath Sarangi, of the Bhopal Group for Information and Action, said: “Hopefully, his life in hiding and ignominious death will be a lesson for all corporate criminals.”

But for Kumar, Anderson’s death does not signify closure. “His death makes it more imperative that Dow Jones [which later bought Union Carbide] do the right thing and apologise to the people of Bhopal and clean up the plant,” he says.

Sheen and Kumar had intense discussions about how Anderson should be portrayed. Should he be a villain with no redeeming traits? Or as a man caught up in a chain of events he had no control over? Kumar believes Anderson’s biggest flaw was not so much what he did but what he did not do in the aftermath, failing to take responsibility for the disaster, and not offering an apology.

Nevertheless, says Kumar, “we tried to give Anderson’s character dimension and depth, so that the audience would get to know what he’s thinking and let them make up their own mind”.

Sarangi’s organisation was involved to some extent in shaping the content of the drama. During the early stages of filming, Sarangi objected to the blame being laid on the Indian subsidiary of Union Carbide rather than on the parent company in the United States and on Anderson, but the issues were subsequently resolved.

Is Kumar worried that, three decades later, the film might be seen as irrelevant?

“Not at all,” he says. “Bhopal is as relevant as ever, given the fact that most industrial disasters have a similar chain of events leading to a perfect storm – negligence, cost-cutting, a foreign land and a lack of corporate governance.”

• Bhopal: A Prayer for Rain opens in Bhopal on December 3 and across the rest of in India on December 5; a UAE date has not yet been announced

artslife@thenational.ae