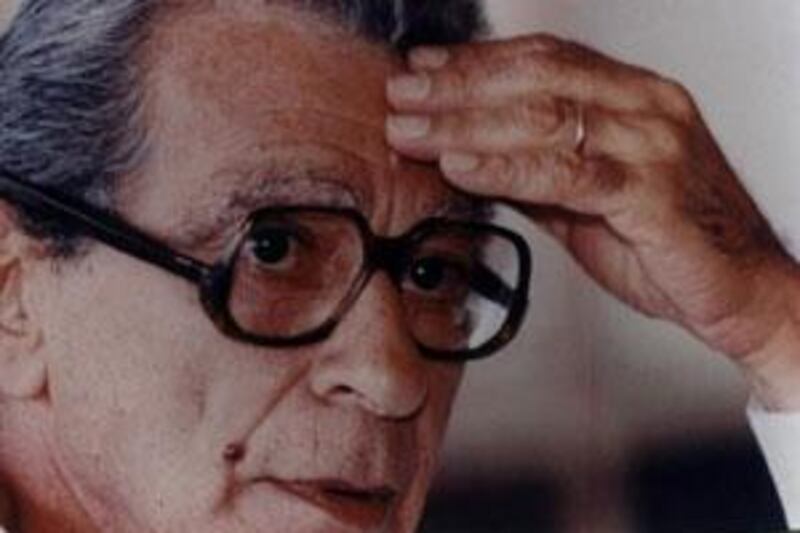

Youssef Chahine was one of the best-known filmmakers in the Middle East and - even more so - outside of it. A Silver Bear in Berlin; a life achievement award at Cannes; the bans on several of his movies, and the furious arguments over several others have all made sure of that. But was he also one of the best? Why did he alone, out of his many talented (some would say more talented) contemporaries, achieve such stature? Almost two years after the director's death in 2008, at 82, the evaluation of his work, its significance and its influence, continues.

In France - whose cultural establishment played a key role in anointing Chahine "the" Arab director - the town of Bobigny just screened every one of his 44 films, and issued a beautiful book of photographs, interviews, articles and summaries of his films. The festival celebrated Chahine as an international artiste, distinguished by his idiosyncratic style and humanistic ideals. Meanwhile, the American University in Cairo Press has published The Arab National Project in Youssef Chahine's Cinema, by the film professor Malek Khouri. Khouri writes that Chahine's "cinema sustained its political and national relevance by insinuating itself into sociopolital concerns ?" To Khoury and many others, it is Chahine's determined interventions in six decades of Arab history that make him interesting.

Chahine's films always had something to say on the political and social issues of the day. His explicit statements elicited, almost demanded, explicit responses in return - and continue to do so. At a panel marking the publication of Khouri's book, the director and longtime Chahine associate Khaled Youssef and the critic Samir Farid disagreed on whether Chahine was, in fact, an Arab nationalist. The former declared Chahine (whose family was Christian, of Lebanese origin) an Arab and Egyptian by choice, and a defender of Arab culture; the latter maintained that any form of nationalism was antithetical to the director, and that he was above all an Alexandrian. (Chahine was born in the coastal city of Alexandria in 1926, back when it was famously cosmopolitan, and under British occupation.)

Chahine started making studio films in Egypt's successful 1950s movie industry - black and white comedies and dramas, some of the first starring a wide-eyed Omar Sharif (whom Chahine discovered). In the 1960s he turned to nationalist melodramas: movies such as Jamila The Algerian (about a female resistance fighter in the Algerian war of independence) and The People and the Nile (a film about the construction of the High Dam, commissioned and ruthlessly re-edited by the Egyptian and Russian authorities).

One of his most popular films, still played often on Arab TV, is the 1963 The Victorious Salah Ed-Din. This state-sponsored movie is the Middle East's answer to the Hollywood epic, full of rousing action sequences and purposeful rebuttals of Western clichés about the Crusades. It is also - starting with its Arabic title, El-Nasir Salah Ed-Din - a thinly veiled paean to the Egyptian president Gamal Abdel Nasser. The Saladin of the film is just, clever and inclined to deliver speeches on the need for Arab unity; his right-hand man, Eissa, happens to be a Christian, and can therefore attest to the fact that Arab nationalism isn't the purview of Muslims alone; meanwhile, Saladin's enemies are traitorous, rapacious Crusaders in ridiculous wigs.

Chahine rued, in interviews, the rather simple political ideas expressed in many of his early films and his naive Nasser-worship. Yet several of his later films - which delivered messages against Western imperialism and religious fundamentalism - were hardly more subtle. Chahine was a secularist and a humanist, fond of saying things like: "I don't like borders. It's normal, I'm Alexandrian. I don't recognise borders of race, of religion, of colour, of any kind. I've fallen in love all over the place." His movies insisted on the possibility of understanding between East and West, Muslim and Christian (and Jew), woman and man (and man) - an admirable message but one that was often delivered heavy-handedly, sometimes almost disingenuously.

His 1997 film Destiny, set in medieval Andalucia, purported to be about the enlightened Muslim scholar Averroes, but this historical drama is aggressively ahistorical, an obvious allegory for contemporary Egypt. The forces of religious extremism are represented by a conniving sect that brainwashes its members by making them crawl through the desert; on the other side stands the humanist philosopher and a band of singing, dancing, life-affirming gypsies.

Particularly in his treatment of political Islam, Chahine was always polemical and caricatural, his Islamists a bunch of schemers stroking their fake beards. Chahine's uncompromising political stances are partly what made his name, but they also overshadowed his talents - and shortcomings - as a filmmaker. Today, the legibility of his films dates and mars them. And the critical enthusiasm in the West for films that present such simple analyses, and voice such unproblematic platitudes, seems almost condescending: "Look! An Arab humanist!"

Chahine has undoubtedly made some remarkable films. First and foremost, there is Cairo Station, a 1958 black and white masterpiece that takes place in the course of one day in Cairo's central train station. The film is masterfully directed, and Chahine also delivers a staggering performance as the pathetic anti-hero, Kenawi - a simple-minded newspaper salesman obsessed with the sexy, playful Hanouma, another vendor. Among the passing trains, the desires and dreams of Kenawi and many others circulate, intersect and collide. The movie's power comes from the energy, beauty - and ultimately, tragic violence - of all this motion.

His 1969 film The Land, about the efforts of poor farmers to save their plots from the development schemes of local notables, skirts melodrama but, thanks to its beautiful cinematography, affecting performances and unhappy ending, even its heavily symbolic sequences are imbued with emotion. And his 1991 short film Cairo as told by Chahine is a deft, loving tribute to the city that cleverly blurs the line between documentary, autobiography and fiction.

Cairo shows the freewheeling formal experimentation that became Chahine's other major trademark. After working in half-a-dozen different genres, the director began combining them all in single films. His Alexandria quartet - four whimsically autobiographical films, combining the personal and political - began in 1978 with the film Alexandria ? Why? Here Chahine wove together historical footage, a coming-of-age tale, surreal and farcical twists, dramatic psychological sequences, self-referential scenes about performance, and Hollywood-inspired musical numbers.

In Egypt these films reaped mixed reviews and little commercial success - the consensus is that Egyptian audiences couldn't keep up with Chahine's highbrow shenanigans. But there is no doubt that he was, in many senses, a trailblazer. He was the first Arab director to film on location; the first to make an autobiographical film; the first to feature homosexuals and to reference his own homosexuality (over which Arab critics passed with a resounding silence). He was clever, resourceful and utterly dedicated to himself as a cinematic auteur. By founding his own production company, and attracting foreign co-productions (with the Algerian and then French governments) he managed to keep making the movies he wanted to, even as the Egyptian state film system collapsed. He had a profound, inspiring and liberating effect on a generation of younger film-makers.

Yet his experience seemed to reinforce the dichotomy between commercial success at home and critical appreciation abroad. Chahine's is a problematic success story. His entire oeuvre is being stored at the Cinemathèque de France, but in Cairo you need to head to Shawarby Street, the city's DVD bootleg market, to find poor-quality copies of some (and only some) of his films. One young Egyptian filmmaker told me he was afraid of succumbing to what he called "Youssef Chahine syndrome": winning foreign awards for films that flop at the domestic box office. Indeed, Chahine's two most famous protégés have taken sharply divergent paths that seem to represent the limited options of Egyptian filmmakers: Youssri Nasrallah makes highbrow movies (sometimes brilliant, sometimes not) that young directors love and few go to see. Khaled Youssef makes bombastic films about "social problems" and racks up hits.

Chahine's own attitude was representative of the mixed feeling of "serious" Arab filmmakers toward their (often absent) audiences. On the one hand, he famously said: "I make my films first for myself. Then for my family. Then for Alexandria. Then for Egypt. If the Arab world likes them, ahlan wa sahlan (welcome). If the foreign audience likes them, they are doubly welcome." But he also said: "It's very troubling to enter a theatre to find [only] four guys sitting there ? What did I do it for? We live thanks to the public too. If you feel a political and social responsibility towards your public, you want them to leave the theatre with some values. Otherwise what's my purpose?"

It's a question many Arab film-makers are still trying to answer. Ursula Lindsey, a regular contributor to The Review, lives in Cairo