Walking into a darkened gallery at the Whitney Museum of American Art in New York, visitors to Sophia Al Maria’s first solo show in the United States are confronted by a large screen showing nightmarish visions of a shopping mall. A voice-over by the Hollywood actor Sam Neill intones “This is where the glamorous heart of evil is born”, as images of mannequins – given a sickly yellow tint – warp like reflections in a fairground mirror. Beneath the screen, dozens of mobiles, TVs and computer tablets lie junked across a bed of sand as they emit electronic squeals and show hyperfast images on a loop.

The effect is both disorientating and ominous – and that’s exactly how Al Maria wants it. To experience it, in her words, is like having a “bad trip”.

In her latest video installation, the Qatari-American artist has created one of her fullest examinations of the effect of rapid technological expansion upon Middle Eastern cultural norms. Of particular interest is the shopping mall and how these secular temples of capitalism have embedded themselves in the social fabric of Gulf nations; much like in the US where the mall was invented.

One video featured in the installation is called Black Friday in a nod to the biggest US sale day of the year, when shoppers spend US$4.4 billion (Dh16.159 billion).

Its partner, The Litany, sits beneath and underlines the way in which countries such as Qatar and the UAE have been catapulted into the hyperconnected 21st century. It shows the cost in terms of the physical waste that comes with being obsessed with owning the latest gadget, and the attendant information overload.

The video installation fits comfortably into the work of Al Maria, a 32-year-old filmmaker, photographer, director, author and journalist. More than a decade ago she was credited with coining the term “Gulf Futurism” to describe the sudden, almost overwhelming influx of modern technology, oil wealth and conspicuous consumption, layered on top of centuries-old tradition.

The idea of parallel existence forms the central strand in her well-received 2012 memoir, The Girl Who Fell to Earth, in which Al Maria describes splitting her time between her Bedouin father in Qatar and her American mother near Tacoma, Washington, where she was born.

The resulting cultural conversation is not a straightforward clash as one might suppose, as she explained to The National in 2013: "We're constantly told about these contrasting worlds but actually I think it's less of a big deal than we all think.

“There’s very little difference between certain conservative elements of American society and the Gulf, for example. And I think my father just felt very comfortable with my mother’s farming family. If people come from land, I think they instinctively understand each other, despite not having the same language.”

Her time in Qatar also allowed her to witness its transformation from a place where people "still keep goats and still make cheese in an inside-out sack", as she describes it in a interview about her Whitney show in The Guardian, to a shining, almost impossibly futuristic city.

Adding even more texture to her own cultural influences, Al Maria studied at the American University in Cairo and Goldsmiths, University of London, the city in which she currently lives.

The artist has previously exhibited at the New Museum in New York, the Waqif Art Center in Doha and the Townhouse Gallery in Cairo. Her writings include posts on her own blog and for the art title Bidou in which she has addressed, among other themes, the daily harassment and sexual violence that women endure in Egypt; this was also the subject of Virgin with a Memory, her first exhibition in Manchester, England, at the Cornerhouse in 2014.

As a rising star, Al Maria’s first solo show seems an appropriate fit for the Whitney, one of the hottest galleries in New York, which relocated before reopening in May last year.

The Whitney's galleries have an unreal, mirage-like quality that seems to fit with Black Friday and The Litany; curious visitors are drawn into the show by the sinister-sounding noises that periodically emanate from a room just off the main lobby.

The disembodied images of Black Friday conjure what Al Maria has called a "non-space"; one that is removed from geography and time. It's an unsettling but familiar feeling for the artist, given her peripatetic lifestyle.

As she once described in an interview about futurism in 2014: “I can’t tell if I’m in Hong Kong or LA or Dubai half the time when I walk into a mall. And that happens more and more these days because the mall is the dominant structure of a certain class group of which I am part. I literally find myself in malls, whether on holiday or on my way home from work or on a weekend even, and I am frequently confused as to how I even got there.

“It’s a place of weird pilgrimage in an era where to consume is to absolve yourself.”

The first images in Black Friday are a projection of two escalators from an opulent, as-yet unopened, mall in Doha.

Shot from the top down, they look two-dimensional and the effect is sufficently disorientating that it comes as a surprise when a man appears – walking backwards.

Over a speaker Al Maria can be heard telling a story about seeing someone she remembers from her algebra class in the US passing her in a Doha shopping mall.

Now a US serviceman, he does not immediately recognise her and she keeps quiet, moving on, because of what she calls the “insurmountable distance” between them.

Al Maria remarks: “I guess it felt like a bad dream.”

The screen cuts to psychedelic images of the mall, a baby’s head and a row of aeroplane seats, as Neill says in the voiceover: “This is where the glamorous heart of evil is born. And reborn.

“Not in the dark satanic mills of the 19th century but the bright fluorescent malls of the 21st.”

It is both a warning and some kind of sermon.

Later in the video, a man and a boy walk through the mall, apparently lost, as Neill talks about the “coursing ecstasy” people feel when they enter the building and start shopping.

Using a drone, Al Maria’s footage swoops the onlooker up through the mall, before using computer-generated imagery to remove the outer walls, replacing them with clouds and sky.

Black Friday acknowledges the undeniable, disorientating beauty that luxury shopping malls can have, whilst injecting a degree of horror that appears darkly comic at times.

The final sequence shows a veiled woman in black lying on the floor and reams of escalators, as if the woman has literally shopped ‘til she dropped.

As associate curator Christopher Lew notes in his essay that accompanies the exhibition, the mall is the embodiment of “the capitalist system that engendered it: one of endless choice without any escape...

"Likewise Black Friday is a closed loop; Ouroboros-like [a serpent that eats its own tail], the video's beginning is also its end with automated walkways that appear to go both up and down but lead nowhere, neither to heaven nor hell. The video captures a mall in limbo, in an unfixed state between near-completion and abandonment to ruin."

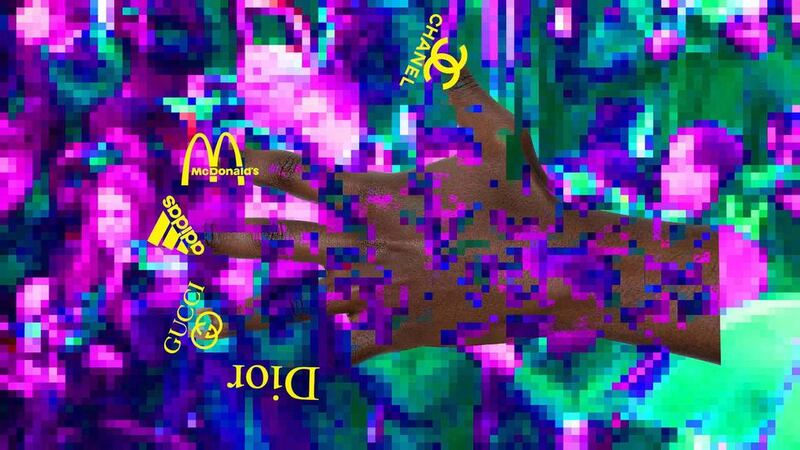

The Litany more fully explores what Al Maria has called her own "techno-pessimism", a mixture of J G Ballard and Jean Baudrillard with a geographical twist.

It brings to mind the work of Ryan Trecartin, a contemporary of Al Maria whose queasy videos give us a glimpse into a feverish, amphetamine-fuelled future, and filmmaker Adam Curtis, whose documentaries unpick secret social histories.

One of the TV screens in the sand shows a sheep in the foreground and logos of companies like Kellogg’s and MasterCard flashing up behind it.

Another screen shows footage of buildings being demolished, only the TV is upside down so they collapse upwards. Yet another plays a frenetic series of images of American soldiers, from the Iraq War.

This isn’t so much Gulf Futurism then, as the end of everything, an apocalypse of images and technology that is at once disturbing and powerful.

• Sophia Al Maria: Black Friday runs until October 31 at the Whitney Museum of American Art. Visit www.whitney.org

Daniel Bates is a freelance journalist based in New York.