If good things come in small packages, Willard Wigan’s works are nothing short of phenomenal.

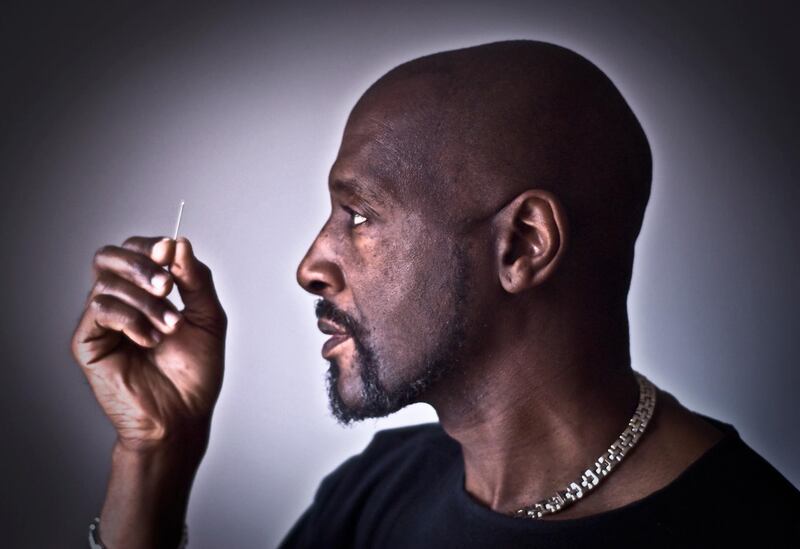

Wigan, 61, carves sculptures that cannot be seen, in all their glorious, colourful detail, with the naked eye. They have to be measured in micrometres (one of which is equal to a millionth of a metre), and some are smaller than a blood cell. Fans of his work have called it "the eighth wonder of the world", and in recognition of it, he was made an MBE in 2007 in honour of his services to art. In fact, Queen Elizabeth II loves his work so much, she commissioned him to create a sculpture for her Diamond Jubilee celebrations in 2012. "I was invited to Buckingham Palace to bring the crown to the queen," Wigan says.

That wonderfully detailed Coronation Crown sculpture is placed atop a pinhead.

The artist set a Guinness World Record in 2013 when he sculpted a minuscule motorcycle from a fleck of 24-karat gold scraped from a chain and placed it in the eye of a needle.

He broke that record when he carved an even smaller sculpture of a foetus from a piece of carpet fibre and placed it inside a strand of hair plucked from his beard.

Wigan’s entry into the world of tiny art began 56 years ago when he was a five-year-old living in Wolverhampton in the United Kingdom and it was born from a need to escape. “I had a problem with learning to read and write,” he says. “I wouldn’t call myself illiterate. I just have a learning difference.”

Willard’s “learning difference” is that he has Asperger’s syndrome, but this remained undiagnosed in the early days. “Teachers didn’t know about autism, so I was used as an example of failure,” he says. “They would take me around the school and tell the kids about me. I become an exhibit, which was traumatising.” He recalls running home and hiding in the garden shed.

“My mother was a disciplinarian and if she hit you, you’d see more stars than Patrick Moore,” he jokes. “You’d become an astronomer because you’d see that many stars. So I didn’t want to get caught.” But it was getting caught (though thankfully not hit) that revealed his talent for making small things. In the garden, his dog unearthed a colony of ants while digging holes, and he decided to make them a place to live, as well as a palace for the queen ant. “I really did think they were just like little people. I used to sit and have a conversation with them to see if they’d talk back. Of course, they never did,” he says with a laugh.

When Wigan’s mother saw what he had made, he says she was in a state of disbelief. “She said, ‘You make these little things, when you get older, your name will get bigger. The smaller you make them, the bigger your name will become. If you throw a grain of sand into the sea it will create a tidal wave of success. And that tidal wave will take you on a journey’,” Wigan says.

And that’s when his journey began. He’d carve Beatrix Potter characters on to the head of a toothpick and show them to his mother, who would tell him they were too big. “I wanted to please my mum and see how small I could actually go,” he says. “It became an obsession.”

Secondary school was no easier for Wigan. “I couldn’t get any confidence off the teachers because everything I did was wrong,” he says. “I became very quiet because I felt that whatever I said didn’t matter – I lost me.”

But then he got his hands on a microscope. “Looking at things through it I noticed that I could see quite clearly, and I thought, I can go smaller now. So I started experimenting with making sculptures I could put inside the eye of a needle, or on pinheads. I was 13 years old. I was really developing,” he says. “I found me.”

Taking his art smaller was almost a reflection of what was happening to him at school. The smaller he felt, the smaller he carved and the more he withdrew into himself. “I used to want to disappear; I wanted to be invisible, because I hated what was happening to me but I didn’t get bitter, I got better,” he says.

The sheer scale and detail that Wigan is now able to achieve under the microscope is astonishing. “When I do exhibitions, I see people looking through the microscope and they can’t believe what they’re seeing,” he says. “Even scientists and people in the world of nanotechnology can’t believe what they see. Surgeons are now approaching me wanting to know how I do it.”

Wigan has immortalised Usain Bolt and his famous lightning-strike pose, Barack Obama and his family and Harry and Meghan Markle, inside the eye of a needle. In his carving of the Statue of Liberty, the pedestal on which Lady Liberty stands is carved from a single grain of sand.

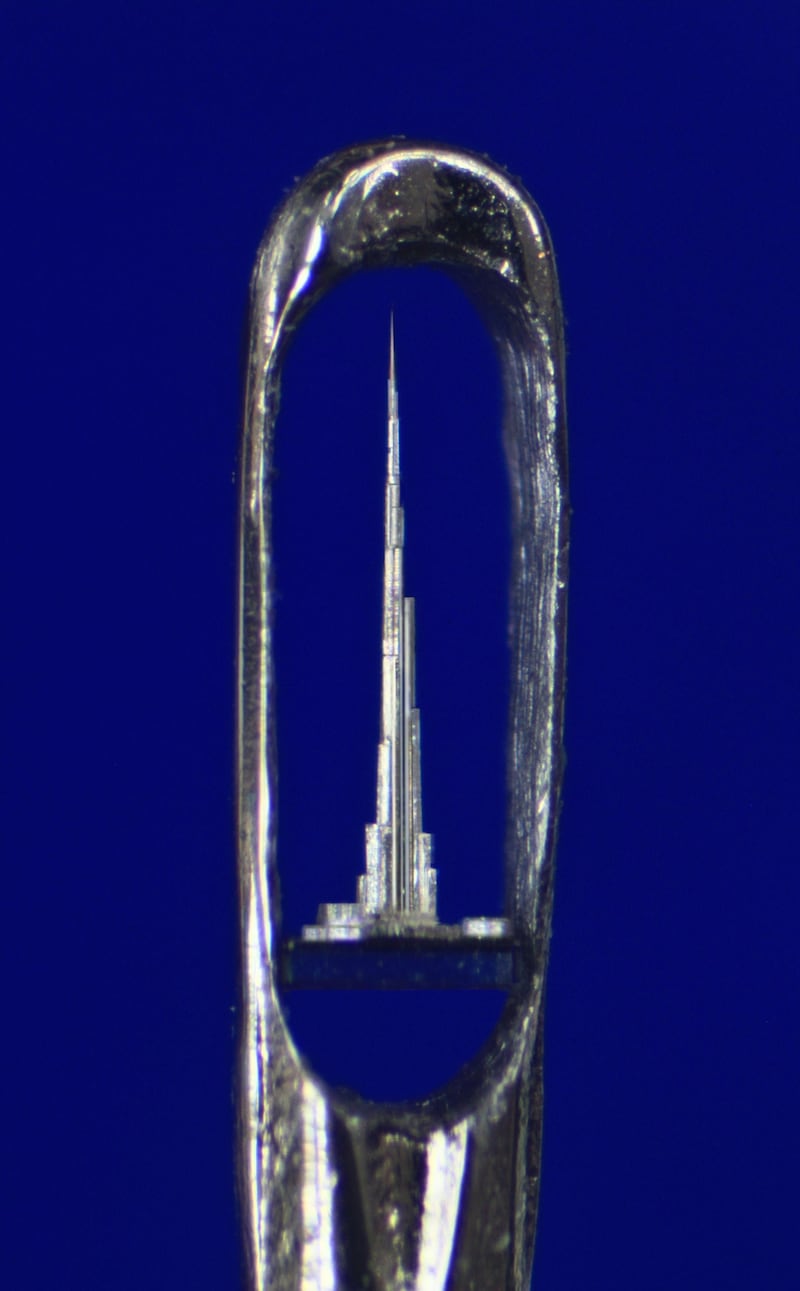

Also impressive is his sculpture of the Burj Khalifa. He has managed to replicate the instantly recognisable and intricate flower-like shape of the building, its stepped silhouette and its precision as it tapers to a point that seemingly pierces the sky. It’s depicted in shiny while gold, and is no bigger than a full stop in this newspaper. And he made it in just four weeks. “I flattened a small chain link and cut it up into microscopic sections,” he says. “It was very complicated because it was so thin and tiny.”

He says he lost the first attempt. “I couldn’t find it, but then I looked under my fingernail and it was there. I took it out and it wasn’t quite right so I did it again.” After three attempts, he was happy with the end result. “I knew it would be impossible for me to make it look like the real building, so I’ve done a suggestion of it. There will be some imperfections, but I’m very proud of it because I succeeded in making it look as much like the building as I possibly could,” he says.

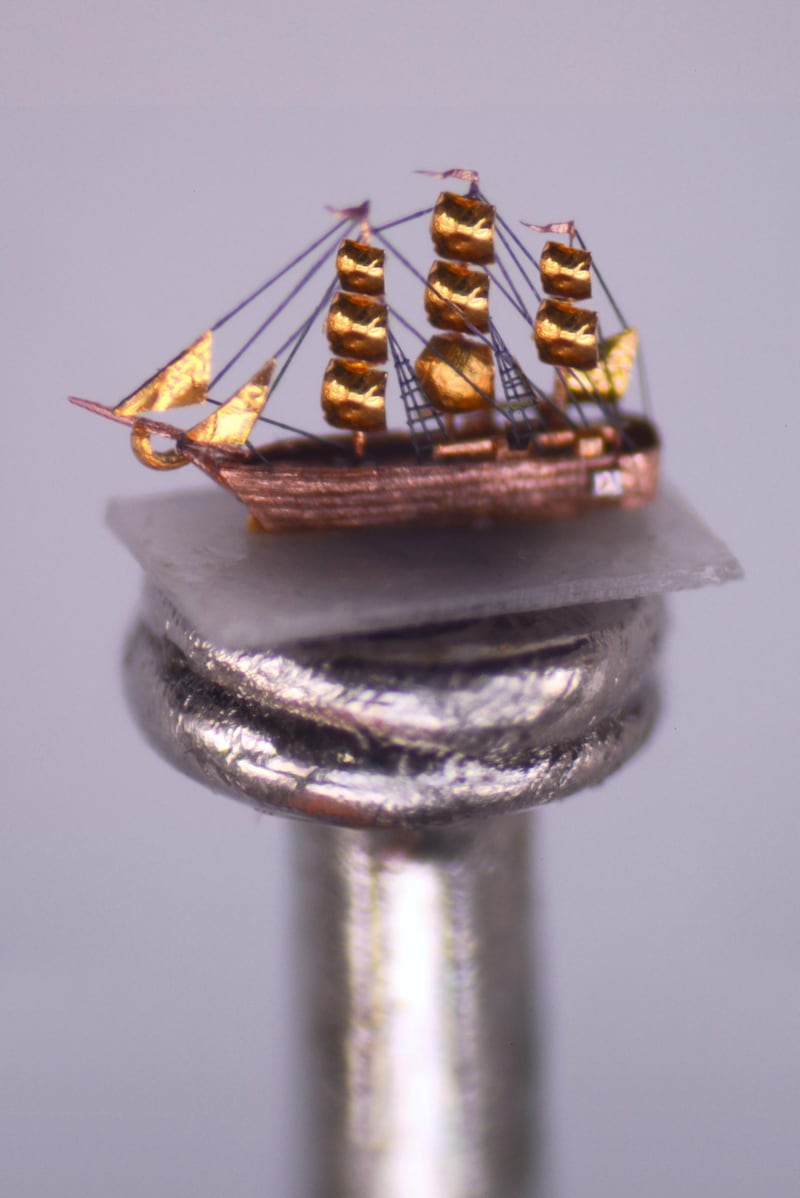

Another standout piece is of a ship he made, complete with several sails and rigging. It’s constructed entirely from rose gold and 22k yellow gold, and it’s smaller than a full stop. “I shook my socks and little fibres came out, which were floating through the air. I grabbed those and that’s what I used to rig the ship,” he says. The micro-sculptor marked the 400th anniversary of Shakespeare’s death with a statue of the Bard set within the eye of a needle captioned, “To see or not to see.” The piece is made of Kevlar, the material used to make bulletproof vests, and the frame around the words is of 24k gold.

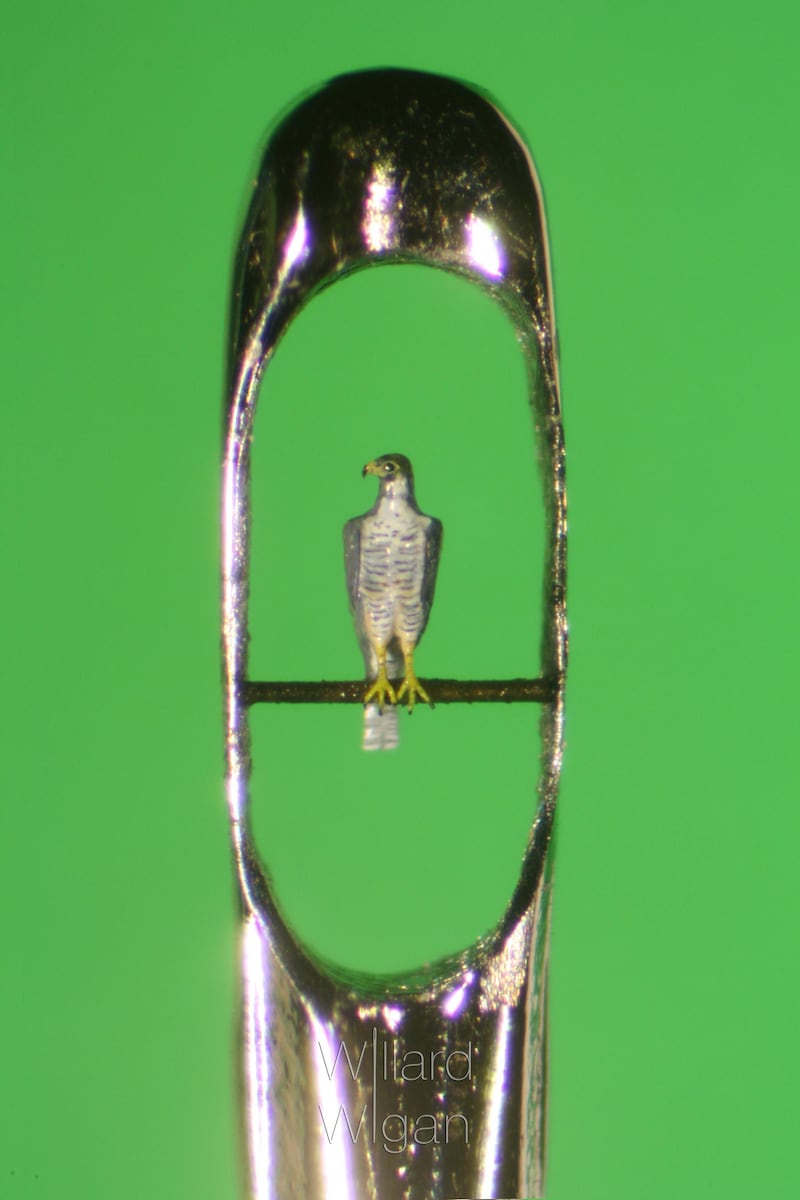

It took Wigan about three weeks to complete because he was working on two other pieces – a ship and characters from Frozen – at the same time. He has also created a striking rendition of the UAE's treasured national bird, the falcon, and has placed the Taj Mahal on a pinhead. He has even put a procession of nine camels inside the eye of a needle, although now, he says, "If I wanted to, I could put 20. I've got a lot better".

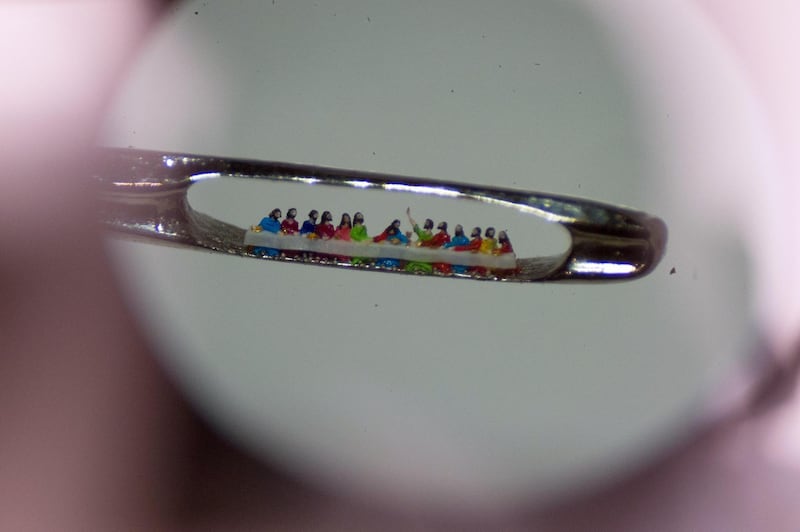

Wigan's favourite piece is a sculpture of Leonardo da Vinci's The Last Supper – Jesus and his 12 disciples individually carved and placed behind a table complete with dinner plates and the Holy Grail, all set within the eye of a needle. It took him seven weeks to complete – the longest it has taken him to finish and his most challenging piece to date. "I was going mad," he says. "I used a piece of Kevlar, cut it up and constructed it. The table is made from a thin piece of nylon, and all the pieces are individually sculpted and put behind the table. The Holy Grail and plates are made from 24k gold. And I painted all of them with an eyelash," he says.

Because his sculptures are so small, the skill and dexterity with which he must work has to be extremely controlled. "I started to learn to breathe properly," he says. "I'd squeeze my fingers together to stop the pulse from moving my finger. Then I stared to hold my breath, and I found that each time my pulse stopped, there was more stability." He also makes his own tools that are small and sharp enough to carve with precision under the microscopic. These include sharpened needles, fine bits of razorblade attached to toothpicks, and shards of diamond. "When I wake up in the morning I get a magnifying glass and look on the pillow for eyelashes. They become my paintbrushes," he says.

Having to work painstakingly slowly between his heartbeats is physically as well as mentally challenging. Does he enjoy it? “I’ve trained my nervous system to make sure that my hand is so still that it couldn’t be a pleasure any more,” he admits. “It only becomes a pleasure when I’ve finished.” But there have been plenty of mishaps on the path to completion. “On the disc under the microscope I had this tiny piece of dinner plate that I broke off to make a yacht. I was chipping it with a piece of diamond and it jumped and disappeared. I was looking for it for about three or four hours and I couldn’t find it. I started to cry,” he says. “I went into the bathroom to wipe my face. And on the end of my nose I saw this little white speck. I got a piece of blu tack and touched it on the end of my nose. I put it under the microscope and there it was; my sculpture.”

When making the Mad Hatter's Tea Party scene from Lewis Carroll's Alice in Wonderland, he had made all the characters, the table, teacups and teapot. He was about to paint Alice when a sudden intake of breath meant he inhaled her, instead. But Wigan has never given up. "I could be working for 15 or 18 hours a day, and even though it's driving me mad, I still do it, because I'm honouring my mother's words," he says.

In the future, he plans to sculpt Martin Luther King and Rosa Parks – "people who made a big difference during the civil rights movement in America", and anyone who has done something significant in the world. "I've got to miniaturise them as a big tribute," he says. He also plans to bring his works to the UAE. A date and a venue has yet to be booked, and his team are keen to hear from, and collaborate with, art galleries and museums in Abu Dhabi and Dubai to make this happen. "It would be a dream for me," Wigan says. "Because words, really, are no good; people have to see the work for themselves. Seeing is believing."

Wigan is an inspiration, and he says that’s all he hopes to be. “I wanted to inspire kids with learning differences; inspire people who believe that they cannot become what they want to. This work is very punishing, but it’s because it’s so small that it has a really big message.

“Human beings always use the word nothing,” he says. “But there’s no such thing as nothing. It’s the little things that can make the biggest things happen in our lives.”

And for Wigan, that’s true, times a million.

For more on Wigan and his creations go to www.willardwiganmbe.com

_______________________

Read more:

UAE memorial artist Idris Khan on the 'overwhelming' nature of making award-winning Wahat Al Karama

Louvre Abu Dhabi’s new exhibition: Japanese and French cultures explored side by side

From humble beginnings: this Palestinian museum in the US has big ambitions

_______________________