The Silk Road. The name alone conjures up visions of bounty-laden caravans travelling to distant locations, saddlebags full of riches like gold, ivory, spices, incense, and of course silk, all ready for the trade or raid, whichever came first. The Silk Road was not one long paved caravan superhighway; it was made up of many routes. Northern stretches and southern passages carried soldiers, traders and even Marco Polo himself from Rome all the way to modern-day Xi'an in Western China since the second century BC. These routes also helped the transmission of theologies over the difficult mountain passes, carrying Islam to non-Arab lands until the 15th century when a sea route from Europe to Asia was discovered.

When Islam arrived in the cities along the routes, it brought its own artistic tradition as well. Calligraphy, architecture and replications of the Quran a mingled with the local cultures of central Asia, the Far East and the Levant. The 11th annual Sharjah Islamic Arts Festival is a tribute to Islamic art from the countries that made up the former Silk Road, from Syria and Uzbekistan to Iran and China. Instead of displaying historical artefacts, the festival shows off artwork from the modern and contemporary periods. All of the art, whether it be calligraphy or video, bears the mark of those Arabs who spread Islam along the Silk Road.

The festival is too large for a one-day visit; it's so large that the emirate's Art Directorate has spaced programmes for the festival out over the course of a month and a half. The bad news: the festival's programmes are all finished. The good news: the exhibits are still showing until October 10, so there is still time to experience the multitude of Islamic-influenced art and video from former Silk Road regions that is on display.

The eight separate exhibitions that make up the Islamic Arts Festival were selected for a purpose. "We chose them because it's a new way to use calligraphy in design and their social motifs," says Hisham al Mazloum, the festival's general coordinator. In the 20 years that he has worked at the Sharjah Directorate of Art, Mazloum says he rarely saw the museum shift focus from Arab countries to other Muslim countries. "We did a little on these countries, but not like this before."

"The Silk Route is an integral part of Islamic history," says Charles Pocock, an expert on ancient and modern Islamic art who is an official adviser to the Abu Dhabi Music and Arts Foundation (ADMAF). "It was like a throbbing vein - a jugular through the Islamic world. " The various galleries present a microcosm of the Islamically-influenced post-Silk Road world. The city-states and counties that emerged along the route combined their own traditions with those of Arabian Islam so well that today they appear to be seamless. Farsi calligraphy uses Arabic letters and fonts; Chinese red lacquer looks perfectly at home in a mosque's interior. Even the red pigment in the lacquer is a combination from the Middle and Far East. Its base is made with the sap of dragon's blood trees (Dracaena cinnabari) endemic to the Yemeni island of Socotra, which surely made its way to China via the Silk Road.

The two "must-see" parts of the eight exhibits, which heavily cover Central and Eastern Asia, are the Iranian posters and the Chinese photography displays. The Iranian posters, all of them dating from the 1960s and onward, are clean and sparse with their use of script, a change from traditional Arabic calligraphy. There are posters for music festivals, theatre festivals, poetry festivals ? even posters for poster festivals.

"The Iranian graphic design pieces are interesting because of the huge influence they have in the region," adds Pocock, who points out that the exhibition features works by a number of well-known Iranian designers who unfortunately get precious little wall-time at galleries outside of Iran. The Sharjah Art Museum's display of over 130 posters will remind those who think of Iran only in terms of today's rhetoric of nuclear armament that the country's populace is both globally aware and extremely sophisticated, something that is articulated in contemporary Iranian graphic design.

One poster by Sadeg Barirani from 1967 references the iconic 1896 Don Quixote poster by the Beggarstaff Brothers by using the same shadowing and colour blocking techniques. Only in Barirani's print, the poster advertises an Iranian folk dancing program at Roudaki Hall with a white figure atop a mirror image in indigo on a cobalt background. This technique creates a damask pattern in the blue-on-blue silhouettes, building on the inventions of its less visually lush 19th century predecessor.

Another work by Taraneh Saheb from 2003 commemorates the 100th anniversary Sadeq Hedayat's birth (Hedayat was a celebrated Iranian short story writer and is widely considered to be a national treasure). Saheb's poster for the exhibition uses thumbnail reproductions of other posters from the exhibition arranged in a way that they create a shadowy portrait of Hedeyat emerging from the background. Saheb, herself a "grande dame" of Iranian graphic design, uses the same technique in her Hedayat poster's design as the American artist Chuck Close uses in his oversized portraits. Saheb, along with a host of other Iranian graphic designers including Barirani, clearly still inform their work with western artistic traditions, though they use them as another tool in their box in order to create uniquely Iranian design. As far as their Islamic-ness goes, it's unclear how these posters are religiously orientated in the traditional sense, besides their origination in a Muslim country.

That is less of a conundrum for the richly coloured portraits of Chinese Islamic life captured by Haji Mohammed Bai Xue Yi, a photographer and professor in China's central Henan province. Bai is known at home for his photographs of Muslim life in the Arabian Peninsula and has mounted solo shows featuring shots of Oman and his pilgrimage to Mecca. Here, Bai depicts the colourful street life - and the serene religious life - of Chinese Muslims. Pictures like Xichuan Mosque in Guanghe, Gansu Province, are photographed in colour but almost look like they were printed in all sepia. The terracotta spires and dome of the titular mosque rise in the foreground against a hennaed sunrise along the mountains that frame them. Gansu province, which runs from Mongolia to Central China, is at the heart of the Silk Road and is considered one of the cradles of Chinese civilization. It also has a large Muslim population, featured prominently and proudly in Bai's photos.

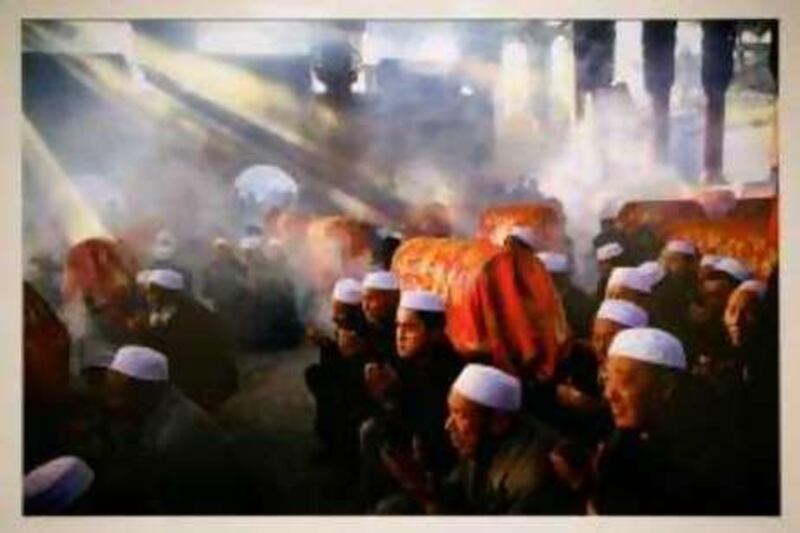

In Make a Du'a (informal prayers) a photo of Chinese men praying in an open-air mosque while light streams in on them, there is a palpable spirituality. Other photos of the same series, all taken in 2007, show the mixing of Arab Islamic culture and Chinese heritage. Plug into the Incense is a photo of mourners at a funeral hoisting a giant stick of incense that is twice their size into an even larger copper pot filled with sand in front of a mosque as others look on. The mosque is not domed as in the Middle East but tiered like traditional Chinese architecture. Though burning incense at a funeral is more often associated with Buddhist tradition, the oversized incense stick here is green - the colour of Islam.

Chinese and Arabic cultures have influenced each other since before the time of the famed travelers Ibn Battuta and Marco Polo. "Islam was brought through to China on the Silk Road," says Pocock. "And the central themes of Middle Eastern renaissance were borne out of the influx of Chinese ceramics brought through the Silk Road." The two cultures undeniably share a reverence for calligraphic art and are known for their elegant scripts.

"The Silk Road was very important to the exchange of cultures and facilitated understanding," says Mazloum. "And old writing in Chinese has something Arabic in it." The rest of the shows in the festival are worth checking out if you've got the time, but the lack of explanations, background or historical significance of the works certainly dampens the desire. The space itself is beautiful though, and there is a plentiful amount of work from lands of the Silk Road displayed in the museum's various galleries. As Pocock says, "there's something for everyone there."

swolff@thenational.ae