According to Rudyard Kipling, “East is East, and West is West, and never the twain shall meet.” However, the German poet Johann Wolfgang von Goethe saw things differently, envisioning not just a meeting, but also a mingling:

“Who knows oneself and others

Cannot fail here to find

That Orient and Occident

Are forever intertwined.”

More specifically, Germany and the Arab world are linked and united through a variety of shared values and common features — one of which is storytelling.

Inside the exhibition

A special, first-of-its-kind exhibition at the Neues Museum in Berlin examines this rich cultural heritage. Presented in German, Arabic and English, and consisting of more than 100 artefacts, Cinderella, Sindbad & Sinuhe: Arab-German Storytelling Traditions is a fascinating display of hugely influential literature ranging from ancient texts to the tales of the Brothers Grimm and One Thousand and One Nights.

A number of small yet perfectly formed sections provide insight into how certain stories have been able to transcend spatial and temporary boundaries and chime with other cultures. In addition, they trace the archetypal themes and universal motifs which both underpin and interconnect German and Arab narrative traditions.

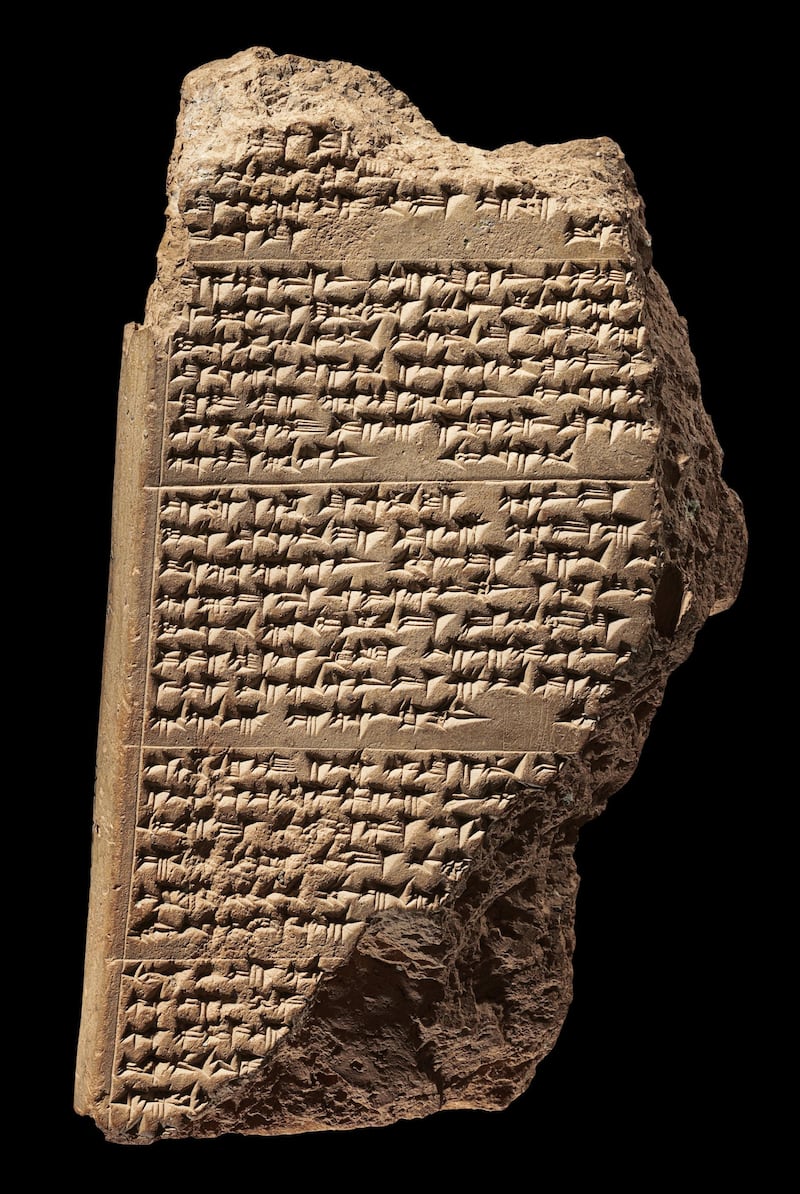

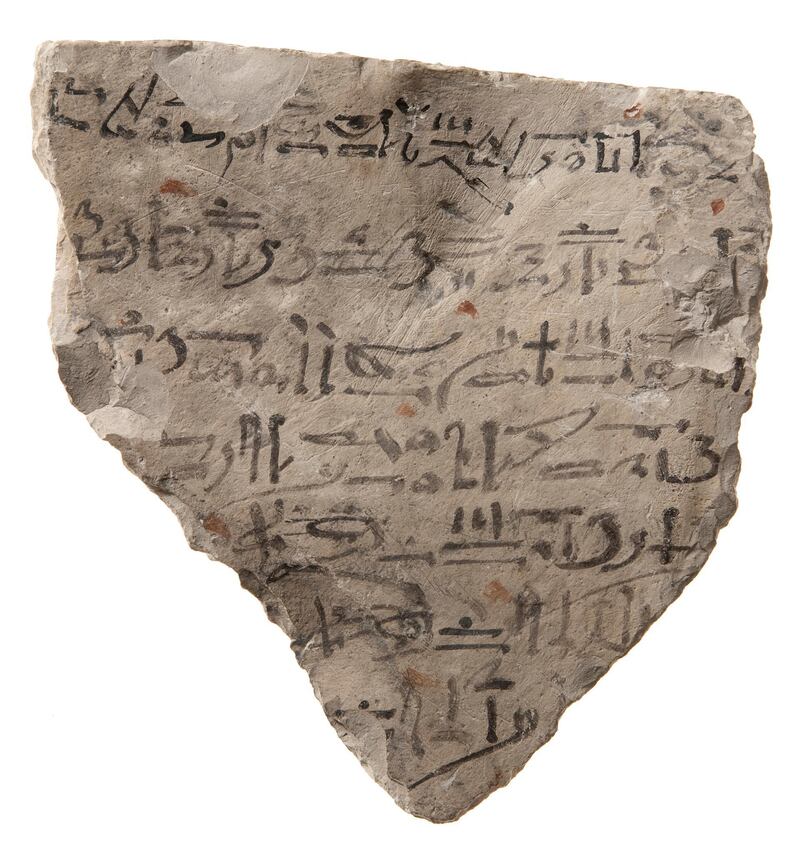

The first section showcases some of the earliest surviving examples of written stories, most of them dating back more than 4,000 years. There is a cuneiform tablet of the Mesopotamian poem The Epic of Gilgamesh and a limestone ostracon with parts of the Ancient Egyptian story of Sinuhe.

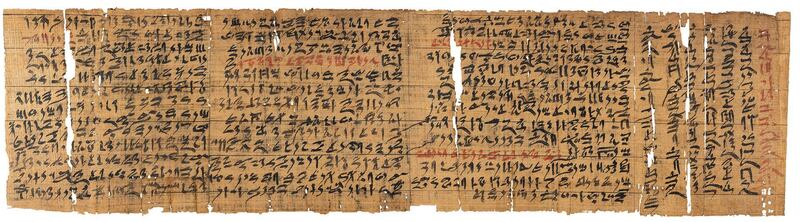

Also from Egypt are several fragments of papyrus manuscript containing excerpts in black and red ink from the Tale of the Eloquent Peasant, The Story of Ahiqar, and Papyrus Westcar. Some of these tales were channelled or repurposed in the 20th century by both a German and an Egyptian Nobel laureate — Thomas Mann and Naguib Mahfouz.

Another section is devoted to the journeys of stories. An explanatory note informs us that the study of tales and storytelling throughout history has usually been a consequence of diplomatic, military or scientific missions.

Alongside a stunning Arab-Ottoman map of the Arab and European world from 1738, and a miraculously preserved Arabic papyrus exit visa dated 722, we see a selection of the travel reports of Ibn Battuta (1304-1368). No diplomat, military man or scientist, this Tangier-born traveller journeyed far and wide of his own accord — and indeed on his own.

The influence of the Brothers Grimm

Perhaps the most absorbing sections are those which focus on the diverse content and enduring appeal of two seminal collections of stories. There is an impressive array of rare manuscripts and editions of the Brothers Grimm's Children's and Household Tales and One Thousand and One Nights, plus an original writing set from the household of the former and various objects inspired by the latter: records, film posters, postcards, and an Egyptian oil lamp, like that in Aladdin.

The exhibition’s director, Verena M. Lepper, stresses the importance of the stories which the Grimms painstakingly collected and edited. “They mark a significant shift in the transition from a primarily oral tradition of storytelling to written forms of tales in Germany,” she says. “They influenced artistic work profoundly, both in Germany and worldwide, and served as a key reference point for the majority of future tale collections.”

One Thousand and One Nights gave rise to many German spin-offs designed for German audiences, all of them featuring an idealised "Orient". Goethe engaged with Arabic and Persian language and literature, and displayed here are his clumsy, yet clear Arabic writing exercises from 1816, and his famous work — Faust and the West-Eastern Diwan — which taps into not only One Thousand and One Nights but also the verse of the tenth-century poet al-Mutanabbi.

A series of sections explore those narrative tropes and notions that are common to both Arab and German storytelling, some of which developed as a result of cultural exchange. Animals play an important role, particularly in fables, and so one section groups together the classic fable collection Kalila wa Dimna (presented here as a slick touch-screen interactive display) and the farcical tales from the thirteenth-century itinerant German fabulist Der Stricker.

Similar themes through cultures

A similar section deals with a much loved comic staple, the wise fool. "They have the important function of suspending social restrictions and providing a space to think about taboos," says Lepper. Here, he is represented by the German Till Eulenspiegel and the Arab Juha, both of whom were supposedly modelled on real-life fourteenth-century people.

Lepper argues that the wise fool is often portrayed as an anti-hero. "They lack the conventional heroic qualities of courage, idealism, and morality. The hero of a tale has the opposite function: his or her courage, strength and morality serve as an ideal for society." A section on heroes juxtaposes the Taghribat Bani Hilal with another epic, the Nibelungenlied.

We find more of the same in sections on sleep, good and evil, and, intriguingly, the shoe. "With the fairy tale Cinderella," says Lepper, "variations of which can be found all over the world, the shoe advanced to one of the most important symbols mostly associated with beauty and wealth."

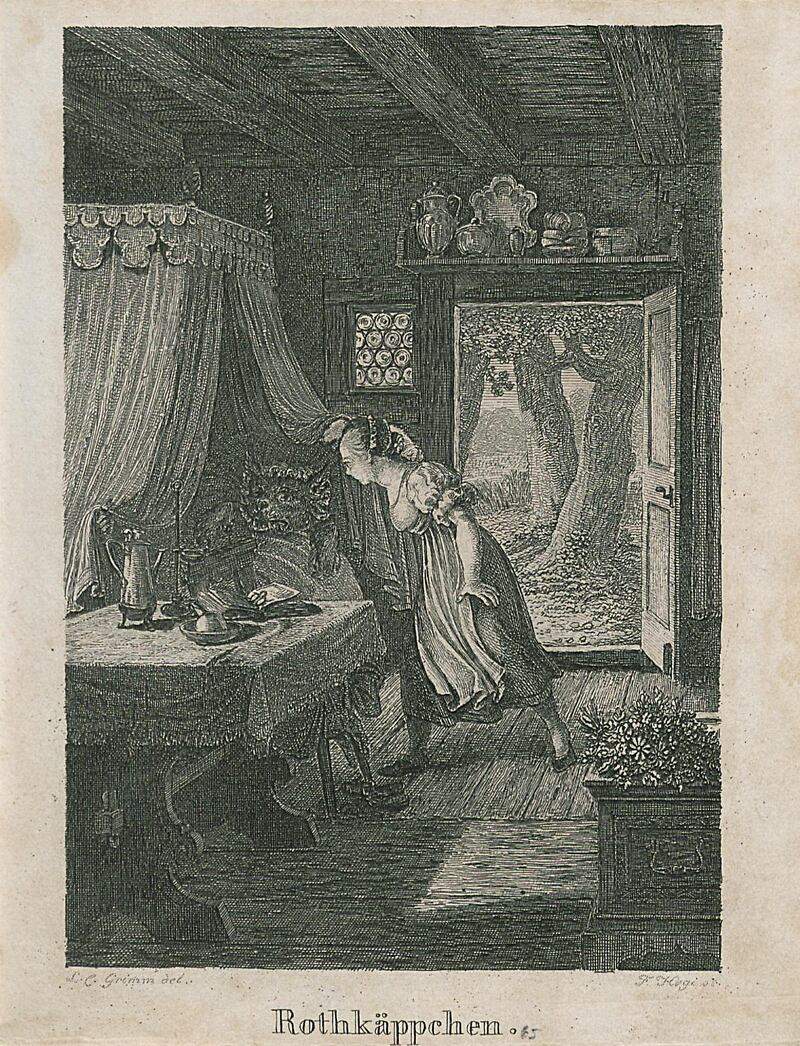

Comparing and contrasting German and Arabic variations of stories proves to be a constant pleasure. A modern Arab version of Cinderella exhibited here, Hamda and the Fairy Fish, revolves around a girl of lowly origins who is sent by her stepmother to scale a fish. Elsewhere in the exhibition, we come across another contemporary update: next to Layla and the Wolf, the Arabic counterpart to Little Red Riding Hood, is a copy of the Lebanese Layla and the Wolf and the Telephone, in which the canny eponymous character uses her mobile phone to be rescued by the police. "This clearly demonstrates how international tales and fairy tales are," says Lepper. "They travel through the world and get adapted, changed and retold."

This magical exhibition doesn’t just celebrate the art of storytelling. In this age of demarcated differences and divides, it also serves as a valuable reminder that stories can change hands, cross borders, and, for all their variations, provide a vital source of connection.

Cinderella, Sindbad & Sinuhe: Arab-German Storytelling Traditions is at the Neues Museum, Berlin, until August 18. For more information, visit www.smb.museum