Lucian Freud was a still a teenager when he learnt arguably his most important lesson in painting. As the Second World War broke out across Europe, he attended Cedric Morris's East Anglian School of Painting and Drawing. And it was Morris who taught him that a portrait could be "revealing in a way that was almost improper".

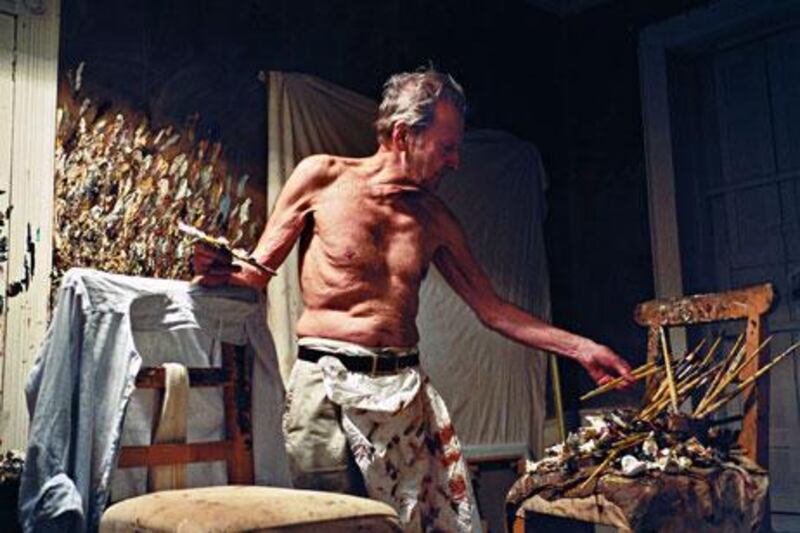

Freud, who died last week aged 88, certainly took heed. His work, often featuring layers upon layers of bulbous flesh, was realistic to the point of being disturbingly unsettling. But this bohemian grandson of the psychoanalyst Sigmund Freud had a style so earthy, inimitable and unique, his paintings became instantly recognisable. And sought after.

It's doubtful whether, in anyone else's hands, a nude portrait of an obese civil servant lolling on a sofa would have set the record for the highest fee paid at auction for the work of a living artist. But in 2008, Roman Abramovich stumped up a staggering $33.6 million (Dh123.4m) for Benefits Supervisor Sleeping, while its subject, Sue Tilley, still worked at the job centre.

Freud painted a whole series of Tilley portraits, and it's their forensic, unsparing and merciless detail which is so confrontational - and so characterised Freud's artistic career. Painting the blank face of a famous person wasn't for him - Freud initially learnt his trade by studying his wives (he married twice), friends and family. Girl With a White Dog (1951-2), shows a woman whose dressing gown is slipping from her shoulders, a dog on her lap. It's tempting to say the beautifully rendered animal comes out of the piece better: the woman was his wife Kitty Garman, and they were divorced just a year later.

As Freud's reputation grew, so did the status of some of his subjects. But the unflinching style remained. His series of paintings featuring the larger-than-life performance artist Leigh Bowery is like a collection of grotesques, but Bowery's outsize humanity still shines through. In Naked Portrait 2002, a pregnant Kate Moss looks spectacularly bored. And, most notably of all, Freud was not cowed by convention when he painted Queen Elizabeth II. Unsurprisingly - and thankfully - this wasn't a nude, but the thick lines in her face hark back to that first piece of advice from Cedric Morris. Many thought it "improper", with The Sun newspaper calling for Freud to be "locked in the tower" and The Times saying "the neck would not disgrace a rugby prop forward".

It's not a traditionally beautiful royal portrait, but it did get beneath the skin of its subject, revealing a life marked by service and duty. There's a wonderful photograph of the queen sitting for Freud, looking hilariously nonplussed, crown balancing on her head. Freud captures some of the inherent absurdity of royalty in the portrait, too.

Freud, then, was not only one of the greatest realist painters of our times, but had no immediate rival as a portrait artist. Not, of course, that painting is a competition - although he was nominated for the Turner Prize in 1989, losing out to Richard Long. But his death does pose serious questions about the state of portraiture in 2011. In many ways Freud, working right up to his death, was keeping the form alive and interesting. Certainly he influenced it in myriad ways.

Last year, for example, Daphne Todd won the prestigious BP Portrait Award for her haunting, almost shocking painting of her dead mother, painted at the funeral parlour. Todd said she found a beauty in the painting (and somewhat flippantly said that it was easy, because her mother "kept still"), and in many ways she was following in Freud's footsteps: in 1989 he produced The Painter's Mother Dead the day after his mother Lucie Freud died.

The 2006 winner of the Portrait Award also had reason to thank Freud: Andrew Tift won the prize for a triptych of Freud's first wife, Kitty Garman. And in 2009 Peter Monkman was heralded for a spooky portrait series of his 12-year-old daughter. The style is not recognisably Freudian, but the idea - to try to understand his family through paint - certainly is.

Freud's daughters from many relationships (he has at least 13 children, but the actual figure is unknown) regularly sat for him - sometimes nude, unsettlingly. One of them, Isobel, once said in a documentary: "Each time I did a picture with him I swore I'd never do it again, but I then do because it is a way of having a relationship with my dad."

So it might take some time for someone to fill the void left by Freud's death. The German artist Gerhard Richter is often called the best living painter, and his blurry, imprecise portraits of anonymous families are genuinely fascinating - as are the two famously intriguing paintings of his daughter Betty. But Richter will turn 80 himself during a major retrospective of his work at London's Tate Modern in October. As the current holder of the BP Portrait Award, Wim Heldens has received well-earned attention.

But his work has a quietness and solemnity that is unlikely to attract multimillion-dollar auctions in the future. One of the other nominees this year, Louis Smith, is more interesting: a Manchester artist who has trained himself to paint like the old masters but used a very obviously 21st century model-like pose in his submission. It would be fascinating to see how he approached Kate Moss.

Smith's paintings have little of the realism of Freud - there are no dilapidated sofas or flabby bodies in his work. But perhaps the different approaches of Heldens and Smith are to be celebrated: every generation finds its favourite portrait artist because, in the end, every generation loves the piercingly intimate reflection on life that portraiture offers over straight photography.

Lucian Freud, though, was more than just an icon of late 20th-century art. His work - like that of the great Cézanne, Durer or, of course, Leonardo da Vinci before him - is likely to be timeless. Roman Abramovich is probably thinking $33m was a pretty good deal.