With more than 2,600 auctions under his belt, Hugh Edmeades knows how to make a sale. In his 35-year career as an auctioneer for Christie's, he has brought in more than $2.75 billion (Dh10bn) in bids for at least 310,000 lots that have included fine art, jewellery, antiques and classic cars.

Among the most notable are the collections of the late Princess Margaret and Elizabeth Taylor, Eric Clapton's guitars, a Stradivarius violin that sold for $2.7 million and a wooden cabinet attributed to Thomas Chippendale finalised at more than $3 million.

Edmeades’s profession is one that requires a combination of performance, attentiveness and salesmanship, which the British auctioneer has honed over the years. Growing up in a home furnished with antiques, he joined Christie’s in 1978 to become an antiques dealer, but eventually the company pushed him to conduct auctions. He started training in the 1980s, a time, he says, when “the market was very strong. Everyone was buying, so life as an auctioneer was easy. All you had to do was call the numbers as quickly as you could because there were so many hands going up.”

But with the advent of online auctions and a shift in consumer tastes, things began to change. The issue is twofold: not many people physically show up to auctions any more, and lots have reduced in number. "At the time, I was probably selling 300 items every week. Nowadays, the auctioneer is lucky if they get 100 items a month," he says.

In much the same way that e-commerce has hit traditional shops, the same trend has affected the art market. "There are fewer items and people are far more selective now with the advent of eBay. People are buying more online and, certainly, Christie's has been doing more online auctions around the world. Time is money, so it's easy for buyers to sit in their offices or homes and just click a button to send bids," he explains. Over the years, the antiques market especially has taken a big hit. "Modern is what everyone wants. People also can't afford the big houses to accommodate the big furniture," he says.

Edmeades has experienced these shifts first-hand, beginning with the arrival of telephone bidding, and, eventually, online streaming to bidders around the world. While he has had to adjust to this new technology – engaging with the camera and calling out to unseen audiences in the virtual realm, for example – his auctioneering style remains the same.

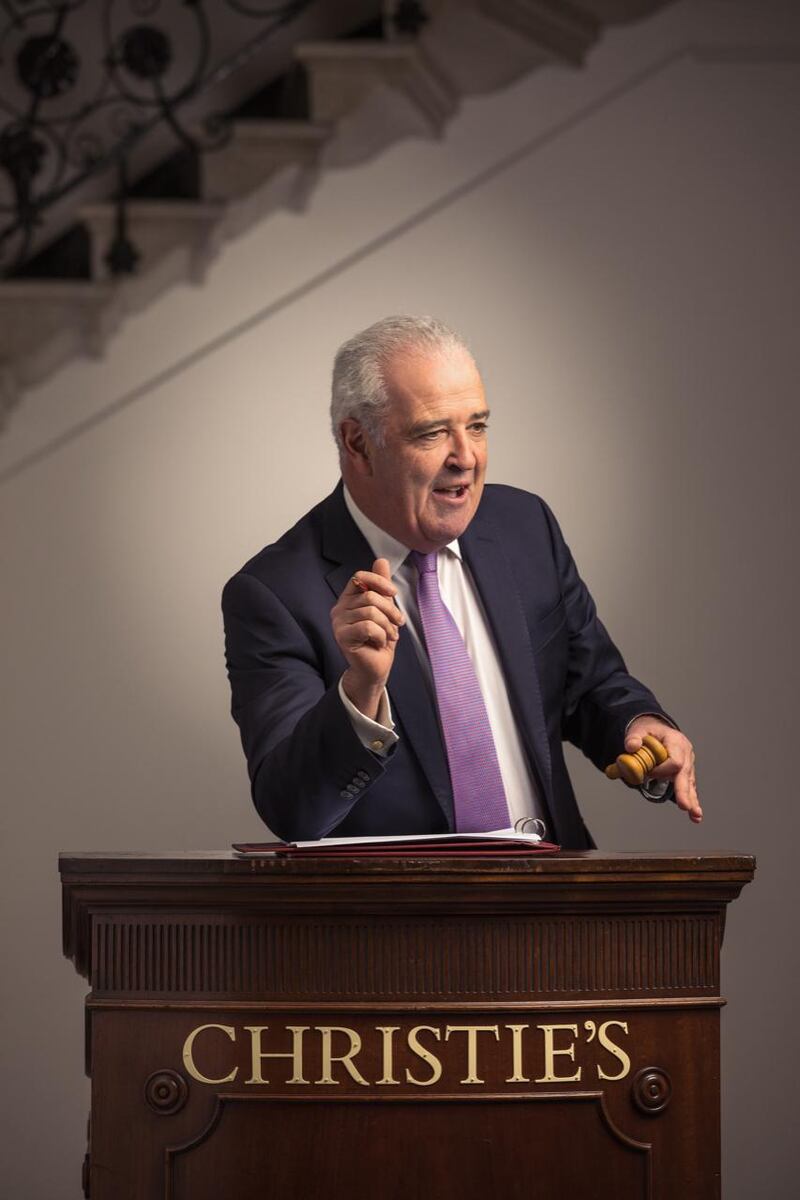

“I try to make it fun,” he says. “I’m energetic and lighthearted, even though it’s a serious business we’re doing. You don’t have to be a stand-up comedian up there, but you have to show that you’re not just some money-grabbing robot.” When he’s behind the rostrum, Edmeades, who usually wears a dicky bow or a bright tie, commands the room with his booming voice.

He acknowledges the performative nature of auctioneering, and has even trained with actors to help infuse each bidding with theatrical elements. “We’ve got to give them a show,” he says.

Before each auction, he meets Christie's specialists to identity the most significant lots and the best buzzwords with which to describe them. "Auctions are often fast and furious, so I don't read out the whole description. I pick out key points that I hope will make someone go one more bid than perhaps they might want to."

During these auctions, some psychology is also at work. "I've learnt a lot about body language over the years – people might be shaking their heads, but still holding their bidding number. So there's probably at least one more bid in them." At the same time, Edmeades knows his state of mind affects the sales, too. "If you're lethargic and listless up there, it will reflect in the audience as being lethargic and listless with their bidding. No one wins."

There's a great deal of concentration and quick thinking from his end, too. He also knows that the auctioneer navigates much of what happens during a sale, keeping track of bids from the floor, the telephone lines and the offers online. The way the auction goes depends, in large part, on his attitude and energy, which he needs to sustain for hours.

"In the back of my head, I'm not just representing Christie's. I'm representing the vendor, all the staff who've got a piece consigned, the ones who have done the research, the photography, the marketing, the ones bringing the pieces from the warehouse to the storeroom, and even the doorman who's opened the door to the bidders. An awful lot of people go into the moment when I get up, and if I'm not on good form, all their hard work isn't maximised," he explains. He also tries to maintain a sense of fairness to the process. He notes that as fast-paced as auctions might go, he ensures that he gives potential buyers a fair chance to consider their bids before bringing the hammer down.

Stepping back from his full-time role at the auction house in 2016, Edmeades has taken on more charity auctions. In 2008, he was the auctioneer at Nelson Mandela's birthday gala in London, which brought in $5.6 million for Mandela's children's charity. He was in Abu Dhabi last month to raise money for an initiative of the UN refugee agency to provide health care to refugees in Lebanon.

Edmeades also conducts training programmes for aspiring auctioneers, though he notes how the profession has become increasingly competitive. "We've got enough auctioneers, but not enough sales," he reiterates. That means fewer opportunities for young auctioneers to build their experience, but it also means that the ones who do make it have to stay in top form. As the market continues to shift and even newer technology appears, it seems that auctioneers such as Edmeades are the last of their kind.