From tomorrow, time travel will be possible in Abu Dhabi. On Saadiyat Island, in the space of a few minutes, you will be able to traverse two million years of history, thanks to a new exhibition presented by the British Museum.

In collaboration with the Abu Dhabi Tourism & Culture Authority, the museum has compiled an exhibition under the title A History of the World in 100 Objects, which began life as a BBC radio series in 2010. The museum is the consultant for the launch of the Zayed National Museum, set to open in 2016. The museum is the consultant for the launch of the Zayed National Museum, set to open in 2016.

Starting with an Olduvai stone chopping tool from early human ancestors in the East African Rift Valley and ending with a solar lamp, designed to give some of the world’s poorest people access to safe, non-toxic light, the premise of the show is to reveal the myriads of histories of the globe through careful examination of a few chosen items.

Becky Allen, an exhibition curator at the British Museum, has spearheaded the project that has taken a year to put together and has enlisted the help of 90 other curators, and includes pieces from all departments of the London institution.

“The whole idea of the exhibition is to celebrate the fact that objects have a unique storytelling ability and that there are many things we learn from the close study of a single thing,” she explains.

“It is presented in a chronological timeline and to be able to walk through history in one space is very exciting.”

Although the list of objects was put together in 2010, the collection that is being displayed in Manarat Al Saadiyat until August is not exactly the same, with changes being made particularly with more recent items.

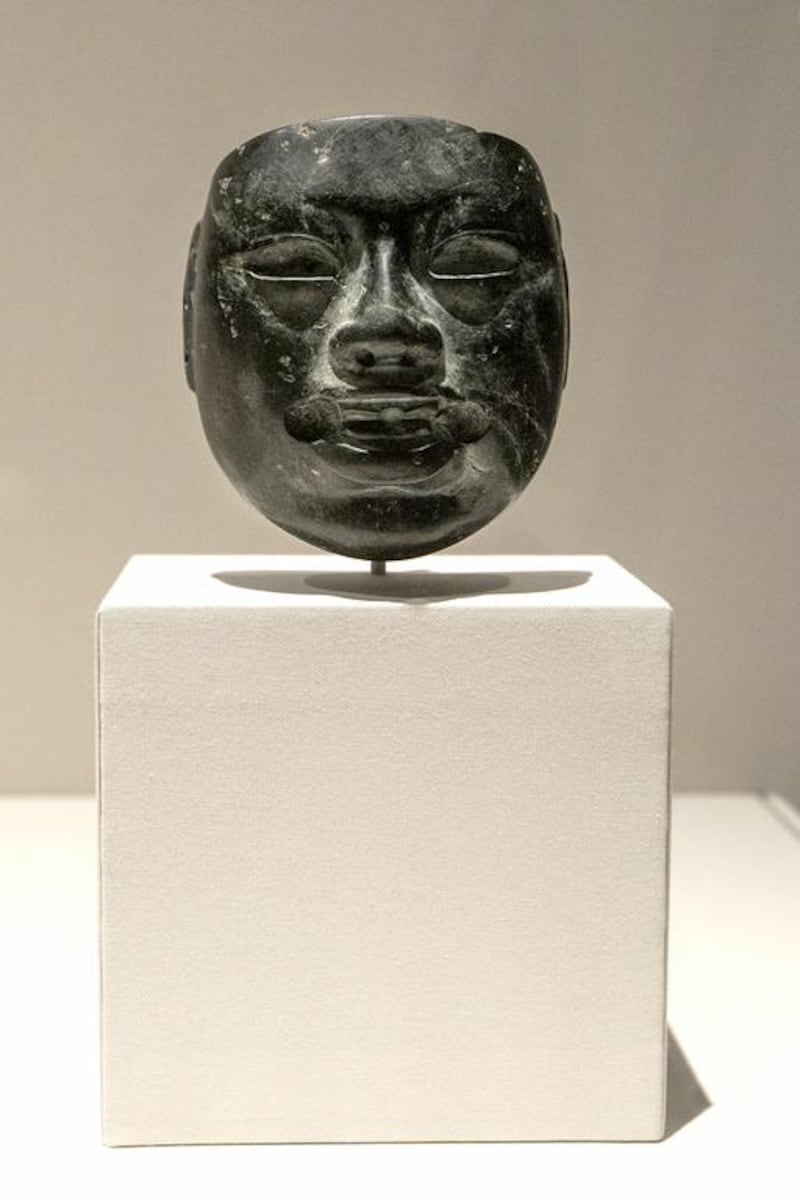

There is an attempt to spread the items geographically, which gives the effect that Neil MacGregor, the director of the museum, describes as “spinning the globe”, so that the viewer jumps from the stone tools of the early humans in Africa to flint points from the people of North America to pottery made in 5000BC in Japan.

Then there is a pestle from Papua, New Guinea, showing that humans prepared food before eating, giving them a competitive advantage over other mammals, and a burnt bowl from northern Iraq, an item that demonstrates wealth because it was seemingly burnt on purpose.

The stories that are entwined with each item are incredibly inspiring and the accompanying text and contextual images help to give the viewer direction.

Perhaps one of the most famous objects in the exhibition is The Flood Tablet from Mesopotamia. Dated at 600BC, it is a writing tablet from the library of the Assyrian king Ashurbanipal and is part of the epic of Gilgamesh.

“It is talking about early literary writing, but it is also really interesting because, in this particular fragment, it tells a similar story to that of Noah and the flood, even though it predates scriptural accounts by about 400 years,” says Allen. “It is therefore talking about commonality in storytelling traditions, which is an important element of human history.”

From about the same period, there are also the coins of King Croesus, which are among the first ever coinage and are the beginning of the story of money as we understand it today. When bearing in mind the effect of trade in the modern world, these tiny objects, bearing the symbols of a lion and a bull fighting, are of huge significance. Later on, we see Islamic coinage from the reign of Caliph Abdul Malik and then later still, in the section devoted to the Medieval period, we see one of the first pieces of paper money from China.

Interestingly, in object No 98, this story is brought right up to the present day with the display of a Sharia-compliant gold credit card from HSBC.

“We had to continue the story,” explains Allen. “This card itself also tells a story. It is a Sharia-compliant credit card from the UAE, but from an Asian bank and bearing the symbol of an American company, Visa. It also displays the lack of tangibility of money nowadays, that it doesn’t need to be seen any more for trade.”

It is this democratisation of objects, where a credit card is given the same importance as a three-metre stela from ancient Egypt or a Roman sarcophagus from medieval England that makes this exhibition a brilliantly executed piece of work.

Even if you are underwhelmed by the centuries of history captured in the folds and turns of the objects, you will probably do a double take when you see a Didier Drogba shirt hung up inside a glass case as object No 99.

“It is there for its international qualities,” says Allen, explaining that it is a Chelsea Football Club shirt, which is a Russian-owned club in London, bearing the name of a footballer who grew up in the Ivory Coast and who, after London, went on to play in China and then Turkey. The sponsor of the club is Samsung, a Korean company and the actual object is a counterfeit shirt, made in Indonesia and sold in Peru. The accompanying map underlines the global reach of one seemingly mundane shirt.

Before you leave, a prototype foot-controlled car designed by a student from the UAE University in Al Ain closes the exhibition as piece No 101. It is a conclusion to the long story and the perfect symbol that Allen chose to show that the story never ends.

“Young people are the inventors of the future and even in a few years, this story will change again.”

• A History of the World in 100 Objects runs until August 1 in Manarat Al Saadiyat, Saadiyat Island, Abu Dhabi

aseaman@thenational.ae

To celebrate the UAE's 40th National Day, The National collected 40 historial objects which define the UAE. Click here to see videos and photo galleries.