My mother woke up every day wanting to do a hundred things. I can still hear her calling me enthusiastically: "Kako. Kako." My father named me Kakooti, after a mountainous mint leaf used in doogh, the Iranian yoghurt drink. But when my mother went to apply for my passport, she was told that in Armenian, Kakooti was a rude word. So I was renamed Mitra, but everyone still calls me Kakooti.

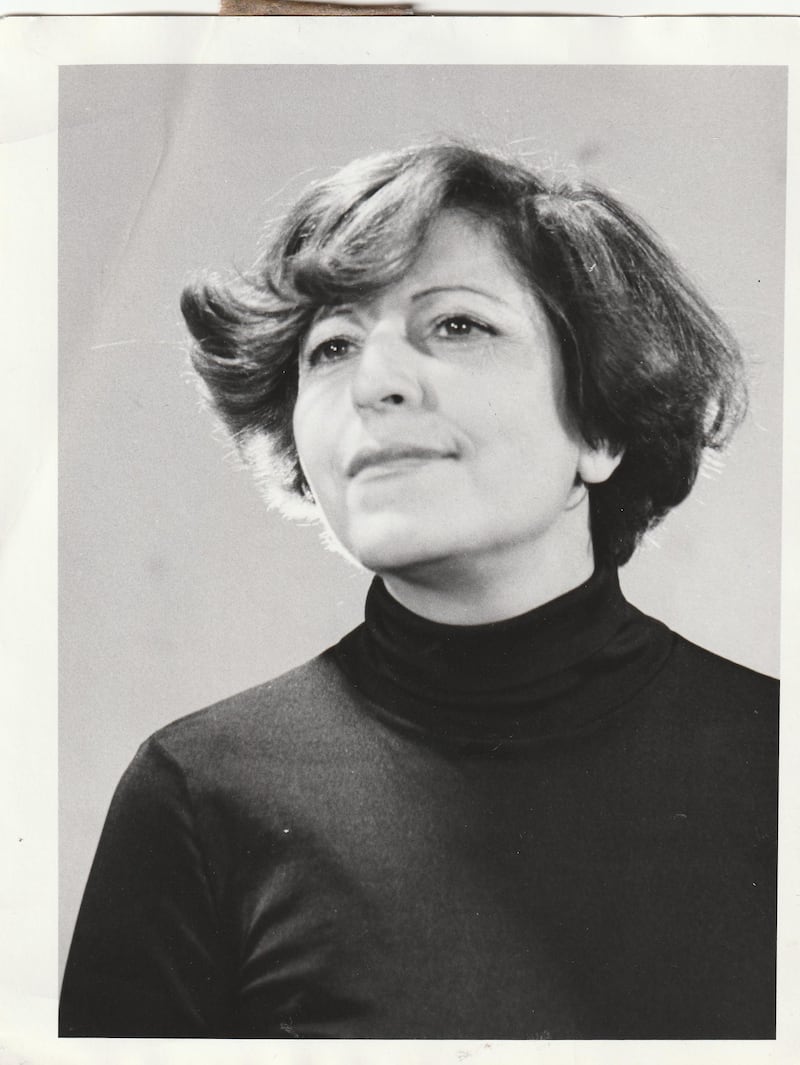

My mother was always happy. She would point out beautiful things, whether it was in nature, paintings or architecture. She taught me how to see the splendour in everything. She was also very determined, and always wanted to be free. She did not believe in religion or politics; she only believed in her art. She fought all her life for her ideas and what is just. I don’t know what kept her going. She had an amazing energy that I do not have.

Between 1948 to 1954 she studied painting at the Faculty of Fine Arts at the University of Tehran, and to earn money, she taught art at a secondary school. She applied for a scholarship in Paris, but found out that someone related to someone important took her place. She was furious and stormed into the grant office. She always argued until she got what she wanted and, a year later, she got a scholarship to study at the Rome Academy.

It was in Italy where she met Iranian poet Forough Farrokhzad, exhibited at the Venice Biennale and graduated from the Academy of Fine Arts in Naples. Some galleries wanted to represent her and once, a “Mr Fellini” wanted to buy her work, but changed his mind when he realised she did not know he was the famous Italian film director Federico Fellini.

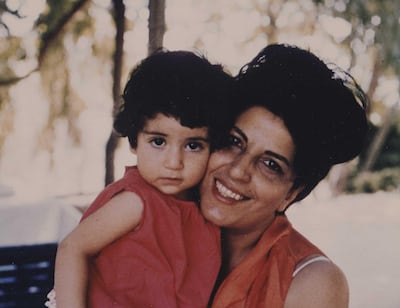

Italy was also where my mother met my father, Iranian composer Morteza Hannaneh. They married in 1958, and a year later, she was offered a professorship at the University of Tehran. French gallerist Denise Rene told my mother not to go back, to stay in Italy where she would be famous. “No thanks,” my mother said, and my parents returned to Iran. I was born in 1964, and a year later, my father left her. She took care of me by herself.

Things were changing quickly in Iran; the country was being modernised. We went to the movies and to her beloved Caspian Sea, where she had a house. It was an open society; we had parties and watched American TV. She wore short skirts, which my grandmother would get mad at her for. Iran was, and still is, so beautiful.

She was very, very tender, and gave me a lot of love, time and support. She was hands-on, especially in my teens. She had a fire in her, always curious, wanting to see more, do more. We did a lot together and travelled a lot, sometimes with her students. It was fun, but also strange to grow up with an artist. I wanted to eat at a table as a family and was jealous of friends who had parents. I did not have the mum who baked cakes and made good things to eat. It was a very bohemian life, with our house always full of artists, actors and poets.

During the day, she taught at the university and at night, she painted. She was an insomniac. When she delved into Kinetic art in 1969, everyone said she was crazy, and she eventually destroyed all of those works because there was no space in our house. I have two pieces left and sold one to Tate Modern in 2018. Many artists in Iran then belonged to the Saqqakhaneh movement, a neo-traditional style rooted in Iranian folk art and culture, but she did not want to be part of anything and did not want her paintings to be labelled only “Iranian”. She did not even like being labelled a female artist. But she was something. To be a woman, a single mother, a teacher, an artist, especially one with radical ideas at the time, was heroic.

I was a student at the French school in Tehran, which closed with the start of the 1979 Revolution. Things started to get strange, so she took me to France in 1980 to enrol me into a boarding school, and then decided to stay with me. A year later, she discovered she had breast cancer, which had spread to her lungs. Everyone said she would not make it and I did not think she would survive. But she wanted to live, and she fought. The doctor said she was bigger and tougher than cancer.

I felt bad for her being in France. To make money, she once had to paint flowers for rich Iranians. The galleries were rude and uninterested in her work. “She’s not young enough, Iran does not interest us, and she is not dead yet,” one said. In Iran, she was known, she had many students, a big house and regular shows. In Paris, she was no one, living in a small, dark apartment and unable to paint because of her health.

I realised then and there that I would never do anything that would mean having to sell my soul. I want people to need me, I want to save people, so I became an ophthalmologist, and she was proud of that. I’m not courageous like her. She started to write and took incredible photographs. French art critic Pierre Restany loved her work and said her memories were in them, that this was technically a projection of exile.

She had a show at the Tehran Museum of Contemporary Art in 2004, and went back and forth to Tehran. She started to feel afraid that she may die in Iran without me, so we started looking for apartments in Paris. She would always tell me that she hoped to die in the sea. She loved the sea and the mountains. In August 2009, six months after we sold her house in Iran, we went to Corsica, which reminded her of the Caspian Sea. She kissed the water and said excitedly: “I love the water.” I saw her head was in the water and just like that, she died.

She always said what she did was important and did not care what people thought. In her last years, I would ask her if she would like her work to be placed in museums. “When I die, it’s all over, I don’t care,” she would say.

It is not over at all. I am determined to preserve her legacy.

More information is at behjat-sadr.com. Remembering the Artist is a monthly series that features artists from the region