My Moroccan friends were anxious. "Are you sure about this?" they asked. "Perhaps better not go," they advised. It was the July of 1993, and I was in Morocco as part of an extended trip across North Africa, where I was doing field research on Arab art and artists. Because I was particularly interested in the work and lives of women artists, I wanted to meet Baya, and that meant I had to fly from Rabat to Algiers, where "the dirty war", as the Algerian Civil War was referred to, was raging. Since March of that year, the war resulted in the assassinations of a string of academics, intellectuals, writers and doctors. Several artists had also fled, but Baya remained in Algeria.

My son Ramzi, who was about 10, was with me and was determined to continue the trip to Algeria as planned, but I left him with a friend in Morocco and arranged to meet them in Tunis. I don’t know why I wasn’t afraid. I guess it’s because I had a purpose.

I learnt of Baya in 1977, when I attended a screening at the University of California Berkeley of a film by Assia Djebar, an Algerian intellectual and feminist, known for her novels and films. "If you like Assia, you must look up Baya," an Algerian student said to me. A few years later, I saw Baya's work at the Jordan National Gallery of Fine Arts in Amman and again in 1992, as part of the show Three Women Painters at the Institut du Monde Arabe in Paris.

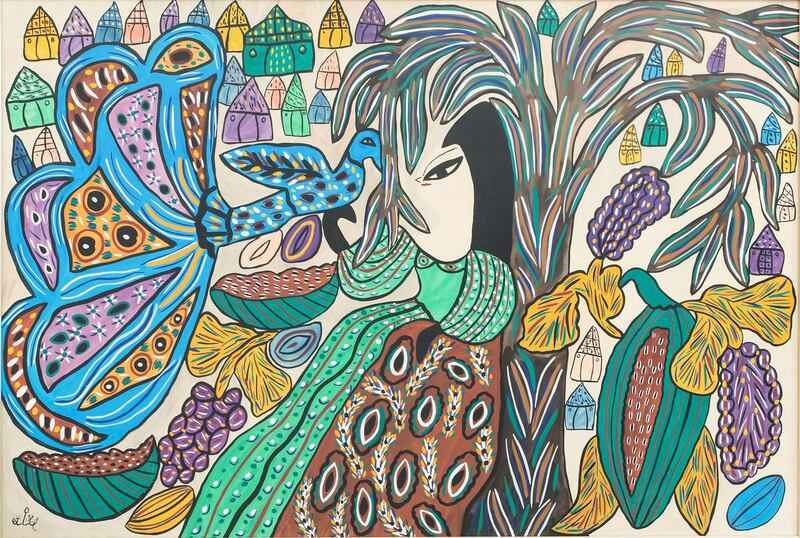

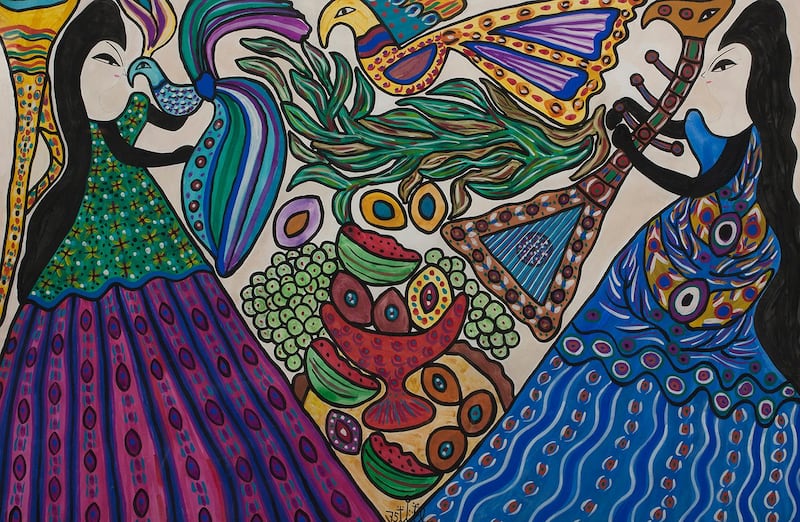

I was intrigued, especially because I was interested in self-taught artists, and Baya was one. I admire her organic style, its utter simplicity on the one hand, and its mysticism and mystery on the other. There is an essence of science fiction to it, as though it comes from another world. She paints such incredible dreamscapes full of stylised shapes of fruits, fish, birds and musical instruments, all of which struck me as highly personal.

The world knew Baya because influential western figures in the art world had paid attention to her. People also love the drama surrounding her life – Baya's parents died when she was five years old and she was raised by her grandmother, with whom she worked at a rose nursery outside Algiers. Baya's talent was noticed by Marguerite Caminat Benhoura, a Frenchwoman married to an Algerian man, who became Baya's guardian and patron of sorts.

Benhoura was well connected in the art world and showed Baya's work to prominent artists, critics and gallerists in France, among them, to famed writer and poet Andre Breton. He included Baya's paintings in the Second Surrealist Exhibition in Paris in July 1947, and in November the same year, Aime Maeght of the Maeght Gallery gave Baya a solo show, for which Breton wrote the catalogue's preface. It was through this show that Picasso saw Baya's paintings and invited her to work for a few months in Vallauris in the South of France, where he lived from 1948 to 1955. By this time, Picasso was interested in art from North Africa and was impressed with the way Baya moulded her clay sculpture.

In 1953, Baya married El Hadj Mahfoud Mahieddine, a well-known musician with whom she had six children and ceased to paint for a decade between 1953 and 1963. I'd heard that Baya was reticent about meeting people, so I arranged to meet with Djebar in Paris to learn more about her. Baya agreed to meet me on the basis that I am an art historian and researcher. I faxed back and forth with Malika Dorbani-Bouabdellah, a writer and curator who headed the conservation department at the National Museum of Fine Arts of Algiers, and who kindly also organised my trip.

It was a warm day when I landed in Algiers. A national curfew was imposed and the streets were lined with checkpoints. My fear kicked in when I opened the window of my room at the St Georges Hotel (now Hotel Djezair) that revealed a wide exposed terrace. My nerves were shot, and my anxiety was mounting. We drove for an hour away from the capital, up a mountain and finally arrived at Baya's home.

I walked into a house with a courtyard in the centre and that instantly had a calming effect on me. It also resembled Baya's paintings. It was as though she dwelt in another world, a microcosm of her paintings. Up here was her own "castle" of sorts, walled by a high fence within which were chirping birds in cages, and Andalusian music heard all throughout, amid the wafting aromas of a tajin she had prepared.

Baya appeared. She was gracious and hospitable, and I instantly felt her to be a very gentle, kind and caring person. We got through introductory chit-chat, and it struck me that though her surroundings were basic, she was highly complex. She slowly started to open up as she served her delicious tajin. We spoke about raising children, and it was clear that family was central to her life.

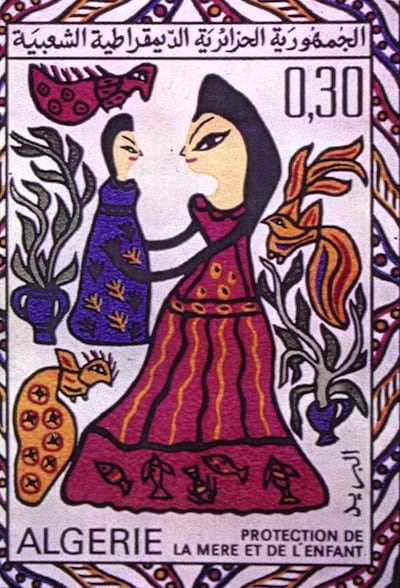

Several times during our conversation, Baya pointed out how proud she was to be highly respected in her home country and that her work was featured on a postage stamp. All the same, I don’t think she cared much about fame. She also spoke enthusiastically about her granddaughter who, like Baya, started painting at an early age.

I wanted to know about Baya's technique and came to learn that she works on the same painting until she finishes it in her "atelier" – a very small space, which was an extension to her kitchen. The woman with the almond eyes in her paintings is not necessarily the same woman; it could be herself, her mother or grandmother. It is many women.

Baya’s paintings involve a lot of repetition with key elements: the women’s wide skirts that are covered with amorphous animal shapes and the musical instruments that are inspired by her husband’s Andalusian musical ensemble, which he often practised in the courtyard.

Though, at first glance, her drawing seem repetitive, a great level of sophistication developed over the years. She struck me as very relaxed about her work and emphatically denied that she was influenced by symbols or patterns of the Kabyle, a Berber ethnic tribe indigenous to northern Algeria.

“What inspires you?” I asked. “My dreams,” she replied. “I wake up each morning

and I remember these figures from my dreams.” In recording her dreams, I got the sense that painting was a form of meditation. Baya’s art is not quintessentially Algerian; it is a reflection of her daily life, and this is how she differs from others who document their locale.

She was happy to know that I had arranged to borrow her work from the Institut du Monde Arabe to show in Forces of Change: Artists in the Arab World, an exhibition that I curated, and which toured five American cities between 1994 and 1995.

I've shared the video of our interview with the Sharjah Art Museum for the currentretrospective on Baya that runs until July 31. I'm delighted that such an important figure in the canon of Arab art is being recognised.

We exchanged warm farewells, and I left feeling rewarded. The next day the road was closed.

Remembering the Artist is a monthly series that features artists from the region