When the Cultural Foundation was first open, from 1981 to 2008, it was the centre for artistic activity in Abu Dhabi. After it closed, many of the works that were shown there were not seen again, and the groups it hosted disbanded. A spell, almost, settled over the building, and no one knew when it would be lifted.

Even now the building evokes a feeling of travelling through time. Less altered than the rest of the Qasr Al Hosn site, the Cultural Foundation opens with an exhibition of its past — Artists and the Cultural Foundation: The Early Years — that extends freely into the present, with contemporary works by historical artists, new commissions, and most excitingly, a glimpse into the variety of work that was made in the 1980s and 1990s, from sculpture to painting to works on paper, many of which have been seen before.

"There is a sense of Abu Dhabi as an outlier," says Maya Allison, who co-curated the show with artist and curator Alia Zaal Lootah. "But this was a place where teenagers went on to become more established artists. What we are looking at here are the seeds that nourished the generation that came later."

A history through art

The show opens with an array of sculptures in the building's grand entrance hall, almost as a scene-setter rather than historical documentation. Cultural Foundation shows were oriented towards painting, and many sculptures wouldn't have made it into public view.

The show stretches across what are now the first-floor galleries, and is divided into two parts: those who exhibited at the Cultural Foundation when it was active, and a second group that the curators refer to as the "Cairo cohort", artists who went abroad to study at the College of Fine Arts in Cairo in the 1980s.

"This was a big surprise to me," says Allison, who previously curated work by the so-called Five — the Dubai and Sharjah-based artists — led by Hassan Sharif, for the show But We Cannot See Them. "I knew they went to London and Paris, but I had not realised how many artists had been sent abroad to Cairo before that."

A pattern in the works

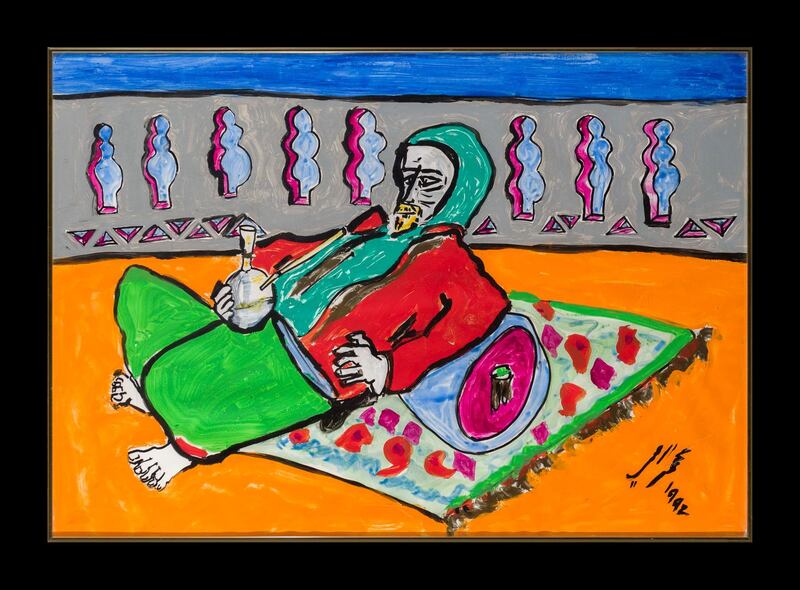

These artists, such as Najat Makki, Mohammed Mandi, Obaid Suroor, Salma Al Marri, and Abdul Rahim Salim, did not collaborate as a group, but Allison and Lootah see some shared traits among them, such as the influence of the sculpture department. Makki, for example, built up bright layers of paint into almost ridged, landscaped works; others incorporate objects they've found into their practice. These artists would have also shown at the Cultural Foundation, which had two major exhibitions a year — the Emirates Fine Arts Exhibition, open to all, and the Spring Exhibition, open to those with either a degree or 10 years' experience in art. There were also smaller shows throughout the year, which artists could book easily to exhibit their work.

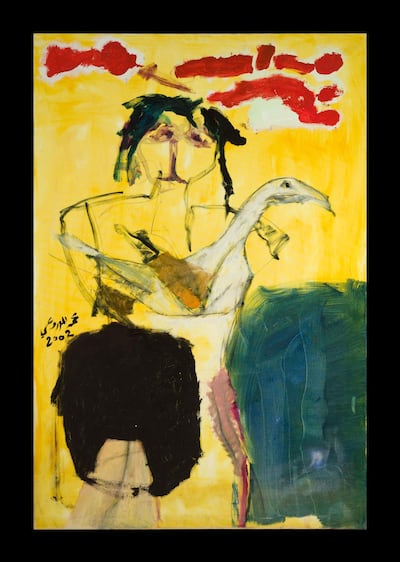

There are some incredible re-introductions, such as the work of Mahmoud Jameel Al Ramahi, whose portraits evoke Egon Schiele, with their gaunt, expressive faces on decorative backgrounds that are as important as the figures themselves. This was literal in one case — The Child (1988) is a picture of a baby, swaddled in yellow cloth and surrounded by decorated handprints. It is a portrait of Al Ramahi's son, who became sick just after he was born, and the handprints are made by family members to protect him (art is power: he survives). In one of the vestibules overlooking the show — former translation booths that have been re-purposed as small viewing areas for works on paper — Allison and Lootah have hung sketches for this painting, showing the other positions for the sleeping child that Al Ramahi played with before deciding on the swaddled baby, lying on his back.

Both in the viewing booth and in the galleries, Al Ramahi's work is beautifully paired with that of his friend Mohamed Al Mazrouei, who worked in the library at the Cultural Foundation. Al Mazrouei is more well-known in Abu Dhabi, but his paintings are nevertheless a revelation — they have a lightness of colour that nearly eclipses their narrative potential, in small vignettes such as a woman who appears to be washing clothes in an untitled 1988 work, with a bird hovering above her and a strange figure below.

The pairing of Al Ramahi and Al Mazrouei also shows the close connection between artists and poets of the time. They were part of the Wall Group and Friends of Art groups, and were associated with the great Emirati poet Ahmed Rashed Thani.

Discoveries under the curators noses

Allison, the director of the NYUAD Art Gallery, and Lootah, a curator at Louvre Abu Dhabi, started with a list of around 20 artists and took off from there, making trips to artists' studios and working their way through archives of the period. Some discoveries were right under their noses — they found a fine, almost Paul Guiragossian-esque painting by Suroor, who studied in Cairo, in the collection of the Department of Culture and Tourism itself. (The Cultural Foundation acquired work from most of its exhibitions, and this collection has now been passed on to DCT.) "Suroor is really underrepresented in the history of UAE art, perhaps because he is based in Ras Al Khaimah," says Allison. "But he has an unbelievably diverse, interesting body of work."

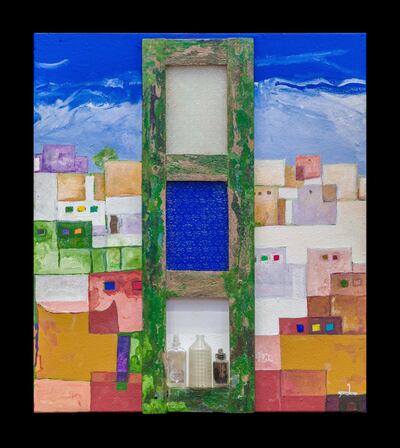

Some of Suroor’s paintings, for example, are executed on teela fabric, the brightly-coloured material that women’s traditional dresses are made of.

"At first we thought he had painted the dots on," says Allison, of a 2015 painting of a fort in Ras Al Khaimah that is peppered with bright blue dots. "But in fact the material itself was spotted, and he only repainted the dots where the fort covered them. The result is a meeting point of old and new."

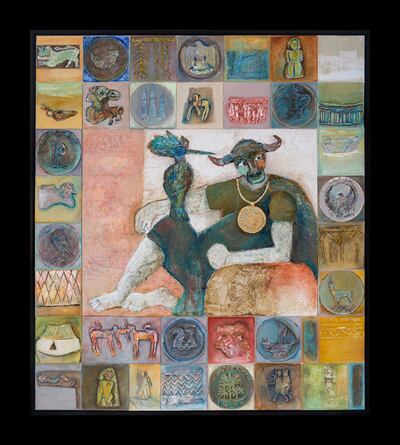

Other paintings of Suroor's are described more accurately as collages, bearing out the influence of Cairo's sculpture department. History and Heritage (2017) includes a window ledge of old bottles that Suroor found while walking in the mountains of the northern emirates.

The Emirati focus

Missing in this show, as a snapshot of the Cultural Foundation as it once was, is the work of other nationalities that would have been shown alongside the work of the Emirati artists.

For Allison, the focus on Emirati artists offered a chance to underline the depth of cultural history in the country. "We felt it was a really important chance for the UAE to be seen as a group with a history, to counter the narrative of culture being imported," she says. "In fact, as elsewhere, the art constantly interacted with multiple artistic streams."

One of these is the influence of the artists who made up the Emirates Fine Arts Society, based in Sharjah.

"We found at least three occasions where EFAS toured their annual group show down to Abu Dhabi, and there might be more," Allison says.

The Early Years includes work by a few of these artists, who tend to be better known than the Abu Dhabi lot, such as a 1988 work by Mohamed Ahmed Ibrahim (incidentally, it is one of his few surviving paintings from that era, as, feeling like a failure, he famously set all his work alight in the mountains in 1999.) His biomorphic, almost primordial forms feel part of a new discussion within the Cultural Foundation context, set among a number of works that parsed the changes from a sand-and-rock landscape to one of rampant building construction.

The exhibition also reveals formal flows of influence among the artists at the time – most notably, the introduction of conceptual art to the region.

Mohammed Al Astad, the son of a fisherman and a member of the Emirates Fine Arts Society, painted accomplished but generic images of landscapes and fishing boats. In 2004, he decided to bury his boat's canvas near the ocean, covering it with bits of metal, so that the elements would create their own painting underground.

"He asked himself, 'Why is Hassan Sharif getting all the attention? So he made his own conceptual art, initially as a joke," says Lootah.

But the results were astounding — earthy displays that are literally imprinted with the changes of time and the natural world of the ocean and sand. "Everyone loved them," Lootah says. "And so he has continued them to this day."

Artists and the Cultural Foundation: The Early Years is free to enter and runs until June 8.

___________________

Read more:

Visualising Palestine: recounting an historic conflict through maps

Middle of what? The tricky business of labelling regional art

Art Bahrain: the people bringing Bahraini art to the world

___________________