For as long as paper has been in existence - the Chinese are usually credited with its invention in the second century - one suspects people have been folding it into shapes for their amusement.

But it was not until the year 1797, with the publication of the Japanese book The Secret of One Thousand Cranes Origami, that formal instructions on creating a figure first appeared in print.

In the two centuries since, the realms of origami have reached new heights, with deft-fingered artists being able to form almost any object, shape or figure that one can imagine.

Yet some are now taking the practice beyond the work of mere hobbyists. Some academic theorists are now utilising complex mathematics and computer technology to test the limits of what conceivably can be manipulated from a sheet of paper.

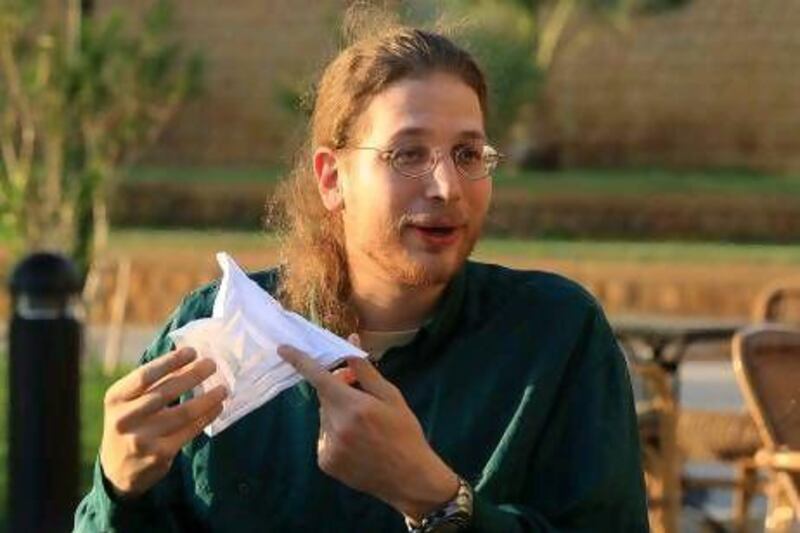

At the forefront of this research is Erik Demaine, a professor in computer science at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) and one of the world's leading experts on theoretical origami.

Demaine recently journeyed to the Middle East to share some of his findings with interested parties at one of the New York University Abu Dhabi Institute's series of lectures.

Much of his research delves into mathematical formulae that is beyond the comprehension of a layman. Yet Demaine is someone who is intent on making his work accessible.

"I want to show people that science can be fun and exciting," he explains in a brief interview shortly before delivering his lecture at the InterContinental Hotel Abu Dhabi.

"I've felt this way about science ever since I was a child. I've always thought of scientific discovery as an adventure," he says.

Demaine's passion for such adventures began at a young age. Born in Halifax, Canada, he was raised by his father, Martin, an expert in glass blowing.

From the age of seven, the pair travelled around the east coast of the US - living in 10 different locations in four years - selling his father's wares. Demaine was home-schooled along the way.

After showing a remarkable gift for computer programming, he persuaded the administrators at Dalhousie University in his hometown to allow him to enrol in a degree course when he was only 12 years old.

A distinguished academic career beckoned and after gaining his doctorate at the age of 20, he was soon appointed as the youngest ever MIT professor.

Now 31, he is a respected authority in computer science.

Yet it is with the relatively new field of computational origami to which he devotes a significant amount of his energies.

"I was starting grad school and was looking for some geometry problems to solve," he says, recounting how this all began.

"Computational origami was really in its infancy as a subject back then. So I came at it from the math side, rather than the origami side."

The possibilities of what can be made from just one piece of paper instantly engaged his natural inquisitiveness.

He says: "I started wondering what shapes can you fold. If I have a big enough square, can I fold any two-dimensional shapes? Can I fold any polygon? Can I fold any two-coloured pattern? Or any three-dimensional surface?

"The answer is yes to all of these questions, as long as [the object] is made out of flat sides.

"So, if you have a large enough piece of paper, in theory you could fold the entire works of Shakespeare. You'd need a piece of paper about as big as the moon though," he smiles.

Another quandary he's delved into is the so-called "single cut" problem.

As Demaine explains, before Harry Houdini found fame as an escapologist, he performed as a regular magician.

One of Houdini's most popular tricks involved folding up a sheet of paper before making one straight cut with scissors to produce an array of shapes.

Demaine has helped prove that any straight-lined shape can be created in this way, from a swan, to a butterfly to, feasibly, the complete alphabet.

While he admits to being primarily a theoretician, devising answers to hypothetical problems like these, some of his ideas have more tangible purposes.

For example, he has often collaborated with his father to create sculptures together.

"I'm from a science field, but my dad comes from a more arty background," he explains. "So origami is a great way for us to meet in the middle and do some collaborative work together."

The pair have attempted folding molten glass into origami shapes, as well as mixing origami models and blown glass into sculptures.

"We decided to do this to show that origami and paper folding is both an art and a science," says Demaine.

"Working with my dad and other artists means I get to do both science and art at the same time. From this, I contend that we're better artists because we study science and better scientists because we study art."

On top of this, there are also some far-reaching applications resulting from his studies.

"As well as making sculptures, we are always looking for practical engineering devices for our designs," says Demaine.

"An example is folding an airbag flat so it can be stored in your steering wheel, so when it deploys it evenly distributes the pressure. We can use it to fold airbags, smaller, but also more safely. So you could say origami can save lives."

Other research has shown that a sheet of paper of a certain area can be transformed into any other shape of the same area. The same is true of 3D objects.

From this, Demaine has devised a programmable matter, which can change its shape and reconfigure into another object.

"This product is only very basic at present, but eventually you could have a cell phone that can change into a laptop when you have more space," he imagines.

"Or a chair that can sit down wherever you are, then you could roll it up into an umbrella. We are also working on building robots that can change into an airplane shape and then into a boat. It's like a real-life version of the Transformers toys.

"It's kind of a tricky concept to grasp, but one that will be possible in a few years."

As Demaine enthuses about his work, he continually plays with a small, square origami model.

"This is actually a model for a space station I've designed," he reveals when I ask what it is.

"What I envisage is that it can be sent into space in a flat sheet, then you put in all these creases and so it would pop into this 3D form by itself.

"So with origami we could make a large object really small for transportation. This would be incredibly important for space travel. You know, you could make it really small and take it out in a space shuttle then deploy it in space."

From a paper bird, to a design for a space station that could one day sustain humans in the ethereal realm. The humble art of paper folding has come a long way.

Hugo Berger is a features writer for The National.