In 1978, Edward Said made orientalism a dirty word. In former times it indicated, in its starchy, school-masterly fashion, a simple academic interest. One could be an orientalist in much the same way as one could be a Greek scholar or a botanist. No longer. "Since the time of Homer," wrote Said, "every European, in what he could say about the Orient, was a racist, an imperialist, and almost totally ethnocentric." The Arab world was, he argued, a shadow theatre into which the European projected his fears and desires, a fantastic realm of deserts, despots and dusky seraglio maids. Such remarks shaped the agenda for subsequent debate over the West's ideas about the East. They also - ironically, inevitably - created an appetite for a lot of creaky Victorian writing and painting that, without Said's polemics, might have fallen out of fashion, straight through kitsch and into obscurity.

As if admiring lithograph odalisques weren't its own reward, cultural conservatives now got the added pleasure of getting up the noses of colonial studies PhDs, who could in turn revenge themselves by issuing burn notices on such cherished targets as Jane Austen. That, in a nutshell, is why the rights and wrongs of orientalism have been one of the growth fields in western humanities faculties for the past three decades.

There were skirmishes along these partisan lines when the reviews for the Tate's Lure of the East show came out in Britain last year. This editorialising survey of two centuries of British orientalist painting struck a "relentless tone of self-pity, aggrievement and victimhood" according to the Daily Telegraph's Richard Dorment. Those responsible "haven't noticed that, if anything, British artists tended to idealise the Arab world at the expense of the European". On the contrary, argued the Observer's Laura Cumming, many of the pictures are deservedly controversial and the wall text was "good and apt".

"It's a show to read as much as to view," she warned. And now it's a show to translate. The Tate has taken Britain's uneasy conscience on tour, first to Turkey and now, as of today, to the Sharjah Art Museum. In the process, the pat polarity of East and West has been complicated in interesting ways - not least by emphasising the point that art-buyers in the Muslim world seem to like some of the stuff.

"Sharjah has had a long legacy of collecting orientalist works," says Manal Ataya, the director general of the Sharjah Museums Department. "We have a collection of over 200 lithographs and paintings of David Roberts that we've collected, as well as a comprehensive collection of orientalist works in watercolours and oils, two of which are now part of the exhibition with the Tate." Indeed, she tells me, part of the museum's motivation for bringing the show to Sharjah was the "great opportunity to share what we have". As she explains, Roberts, the 19th-century Scottish scenery painter best known for his grand views of Egypt and the eastern Mediterranean, is a natural object of curiosity for eastern collectors. His detailed and apparently faithful studies of places which time has since transformed offer a window onto a vanished past. "Besides being historically relevant, many of these works are historically accurate," says Ataya.

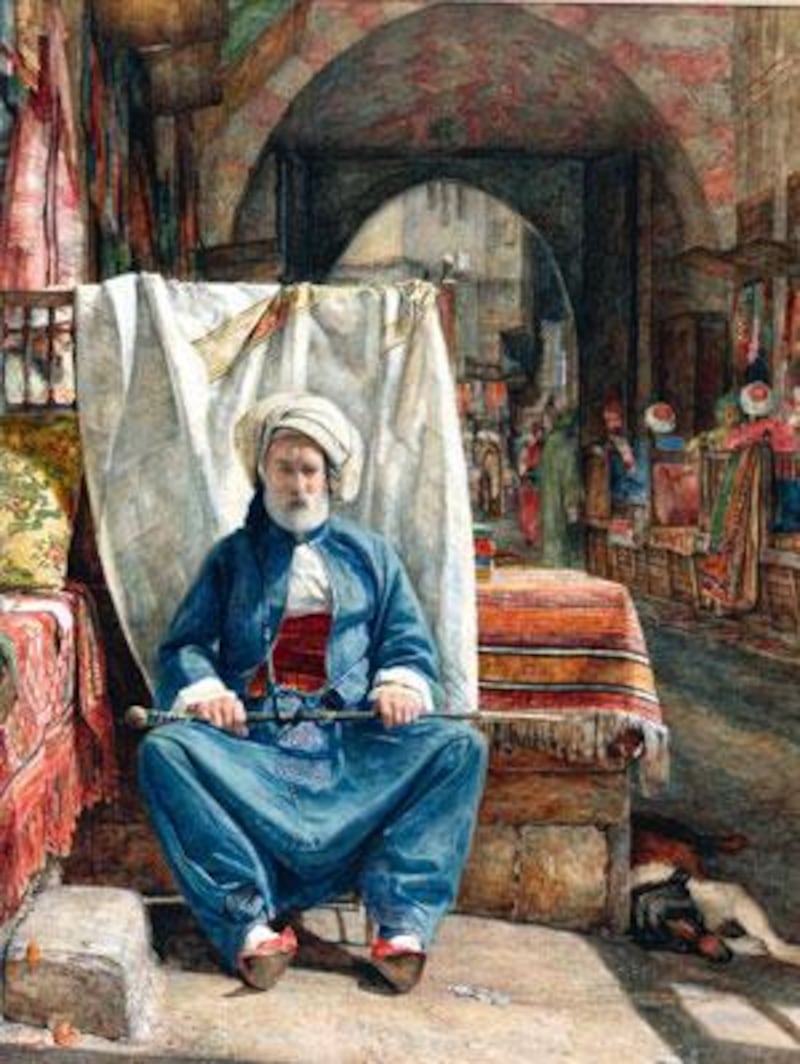

This points to a peculiar characteristic of British orientalism, as contrasted with the florid excesses of its French cousin. There were exceptional specimens, of course: the madman Richard Dadd, for example, who spent most of his career in Bedlam after murdering his father. He became unhinged during a youthful trip down the Nile and thereafter painted his obsessively detailed Arabian scenes from memory, or else conjured them from the same well of glassy-eyed fantasy as supplied his strange, nauseous fairy paintings. Yet on the whole, the British style appeared, at least by comparison with the French, sober and documentary. As the 19th century opened up the world by rail, steamboat and Thomas Cook, British artists flooded into the eastern Mediterranean. Some - Roberts, for example - rattled around the famous sights in tearing haste, storing up sketches and images of exotic scenes that they could elaborate in the comfort of their British studios for the remainder of their careers. Others took their time: the neglected Scottish painter Arthur Melville, for example, spent two and a half years venturing around the Gulf and deep into present-day Pakistan. Yet they were united by the techniques and preoccupations they brought with them as British artists.

Among other things, this meant a preference for detailed landscapes and everyday domestic scenes over the flamboyant Romantic history painting of the French. They may not have been altogether free of the disorders so emphatically diagnosed by Edward Said, but the elements of prurience and wishfulness in their work at least came tempered by a good deal of close observation. "Hence," explains the Tate curator Christine Riding, "you do not get in British art a Death of Sardanapalus" - Eugene Delacroix's torrid depiction of the fabled sybarites' last moments. Quite apart from anything else, there wasn't the market for that kind of stuff in Britain. Rather, we get work in transplanted, rather homely British idioms: take John Frederick Lewis, and his Courtyard of the Coptic Patriarch's House in Cairo, a domestic scene teeming with plausible detail - ducks splashing in the fountain pool, a girl sitting on a blanket and slicing a melon. The habits of the RA die hard. "The British thought they were better than the French at painting the East," Riding says. "They thought they were more honest. They thought they had a better understanding of the culture. They thought they were less dismissive. So there's that inevitable national rivalry... it's not just about the West and the East. It's about the West and the West." Intriguingly, the show's trip to Istanbul last year suggested ways in which it's about the East and the East, too. "In Istanbul, and certainly with the Pera Museum," says Riding, "there is a tremendous amount of nostalgia about the Ottoman Empire. I think they really are revisiting that whole period of history... really looking at themselves as orientalists of an empire." As a chronicler of that history, John Frederick Lewis, who spent almost a decade living in the Ottoman trading hub of Cairo, exercises a peculiar allure over a Turkish population eager to enter into the romance of their own imperial hinterland.

Joseph Farquharson's 1888 oilwork The Hour of Prayer: Interior of the Mosque of Sultan Hasan, Cairo. Courtesy of Aberdeen Art Gallery & Museum Collection.

As Riding explains, "they see him as really representing a kind of jewel-like past. And I'm sure that if the Pera museum - well, they do buy western works of art - but I think they would acquire John Frederick Lewis if they could, because I think they seem as very much part of that cultural development." The show was a big hit in Istanbul - often, says Riding, attracting more than 1,000 visitors a day. Ottoman orientalism appears to have a feel-good factor lacking to its European counterparts, at least in the West. It will be interesting, then, to see how the exhibition is received in the UAE, a region without the incentive of specifically local boosterism to make allowances for the stuff. Many of the paintings are extremely lovely, with the little-known Lewis representing a particular find. William Holman Hunt and Richard Dadd were great talents and dramatic personalities who cast long shadows even now, but other names are very minor: indifferent sloggers such as Joseph Farquharson, "the painting Laird" as he was called, or Thomas Seddon. Of the latter, William Ruskin wrote, a little backhandedly it may seem, that he had produced "the first landscapes uniting perfect artistic skill with topographical accuracy; being directed, with stern self-restraint, to no other purpose than that of giving to persons who cannot travel trustworthy knowledge of the scenes which ought to be most interesting to them." You can see some of that same stern self-restraint at the exhibition. Thus the faults of the British orientalists - their prosiness as much as their excesses of poetry - are on display alongside their virtues. Or perhaps, to take the alternative view, their stolidity and restraint were the very virtues that preserved them, at least some of the time, from the sins of the French. These are deep questions, not easily resolved. All the same, there's an excellent forum in which to broach them. On March 7, the British Council is staging Cultural Question Time, a public debate modelled on the BBC radio programme which shares most of its name. Andrea Rose, the director of visual arts at the British Council, will chair the event, taking questions from the audience and marshalling the panelists, who include the Palestinian singer Reem Kelani and the Bidoun editor Antonia Carver. Head along to the Sharjah Art Museum for 7pm and add your own voice to the chorus - discordant, though usually not without one or two unexpected harmonies - which rises up wherever the topic of orientalism is discussed. You might even discover a painter or two that you like. elake@thenational.ae Lure of the East opens today at 7pm, Sharjah Art Museum (sharjahmuseums.ae). Until April 30.