A rapturous sweep of human history in 250 objects currently at Manarat Al Saadiyat in Abu Dhabi, Treasure's of the World's Cultures is a partnership between the British Museum and Abu Dhabi Tourism and Culture Authority. The exhibition features objects from across the globe and from prehistory to today. Here, we provide an in-depth look at three objects that caught our attention:

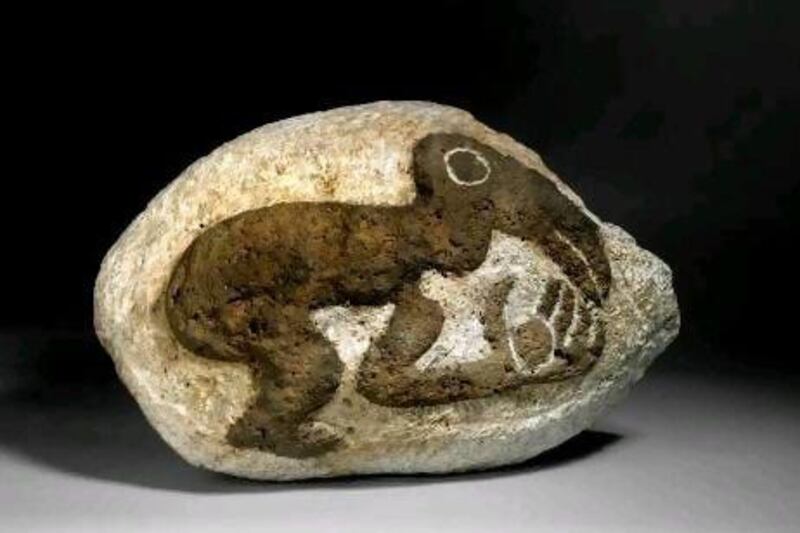

Birdman Boulder from Rapanui, Easter Island

Think Easter Island; think rows of head statues looking out to the South Pacific. These ominous visages were carved and erected by the Rapa Nui, a Polynesian people some scholars reckon settled on this once lush island as recently as 700-800 AD.

Today, Easter Island is largely barren - an example of radical deforestation and consequent societal collapse.

There are conflicting theories of how this happened. But this exquisitely carved boulder, depicting a half-man, half-bird creature, is testament to the dreams of Rapa Nui society as it fell into crisis.

Some archaeologists believe that Easter Island was once a thicket of fruit-bearing trees and awash with tasty wildlife. These giant carved heads were tributes to the spirits of the tribe's ancient ancestors, but demanded leverage to move them around and the Rapa Nui began chopping down trees en-masse.

The more they chopped, the scarcer resources became. As crops failed in poor soil, the villagers appealed to their ancestors for help by - you guessed it - raising more stone heads.

In the turmoil, a new belief started to develop: the birdman cult. Every year, the villagers would race to the top of a cliff to see who could retrieve the eggs of the sooty tern seabird first and be crowned master of the island's dwindling resources.

This boulder depicts the birdman. In this hybrid myth, we sense the tribe's yearning to fly away. They created a god that, unlike them, could escape the island.

As we deplete the world's resources and build monuments to our own power, this interpretation of the fate of early Rapa Nui society has a chilling significance.

Gold fish from the Oxus Treasure Takht-i Kuwad, Tajikistan

The glint of its gold body makes the fish seem pleasantly slimy. Looking down at its hammered and intricately decorated body, there's a feeling that it might slide from our hands if grasped too lightly. It seems imbued with vitality and not a mere ornament; its likely use as a means to carry liquids only emphasises this life-giving look.

But the best part of this stunning little fish is the long journey it has taken to get to Abu Dhabi. The piece is a rare and wonderful example of gold-working from the Achaemenid Empire, the furthest eastern spread of ancient Persian civilisation.

On the Oxus River, in modern day Tajikistan, this fish formed part of one of the world's greatest treasure troves, more than 170 objects carved by the Achaemenids around the fifth century BC.

The British Museum has it that in the 1880s, Captain FC Burton, a British political officer in Afghanistan, helped merchants escape from bandits who had hijacked their caravan on the road to Peshawar. They were carrying pieces recovered from the Oxus Treasure - gold scabbards, finger rings, a gilded model of a chariot. Captain Burton is said to have bought a gold armlet from them, which ended up in London's Victoria & Albert Museum, while other pieces from the treasure were later acquired for the museum from the bazaars of Rawalpindi, close to Islamabad.

Many of the great acquisitions of Europe's museums have a back story of colonial-era plunder, but the alleged tale of the Oxus Treasure is a little more chivalrous.

Head of a goddess, probably Aphrodite. Satala, Turkey

We have to imagine the way her eyes would have glittered because the precious stones have long since been snaffled. But there's life in the old girl yet - see how the sculpting of the mouth seems to quiver if we stare long enough? Exploring the totality of the face can reveal a whole raft of different emotions.

This head fragment was once part of a whole statue - probably Aphrodite, the Greek goddess of love - but was recovered with only a well-worn arm in a farmer's field in the north-east of Turkey in 1877.

It is a fine example of just how far Greek aesthetics and Hellenistic culture as a whole spread throughout the ancient world. The British Museum believes that this may date from the Armenian Empire of Tigranes The Great, whose society prospered as he pushed the boundaries of the kingdom further.

Yet this bronze head really is a treasure because looking at it connects us with its own time. When we stare into those empty eye sockets, we don't feel so distant as we do looking at, for instance, the carvings of the Ancient Egyptian. Instead, there's some kinship, mutual understanding and feeling funnelling out through the annals of history. Aphrodite might be only a face but she's still got it, 2,000 years later.

Treasures of the World's Cultures continues at Manarat Al Saadiyat on Saadiyat Island in Abu Dhabi until July 17. The exhibit is open daily, from 10am to 8pm. Entrance is free