The Rohingya crisis may be damaging Myanmar's international standing, but in Yangon life goes on. There's an expectant atmosphere on the grounds of the colonial-era Secretariat complex in the city's downtown district. Wide-eyed young people have come armed with smiles and smartphones. More forward-thinking visitors have arrived with professional photographers in tow. In the grounds outside the horseshoe-shaped, 15,200-square-metre building, construction workers and engineers are collecting steel and carrying around armloads of maps.

The 120-year-old, red-brick Secretariat – also known as the Ministers' Building – holds a unique place in the history of Myanmar. As the seat of British rule, it was the chief symbol of occupation. Later, it was the site of Burma's first independent parliament. In 1947, General Aung San, the founder of Burmese independence and father of Aung San Suu Kyi, was assassinated there with several cabinet members by paramilitaries loyal to a former prime minister.

Under military rule from 1962, the complex was closed to the public, and on city streets it established a reputation as a place of intrigue – until several years ago anyone attempting to photograph it could expect to attract the attention of security guards. All the while, the Secretariat has been regarded as an architectural treasure, "perhaps the most significant secular heritage site in Myanmar", according to the Yangon Heritage Trust, an NGO.

The complex has survived earthquakes, Japanese air raids during the Second World War, and Cyclone Nargis, which killed around 140,000 people in 2008. Last year, more than 40,000 people crammed inside when the authorities opened the complex to the public to mark the 70th anniversary of Aung San's death.

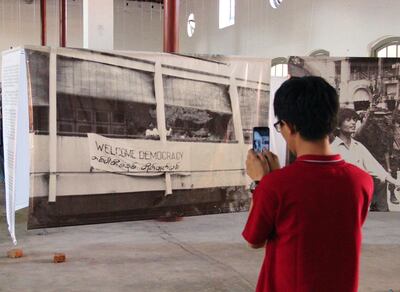

Now, as Myanmar opens up to the world, the Secretariat is opening up to Myanmar. A year ago, authorities agreed for the first time to temporarily open its southern wing for an exhibition that attracted more than 50,000 visitors. Since December, public tours of the complex have been permitted. For the young and glamorous now wandering its halls and stately rooms – experiencing the inside of a building off limits to the generations that came before them – the sense of past and present colliding is almost palpable.

That's because the Secretariat is now the scene of one of the largest restorations in the world. A reported $100 million (Dh367 million) is being poured into a renovation effort to return its damaged turrets, creaking staircases and crumbling stuccos to their former glory. In 2012, the military government awarded a 50-year lease to the Anawmar Art Group, whose board includes artists and influential families with interests in the arts. The Yangon Heritage Trust plays a consultancy role, while work on the building's most delicate internal and exterior features is overseen by Italian firm, Architetti Croce.

“Restoring this grand, colonial building to its former glory and reinvigorating its internal spaces with a programme of arts-related functions, seeks to both preserve Yangon’s cultural past, and cultivate Myanmar’s creative future,” Jason Pomeroy, head of the Singapore-headquartered Pomeroy Studio that is overseeing the restoration process, said in December. Finance is thought to be provided by the state and private investors, although how much and from where cuts to one of the project’s less transparent aspects.

Given its prominent history, it’s no surprise that a debate is emerging over how the restored Secretariat can best reflect Myanmar’s history and future ambition. A section of the complex is expected to house retail spaces and offices (as well as a museum and galleries), and some have expressed concern that given its history reflects Myanmar’s broader 20th century experience, whether it is the right place for a high-end shopping mall.

“We wanted to show this building should be used for culture, which is its most obvious and reasonable use,” says Franz Xaver Augustin, director of the Goethe Institute in Myanmar. As the driving force behind the exhibitions held at the Secretariat in 2017 and this year, Augustin says he first had to overcome numerous logistical difficulties. He suggests the southern wing be used as a permanent exhibition space but feels it’s the place of the government to step in and take charge.

There was controversy three years ago when an Anawmar board member was accused of holding a lavish private birthday party on the Secretariat's grounds. Thi Thi Tun, the alleged transgressor, denied a party took place, saying that instead, a group of potential donors had been invited to tour the site.

In a country undergoing unprecedented change, the Secretariat’s ambiguous future touches upon a broader debate about how to protect Yangon, and indeed Myanmar’s, architectural heritage. Across Yangon, luxury hotels and residencies are being built a great speed. Construction crews work around the clock on land and buildings once occupied by a host of decrepit state enterprises.

Two blocks north of the Secretariat complex, a $2.5bn (Dh9.2bn) project to transform Yangon’s main railway station is under way. There, questions around how and when an estimated 10,000 railway employees and their families will be rehomed are still under review. Over decades, a self-contained community serviced with shops and restaurants developed, and although railway authorities have outlined a plan to move staff and their families to areas on the city’s outskirts, uncertainty reigns around if and how the community fabric can be maintained.

_____________________

Read more:

All mapped out in the Myeik Archipelago in southern Myanmar

Hotel Insider: Belmond Governor’s Residence, Yangon

_____________________

And while a resurgent café and restaurant culture, fuelled by a new cohort of young people flush with disposable income, has seen dozens of buildings preserved in their original state, a broader state-wide programme has yet to be adopted or proposed. But it’s the status of the Secretariat building, a space that spans the sensitive divide between Myanmar’s history of occupation and independence, that occupies a higher level of scrutiny; it even merited a visit by US president Barack Obama in November 2014.

“You can find a balance (between conservation and profit-making),” says Augustin, a self-confessed culture aficionado. “I am astonished that there is obviously no clear vision of the government of Myanmar and of Yangon for the future public use of this unique historic monument in the heart of the city.”