A petition to prevent the auction of works by two pioneering Moroccan artists has sparked a debate about the safeguarding of cultural heritage from the kingdom’s expanding art market.

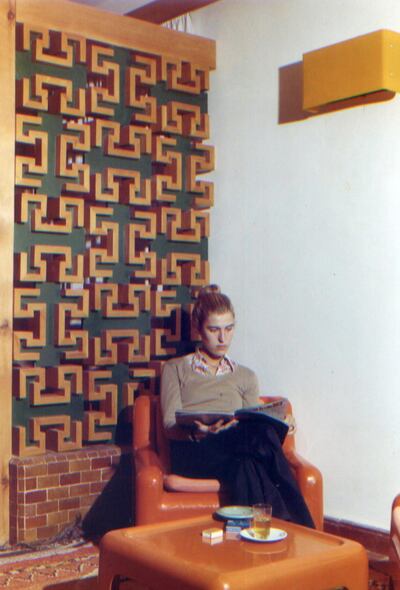

Two painted ceiling panels, two carved wood compositions and a series of lithographies by Mohammed Melehi, and 14 carved wood claustral and mousharabiyas by Mohammed Chabaa, will be sold in Morocco by French auction house Artcurial on Sunday, May 30. The works range from 500 to 80,000 euros ($600 - $97,649).

But the artists’ heirs have said the sale would damage the integrity of the artworks. The items were originally designed in collaboration with architects Fabrice de Mazieres and Abdeslem Faraoui, for the Roses du Dades hotel in southern Morocco.

“The works were intended as integrations, not standalone artworks,” said Nadia Chabaa, the artist’s daughter who co-launched the petition.

“The artists and architects worked together from the outset of the building design. Their collaboration has an enormous cultural heritage value.”

In the 1970s, the two architects were commissioned by Morocco’s national tourism office to develop three hotels in the arid southern plains of the country. The ensuing brutalist structures were inspired by the local terrain and buildings of the indigenous Berber community.

For the interiors, they collaborated with leading Moroccan artists of the time.

“My father often went to visit the building while it was in construction” said Chabaa, recalling her visit to the construction site with her father, as a child. “He told me how they discussed the building’s spatial configuration.”

“It was a unique experience for my father. He believed it would revive the traditional relationship between the master, or muallem, and his artisans,” she added, citing Islamic building traditions.

Leading heritage experts, including those appointed by Morocco’s Ministry of Culture, consider these buildings and their artworks as important examples of Morocco’s modern heritage.

“It was among the first collaborations in the Arab world to marry modern architecture with artistic expression,” said Mehdi Qotbi, the president of Morocco’s National Foundation for Museums, a public body.

Yet decades later, all three buildings have yet to be listed in Morocco's cultural heritage list. Some sustained changes to their interiors after they were sold to private owners, and others damaged from decades of neglect.

The owners of the Rose du Dades hotel declined to comment on the sale after being contacted by The National. But so long as the building and the artworks aren't listed, it is within their legal right to sell the works.

Campaigners say the artists’ heirs should have been consulted.

“Art is subject to the artist’s moral rights, and cannot be treated like other commodities,” said Salma Lahlou, an independent curator and signatory to the petition.

Elias Khrouz, a lawyer specialising in copyright law, who is based in Casablanca, said the artists’ children had legal grounds on which to oppose the sale, but the existing campaign is not enough to prevent it.

“They would need to present a case to the Moroccan courts,” he added.

Others believe that direct government intervention is required before the sale takes place. On April 13, Minister of Culture Othman Al Ferdaouss announced on Twitter that the Ministry was reviewing some of Melehi and Chabaa’s work for a prospective listing.

On May 12, Mamma Group, a Moroccan organisation focused on the protection of 20th century heritage, filed a request for the three hotels to be considered on Morocco’s heritage list.

“This gives the Ministry all the powers to stop the sale temporarily while they study the building for classification,” said Imad Dehmani, the organisation’s director.

In an open letter, the architect’s widow Pauline de Mazieres (who did not sign the petition) said she hoped the artworks would be “acquired by the state and protected in a national museum.”

But this week, Qotbi told The National that the National Foundation for Museums did not have the required funds to purchase the artworks. He pointed to a new regulation issued in May that gave the foundation the pre-emptive right to purchase artworks, which could prevent similar issues from arising in the future.

And, as Morocco seeks to expand its local art market, the debate puts a spotlight on auction houses, whose role as brokers often blurs the line of accountability.

Artcurial’s branch in Morocco, which is organising the sale, said it was acting within its remit.

“We have been appointed by the owners of the hotel Rose du Dades to sell the works of Chabaa and Melehi […] we have been in touch with the Ministry of Culture,” they said in a statement.

The auction house’s headquarters in Paris did not respond for comment.

“It’s a battle between the art market and cultural institutions,” said Lahlou.