In his latest and most ambitious artwork to date, the Beirut-born, Berlin-based artist Mohamad-Said Baalbaki delves into an archaeological and theological enigma. On the eve of the First World War, a German archaeologist named Werner von Königswald was working on an excavation site in Jerusalem when he located the remains of an Islamic burial ground on the south-eastern slope of the Temple Mount. Near one of the site's retaining walls, he found a small niche with a case of bone fragments tucked inside.

For von Königswald, the discovery was both fascinating and frustrating. He knew the bones were those of an animal, but he had no idea what kind. Out of his academic depth, he sent the bones to a colleague, a palaeontologist in Berlin named Hans Wellenhofer. Von Königswald asked Wellenhofer to make copies of the bones and to send them, in turn, to an ornithologist in Munich named Heinrich Ralph Glücksvogel.

Wellenhofer and Glücksvogel struck up a lively correspondence, in which they debated their theories about the bones. Wellenhofer, empirical and to the point, argued that they were the remains of a horse with malformations on its back. In support, he found photographs and engravings of similarly disfigured beasts with limb-like protrusions jutting from their shoulders.

Glücksvogel, however, saw the skeletal stumps differently. Birds being his area of expertise, he thought they were wings, and further, that the bones lent evidence to the existence of a creature akin to the Pegasus of classical mythology. To make his case, Glücksvogel pointed to the wealth of art-historical references to winged figures from various cultures and civilisations all over the world, as well as to the particular context of von Königswald's discovery.

In Arabic, Pegasus is known as Al Buraq, although the two figures do not match up exactly. In Greek mythology, Pegasus is a white horse with majestic wings, sired by Poseidon and born from the severing of Medusa's head. Al Buraq, however, is depicted as a winged horse with a human head (the word itself translates from Arabic as lightning). According to Islamic tradition, the Prophet Mohammed made a physical and spiritual journey from Mecca to Jerusalem and back again over the course of a single night in the seventh century. The angel Gabriel appeared at the Kaaba and gave the Prophet a winged steed, Al Buraq, to spirit him on his travels. In Jerusalem, the Prophet stepped down and tied Al Buraq to a wall near Al Aqsa Mosque. For this reason, the Western Wall is known as the Wall of Buraq in Islam, just as the Temple Mount is known as Al Haram al Sharif, or Noble Sanctuary.

The Night Journey (Al Isra) is one of the most critical chapters, or suwar, in the Quran, detailing the obligations of daily prayer, as well as prohibitions on blasphemy and adultery. Al Isra and the second part of the journey, Al Miraj, when the Prophet ascends through the heavens before returning home, have proven fertile subjects for artists in the region, such as the Iraqi modernist Shakr Hassan al Said, who depicted the journey by burning holes in his paintings. But in the Quranic text itself, the story is as spare as it is vague, referring only to the Prophet being carried by night from the Sacred Mosque to the Farthest Mosque. The details about the winged steed and the wall come from the supplemental narratives of the hadith and accounts of the Prophet's father-in-law, Abu Bakr.

However tenuous, Glücksvogel's conclusion about the bones would have had profound theological resonance, and would have given greater weight to the elements of the Night Journey absent from the Quranic text. But the debate between Wellenhofer and Glücksvogel came to an untimely end. The Museum of Natural History, where Wellenhofer worked, was bombed during the Second World War, and the bones were destroyed. Around the same time, Glücksvogel passed away. By the mid-20th century, their competing theories of the malformed or mythological beast had been completely forgotten.

Baalbaki's work, entitled Al Buraq I: The Prophet's Human-Headed Mount, is a sprawling, intricately detailed installation that ostensibly retrieves the work of Wellenhofer and Glücksvogel from obscurity. Conceived as the first in a trilogy of works on Al Buraq, the installation is on view at the gallery Maqam in Beirut until the end of January. Baalbaki just finished the second instalment in the trilogy, entitled Al Buraq II: Chimerical Kingdoms, which will be exhibited later this year at the Georg-Kolbe Museum in Berlin, and he is getting ready to start work on the third, entitled Al Buraq III: The Exhibition that Never Took Place, which brings the story of the professors and the creature they studied to an end.

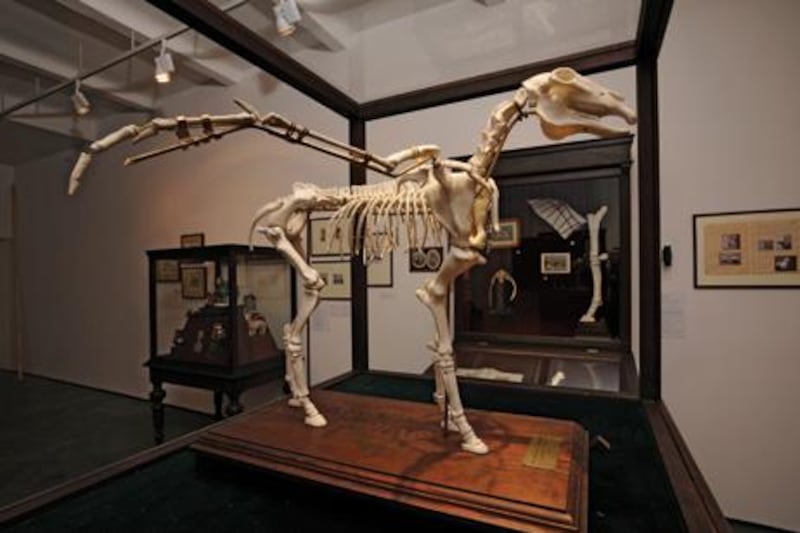

For part one of Baalbaki's work, the letters exchanged between Wellenhofer and Glücksvogel are framed and hung on the wall alongside photographs of von Königswald's archeological dig, anatomical sketches and engravings of medical oddities. Portraits of the professors and their families and late Ottoman-era sultans are seen next to a gilded shoulder blade and several glass-fronted display cases filled with miniature paintings and diminutive figurines, all variations on the winged creatures of global mythology. The exhibition's centrepiece is a scaled down replica of the original bone fragments, arranged like Pegasus with a set of wide and mighty wings.

The catch is that every detail of the story, from the bones to the professors and their findings, is a figment of Baalbaki's imagination. Every object in the show, down to the frames and display cases, was likewise crafted in his Berlin studio. Only the photographs were found. The names offer the first hint of a hoax - Glücksvogel, for example, translates from German as "lucky bird." From there, Baalbaki readily admits that he drew the characters from his dreams and built an elaborate fiction around them.

As such, the first instalment in the Al Buraq trilogy plays in the spaces between fact and fiction, authenticity and forgery. Baalbaki's work challenges the divisions between knowledge and interpretation, the approach of natural sciences versus that of cultural studies and, in the current political climate, the faltering credibility of images and curatorial displays.

Without reading the explanatory wall text, one could easily walk in and out of Baalbaki's exhibition thinking that the story is real. But knowing that it is not means grappling with the artist's formal and conceptual choices. Why mount an exhibition in 2010 that looks like a 19th-century cabinet of curiosities? Why evoke the atmosphere of a museum in a city that is famously lacking all such institutions, except an austerely depoliticised national museum of primarily Greco-Roman artefacts? What is the significance of the early 20th-century colonial era in which Baalbaki's story is set? What are the consequences of contemporary art probing sensitive areas of religious exegesis?

One of the most striking things about Al-Buraq is that, until now, Baalbaki has been known primarily as a painter. His last exhibition in Beirut - staged a year ago in the derelict, dome-shaped cinema on the edge of Martyrs' Square - featured a series of more than 40 canvases that tied Baalbaki's childhood memories of Lebanon's civil war to an excerpt from TS Eliot's The Waste Land, starting with "A heap of broken images", and ending with "I will show you fear in a handful of dust." Those paintings were technically accomplished, and commercially viable - one of them sold at a Christie's auction this past autumn for just under $30,000. But nothing in them even hinted at the conceptual daring of Baalbaki's new work.

"As I child, I was always interested in natural sciences," he says, "and I always had a thirst for history." When archaeologists in Beirut began excavating the city centre in the 1990s, after the end of the civil war, "I used to go there every day to watch and see what was discovered. But I was born into a family of painters."

Baalbaki's father, his younger brother Ayman and his cousin Oussama are all well-regarded painters in Lebanon. Like them, Baalbaki studied at the Lebanese University's Institute of Fine Arts. Then he performed a period of mandatory military service, after which he travelled to Amman to study with the renowned Syrian-German painter Marwan Kassab Bachi. "It was through Marwan that I ended up in Berlin," he says of the city he moved to in 2002. "I basically followed him there."

In Berlin, Baalbacki began, paradoxically, to make paintings about Beirut and his experience of the civil war. He was back in Lebanon, preparing for an exhibition of those works, when the war of 2006 began. "That was detrimental," he says. "I was painting my memories of an old war when a new war arrived." Since then, his practice has taken a conceptual turn. Baalbaki's new work is less about composition, textures and brush strokes, and more about archives, museum studies and media representations of political conflict in the Middle East.

In conversation, Baalbaki traces an interesting lineage from the ongoing wars in Iraq and Afghanistan, Colin Powell's United Nations testimony about Saddam Hussein's chemical weapons programme, and the 24-hour television news coverage of the first Gulf War, back to the image of politicians drawing thick, seemingly arbitrary lines on maps of the region at the time of Sykes-Picot. In the artist's view, all of these episodes involve images that turn out to be untrustworthy.

Baalbaki is searing in his criticism of the period between the two world wars, when his trilogy is set. "The colonial powers offered us chimerical kingdoms, countries that were fake, that didn't exist. The history is haphazard," he says. "How the borders were drawn - geographic, political and ethnic borders - nurtured many conflicts in the region. It's a world that is unstable." As with the bones of a quizzical, fictional beast, Baalbaki urges viewers to debate whether the remains of that world are a matter of malformation or myth.

Kaelen Wilson-Goldie reports for The National from Beirut.