In a memorable image from the photographer Hugo Tillman's show at Dubai's Elementa Gallery, the popular Chinese contemporary artist Zhou Tiehai floats along the Huangpu River in Shanghai in a urinal labelled the SS Duchamp. Behind him is the iconic skyline of his city, complete with the Bund waterfront promenade and the colonial-style Peace Hotel poking its green roof out of the background. Is it a statement about art's ability to save the artist? Or is it merely a funny Duchampian message from Zhou's unconscious? Probably it's both.

For Tillman's show, Film Stills of the Mind, the artist spent two years interviewing 80 Chinese artists about their hopes, dreams, fears and memories. After these long sit-downs, Tillman chanelled these discussions into vivid images, constructing sets in his studio that reflected the realms of the subconscious. By doing this, Tillman gives his peers a chance to turn their imagined reveries into reality or to relive recollections of the past. The audience goes along with Tillman to explore what makes these visionaries tick - a selfless project in a field that is more often associated with big egos and self-importance.

"I think the reason why Tillman called it Film Stills of the Mind is because it's what each artist had in their subconscious. He spoke to them in depth about their passions, fears and fantasies, then he asked them to come and pose within the studio sets that he created of their fear or paranoia," says Mehnaz Tan, the gallery director at Elementa. "I think one tends to look at the artwork and forget about the artist that actually created the work and Tillman had a personal connection with them."

Some photos, like the piece entitled Wang Qingsong (pictured), put the artist inside his childhood fantasy. Wang is a lab-coated, possibly evil scientist in a hectic laboratory complete with steaming test tubes, a giant blackboard scribbled with equations and an oversized purple rabbit that seems to be the by-product of an experiment gone awry. It seems giddy and random, but there is an interactive video playing alongside the show that lets the artists, including Wang, explain the images.

"When I was in primary school, I used to day dream about being a scientist," says a male voice translating Wang's words into English. "But I had many feelings I wanted to express, and art became my favorite language of expression." Little snippets like these help fill in the gaps between Tillman's images and the deeper resonance this project had for the artists involved; without them, the photos remain glossily surreal without any connection to reality.

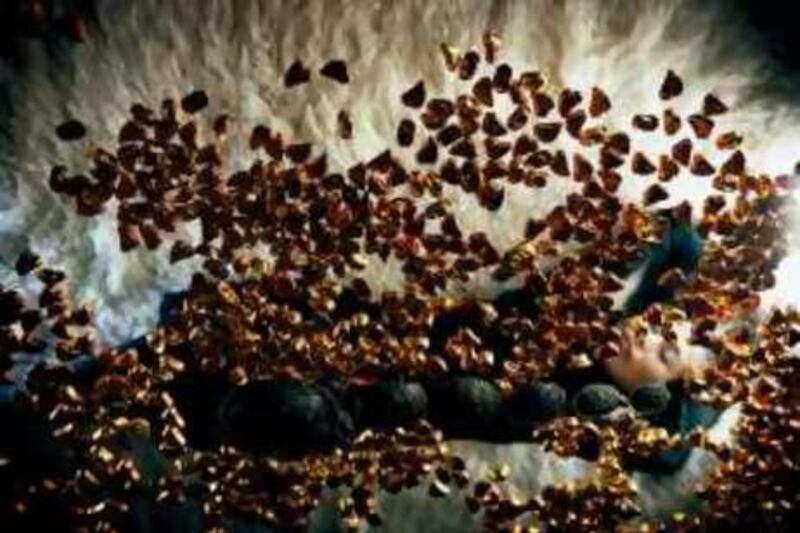

Another reason for working with the subconscious and memory emerges from reading Tillman's bio; the artist was diagnosed with bipolar disorder right before moving to China to work on this series. Though the images, like Zhou sailing the Huangpu in a urinal, are often funny and surreal, others are deeply haunting. In one photo, Yu Hong, a female artist who paints on everything from sculpted resin to silk, is lying on the bottom mattress of a corroded metal-frame bunk bed in a very plain dorm room with only a yellowing map on the wall for decoration. The photo itself is powerful; the angles of the furniture and Yu's physical positioning in the room evoke melancholy right away.

Sadly this scene bears a strong resemblance to Yu's reality. During the late 1960s, her entire family lived in one dorm room at the university where her father taught astrophysics. The image becomes haunting for the viewer as well when they imagine what it must have been like to grow up in that environment, to live in such a bare and tightly cramped space for the majority of one's childhood. In the video accompanying the show, she sounds detached from this memory, saying only, "the most remarkable memory I have of my childhood is the dorm room where I lived for years with my whole family". The visual recreation brings her childhood to life for us in a way that a simple sentence never could, exposing the realities of life during the years when China was closed to the world.

Tillman explores more hardships in his portrait of Sheng Qi. He photographs the artist's face in the dark with Sheng Qi's hand covering his forehead in a pose that highlights the absence of a missing little finger. The photo does not use a particular setting or recreated scene like the others do, and is more subtle than some of the other photographs on display. Jumping to conclusions about why this finger is missing can be misleading (no, it was not hacked off), the accompanying video explains that Sheng cut his own finger off as an act of protest during one of his performances around the time of the Tianamen Square uprising. The performance was an expression of the anger he felt when the Chinese government forcibly expelled residents from a longtime artist colony in Beijing. The image is arresting in its simple construction, and Tillman would have done well in this show to use this format more often.

Though their stories may be fascinating, these artists are not household names in this region. Still the show engages on a visual level with a pallette of rich reds, and also on an intellectual level challenging the viewer to decipher these strange scenarios. Scenarios such as Zhou cast adrift in his floating urinal. It's obvious from looking at the photo from close range that Zhou has been cut-and-pasted into the river. But the effect is still a powerful reference to Zhou's own work, which questions the absurdity and commercial nature of the Chinese contemporary art scene, something that surely would have interested Marcel Duchamp.

Even for those who are not familiar with Zhou's work, the image can be read on a different level. It is also a larger commentary on what it means to make art in a country that is changing so rapidly that it has come unmoored in the quick-flowing tide of modernisation. But the main point of the show remains the same - we are entering the dark though sometimes humorous recesses of the artists' subconsciouses, engaging with them on a very personal level and trying to make sense of it all (cue the castaway Zhou and mad scientist Wang).

But art, like life, is beautiful even when it doesn't make sense.

Hugo Tillman, Film Stills of the Mind at Elementa Gallery, Dubai, Gallerie 88 FZCO, LIU-K-05, Dubai Airport Free Zone. Until Dec 6. 04 299 0064, @email:www.galleryelementa.com

swolff@thenational.ae